Have you ever wondered why some people believe and some don’t?

Do we all make our choices for good reasons, or are we victims of misunderstandings and bad motives? Can we even make choices at all, or are our choices and beliefs predetermined by our genetics and upbringing?

What do psychology and neuroscience tell us about religious belief and how people come to believe in God?

On this page I have summarised what I have learnt from dozens of expert articles & papers, but can only scratch the surface of a complex topic.

Making decisions & forming opinions

Many factors are involved in making choices and forming beliefs. Some aspects are common to all of us, others are individual. Both our reason and our emotions are involved.

The amazing human brain

Our brains are made up of about 100 billion neurons (Ref 24), with about 100 trillion connections between them (synapses) forming a complex network. Electrical signals pass along the synapses and may or may not cause a neuron to “fire” and send signals along the synapses connected to it, and so information is transferred within the brain.

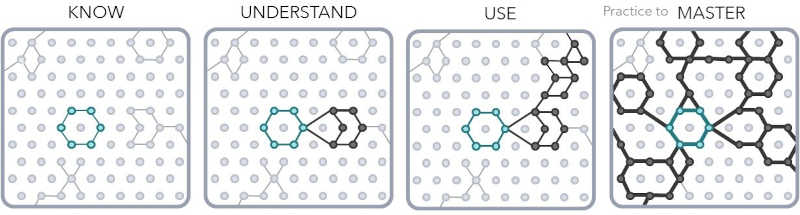

Information is stored in memory in our brains by new connections being formed between neurons. If we use the memory often, the connections become stronger, but if we don’t use the memory, the connections may weaken and disappear.

When we receive new information, our brain has to assimilate it into our memories and knowledge. If it fits with what we already know, our brains assimilate the new information, making new connections between the new and the old. But if the new information challenges what we already know or think, our brains have to do a little more work, to either accommodate the new information by changing our mental model, or rejecting it (Ref 11).

As we will see, our willingness and ability to change our minds will depend on how strongly we hold our current opinions and on a number of psychological factors.

So forming opinions and beliefs, and particularly changing our beliefs, depend on how we respond to the challenge of new ideas and information.

Different people, different minds

It’s an obvious truism that everyone’s different. So it’s no surprise to know that we all make decisions in slightly different ways.

Different people

Differences in age, character, temperament and mood can strongly influence decisions (Refs 1 & 2), for example:

- emotions such as fear, anger or regret

- past experience

- bias

- how relevant we perceive a matter to be

- how much we wish to involve others

- our cognitive capacity – affected by our age, memory, tiredness, skills and impairment.

Different brains

Our brains are very complex. Different, and sometimes contrary, processes in the brain can lead to different decisions.

- Perhaps the most important factors are two types of thinking – system 1, or intuitive thinking, which gives us fast, unconscious and often emotion driven responses, and system 2, or analytical thinking, which is slower and more deliberative (Refs 2 & 3). We’ll look at these more in a moment.

- In the brain there is a valuation network which provides us with information on risks and rewards, and a cognitive control network which helps us maintain an overall goal (Ref 4).

- Some parts of our brain are oriented toward survival and anger, others are more creative and compassionate (Ref 5).

- Some people are maximisers – they try to make the optimal decision – while others are satisficers – they try to make a decision that is “good enough” (Ref 6).

- Some people tend to choose the immediate and obvious gain, while others tend to seek the long term best outcome (Ref 6).

Different people may have different ones of these faculties more or less developed, which affects how we each make decisions.

Forming beliefs

Beliefs aren’t just religious or political opinions, but all opinions, in fact, everything that we think is true. So our beliefs are formed, at least in part, via processes discussed below.

We hold some beliefs with little conviction (e.g. whether our team will win a football game) but other beliefs can be held with great certainty (e.g. our love for our partner). Sometimes we can be certain about beliefs that are not in fact true.

Can we choose our beliefs?

Some people argue that we cannot choose our beliefs because our experiences and observations make us believe. For example if I see a red car, I am incapable of choosing to believe it is green, they say.

But beliefs aren’t always so clear. If someone asks me to lend them money and promises to pay it back, I can choose to trust them or not, based on how much I know them and other less tangible things. And I can certainly choose what information I read to help me form my beliefs – for example, choosing to read only one side of a political issue can lead to a strongly held belief that may in fact be wrong or doubtful.

Further, many athletes (and others) chose to visualise success so that they are more likely to achieve it. It seems that here, they have chosen what they want to believe and experience, and this makes it more likely that they will.

So it seems that we can sometimes make choices to believe or disbelieve, while at other times our beliefs are a simple response to what we have experienced.

Forming beliefs

Philosophers and psychologists say there are 6 basic sources of correct beliefs (Ref 17):

- Reason: using logical thought processes.

- Introspection: we can know what we are feeling in ways that no-one else can know.

- Perception: using our senses to observe the world around us. This includes our own everyday experiences plus the more rigorous scientific method.

- Testimony: what others tell us may be a basis for our opinions and beliefs if we trust their knowledge or expertise.

- Intuition: sometimes our experience leads us to accurately intuit something we come to believe.

- Memory: much of what we come to believe or think by the above methods is stored in our brains’ long term memory.

Cognitive biases

Unfortunately, we humans are all too prone to faulty thinking and intuitions (Ref 7) that may lead to incorrect beliefs through our emotions, fears, biases or inattention. For example:

- Loss aversion – most people fear loss more than they welcome success, so will generally make a conservative decision when considering gains, but will often take risks to avoid losses (Ref 3).

- Sunk cost fallacy – we are prone to continuing a cource of action we have invested time and resources into, even after it is shown to be wrong.

- Focus – we find it easier to consider immediate issues, harder to consider broader issues (e.g. some people’s response to climate change).

- Wishful thinking – being much more optimistic than is reasonable.

- Confirmation bias – focusing on ideas which we agree with and pushing aside ideas we don’t like. It takes the brain longer to process ideas we disagree with (Ref 33).

- Dunning-Kruger Effect – thinking we are more competent or knowledgable than we actually are.

- Extreme predictions: when we imagine the future we are likely to expect the worst of bad events and the best of good events (Ref 33).

The psychology of decisions

Most of us like to think we make our choices for very good and logical reasons. But psychologists have concluded that this is far from reality.

Emotions vs reason

Most choices involve a mix of emotions and reason, with psychologists generally concluding that emotions predominate in most choices (Ref 7), especially in religious, moral and political choices.

Our emotions affect our thinking in many ways (Ref 10):

- Some choices, for example the type of music we enjoy, may be the result of emotions or reasons we are hardly even aware of.

- If we are happy we can be more impulsive whereas if we feel sad we are likely to be more cautious.

- We all have our biases, and these will often affect our choices. For example, if we have had a bad experience with some food or situation or a person of a particular nationality, we may react negatively if we come across a similar situation again.

- If we are reading or listening to someone we dislike, this will often affect how we receive that information, regardless of the actual facts.

- Many of our decisions are based on what we feel will best help us achieve our goals, and this won’t always be a logical feeling.

Analytical & intuitive

Psychologists say we all have two different modes of thinking (Refs 2, 3 & 7) – analytical, which is slower, methodical and logical, and intuitive, which is faster and more likely to be emotional (though not always).

Analytic is good

Analytical thinking is best when we are facing a decision where we have all the information, have time to evaluate it and can work the issue through in a structured and systematic way. This is generally how science, the law, criminal investigations and historical study work.

Analytical thinking requires time and effort, and many decisions (e.g. deciding what to eat for dinner, choosing which shirt to wear) are not important enough for this.

Many people would benefit from being taught ways to better analyse information, e.g. do more formal analysis, train themselves to consider long term as well as short term outcomes, and encourage people to consider the opposite of their preferred choice (Ref 3).

Intuitive is good

But, perhaps surprisingly, intuitive thinking is more effective in some situations, and very necessary overall.

- Intuitive thinking is generally our first response, and many decisions are made this way. Some say all of our decisions are made intuitively, and analytical thinking is only used to rationalise our intuitive decisions (Ref 8).

- Emotions (which form part of intuitive thinking) have been found to be required to make good decisions (Ref 9), and people who use only analytical thinking make some choices poorly (Refs 12, 13). People with impaired emotions, and thus using predominantly analytical thinking, make worse decisions in some situations where judgment is required (Ref 14).

- Unconscious (intuitive) thinking is better than analytical thinking for complex tasks. Apparently analytical thinking struggles if the information is complex and there is no obvious methodology for reaching a decision, and unconscious thinking uses different brain process which organise the information better (Ref 2).

- Intuitive thinking is often better when risks are involved, because it tends to focus on the big picture rather than get bogged down in information (Ref 15).

- If we need to make a quick choice (for example, in an emergency), we may not have time for careful reasoning, which could leave us “frozen” and unable to choose in time.

Heuristics

The brain uses a number of heuristics (rules of thumb or thinking shortcuts) to help make better and faster intuitive decisions. Heuristics may include (Refs 1, 5, 7):

- recognise a pattern then act based on the most readily available memories of similar situations;

- choose what gives maximum utility (Ref 16) based on a quick assessment of outcomes;

- act on the first piece of information we receive;

- choose the most recognisable or familiar option;

- minimise negative emotion;

- make the decision that is easy to justify to oneself or others;

- anchoring and adjustment: start with an intuitive ballpark estimate and adjust until it feels satisfactory;

- reduce the likelihood of feeling regret later;

- evaluate just the most positive and negative aspects;

- if it works, trust it is right.

You might think these rules of thumb are not very reasonable, but studies show that using heuristics can give better results for less effort than trying to analyse everything (Ref 1).

For example, a study of doctors in a hospital emergency department showed that younger and less experienced doctors tended to make slower analytical decisions whereas the more experienced doctors made faster intuitive decisions using heuristics (Ref 3).

So these heuristics tend to give “good enough” answers most of the time, but can sometimes get things very wrong when the situation is very different to “normal”.

Both analytical & intuitive are necessary

Everyone uses a mix of analytical and intuitive thinking, with the mix varying in different circumstances. We all use intuitive thinking much of the time but some situations call on analytical thinking more than other situations do. Overall, some people are likely to use analytical thinking more often than some others are.

We may think that analytical is a better way to think than intuitive, but that isn’t always the case. Certainly, scientific study requires careful analytical thought (though even so, many scientists report having moments of intuitive inspiration verified later via careful analytical work). But as we have seen there are situations where intuitive may be “better”.

For optimum decision making, both intuitive and analytical thinking are necessary. “Any kind of serious complex thinking requires both analytical and intuitive thought” (Ref 2). It seems that good decision-making generally involves three steps:

- Initially, rapid intuitive thinking will likely reach a result using unconscious heuristics. This may be all that is required for many decisions.

- Reflection using analytical thinking may lead us to modify our decision, though often analytical thinking may only be used to rationalise the intuitive decision. It may take discipline to use analytical thinking to genuinely review our initial instinctive choice.

- Having done further review, intuitive/emotional thinking may still be required to actually make the choice rather than keep on thinking, or perhaps over-thinking.

We can conclude then that we make decisions using both emotions and reason in different ways depending on the circumstances.

Thinking better

We can improve our thinking by mindfulness – analysing our thought processes and recognising the possibility of bias (Ref 7). We can choose to value truth over comfort or self image. And we can train ourselves to use techniques to test our choices, for example, taking time to reflect on a decision, considering a wider range of options and reality-testing our assumptions.

Why people believe in God

So, how does belief in God fit with all this?

Reasons for belief

If you ask a thoughtful theist why they believe in God, you may be given one or more of several reasons, which fit in with the philosophers’ list of sources above.

- Reason: philosophical or other arguments that God exists (e.g. Why believe?).

- Introspection: feeling God has spoken to us or guided us in some way.

- Perception: observing or experiencing an apparently miraculous healing or seeing someone’s life change after coming to belief.

- Testimony: what we learn from others about their experiences of God, including the testimony of the scriptures or the teachings of parents, a priest or someone else we trust.

- Intuition: sometimes our experience (e.g. via heuristics) leads us to accurately intuit something we come to believe.

- Memory: memories of God’s apparent action in a person’s life may sustain faith long after the event has passed.

Not everyone who believes has, or can give, a clear reason why they believe. So it is interesting to examine the psychological reasons why people may believe in God.

Psychological reasons

Evolution?

Many cognitive scientists and psychologists believe that there are good evolutionary reasons why people believe in God.

The evolution of our brains

Our brains receive a vast amount of sense information, and they try to make sense what we see and hear. Psychologists have found that, from when we are very young, we interpret sense information in several ways (Ref 19):

- We tend to see order out of chaos. We often see patterns, even in apparently random events like the shape of clouds.

- We are prone to anthropomorphise our surroundings. The patterns we see are often human, like a face in a tree or even a pizza. We can easily think a shadow at night is a person.

- We often infer events are caused by agents rather than just random. It is easy to think a tree tapping on a window pane in the wind at night is a person. We can see why heuristics may lead to our brains working this way. For example, an ancient hunter who reacts to a rustle in the grass as if it is a lion, even if most times it isn’t, is more likely to survive to reproduce than one who doesn’t react but waits to see.

- We tend to infer teleology – natural things and events have a purpose, they are created for our use. Right from when we are very young, we experience our parents caring for us and our needs, and taking actions that affect the world around us for some purpose, and we extrapolate to think other events have a purpose and an agent behind them.

All of these thought processes, it is argued, make us more likely to believe that a God created us, cares for us and is active in events in our lives. Some neuroscientists have concluded that it is natural especially for children to believe in God (Ref 19).

Social evolution

Studies have shown that religious belief can assist human groups, whether families, tribes or nations, to prosper.

Many anthropologists conclude that belief in “big gods” (e.g. the classic monotheistic creator God who rewards “good” behaviour and punishes harmful practices such as theft, murder, etc) was necessary to provide the moral values and cooperation neccesary in large communities with complex cultures (Ref 18). Psychologist Ara Norenzayan: “If you believe in a monitoring God, even if no one is watching you, you still have to be pro-social because God is watching you.” (Ref 19)

So religion can assist in promoting altruism within the group. Religious people tend to be more prosocial and charitable. Psychologist Jonathan Haidt (Ref 20): “members of religious communities are simply better citizens. …. participation in a religious community has an effect that reins in selfishness and draws them out into community.”

But evolution is not enough

While all this may explain why religious beliefs have developed in almost every human culture, it doesn’t really help us understand why individual people believe today while others don’t. For that, we need to look elsewhere.

Psychological needs

Religious belief often satisfies psychological needs (Ref 29, 30) – belief in God helps people who …..

- feel deep uncertainty,

- need help coping with death or sufferning,

- want to see justice in the world,

- want to be accepted as a good person (Ref 31),

- are looking for answers to BIG questions of meaning & purpose (Ref 31),

- see eligion as a way to become a better person (Ref 31) – this need is discussed further below.

One eminent psychologist (Ref 32) suggests that religious belief satisfies all 16 basic human desires.

We can see these reasons in either a positive or a negative light. They may be seen as indicating a weakness in religious people, or they may be seen as showing how helpful religious belief is to most people.

Personal experience

Many people have a positive experience of religion, through their upbringing or through finding belief helps them.

I’ve compiled numerous stories of people finding new hope and purpose, release from addictions, healing, even communications from God via visions or other experiences. Such experiences are hard to deny or explain away, and most people accept them as a transformative experience.

Of course others find the opposite, which we’ll look at below.

Religion makes life better (generally)

We all know that religion can be a factor in socially harmful behaviours. So it may be a surprise to some to find that it is widely accepted among psychologists that religious people, on average, have better lives than non-religious (Ref 27).

Religious people tend to have better physical and mental health. They suffer less from depression and alcoholism. They are less prone to antisocial behaviour. Neuroscientist Andrew Newberg (Ref 21): “even minimal religious participation is correlated with enhancing longevity and personal health”.

In fact, religious practices such as prayer, meditation and ritual can actually change our brain structure in a beneficial way. Andrew Newberg says spiritual practices “enhance the neural functioning of the brain in ways that improve physical and emotional health”.

Meaning, purpose & authenticity

An Australian study of Christian conversion (Ref 22) concluded that the main reason people convert is a desire for “authenticity”, which the study describes as “a deep sense of yearning or wanting more ….. having a desire to live better or to become who they are”.

She explains how authenticity can lead to belief in God:

- Authenticity – embracing who we really are and being true to ourselves – is a key aspiration of our culture.

- Many people feel to be authentic is to be spiritual – they sense everything is connected by an underlying life force.

- To be truly themselves therefore, many people feel they need to look beyond themselves, to relationships with God and other people.

- So they conclude that to be a better person they need help from outside themselves.

- If they know Christians who they regard as authentic, this leads them to want the same, and to convert.

- This process generally leads to transformation – they exhibit healthy self image and altruistic relationships.

So a significant reason why some people believe in God is that they experience themseves, or see in others, socially and personally beneficial outcomes which lead them to believe God exists. Andrew Newberg again: “Our brains are set up in such a way that God and religion become among the most powerful tools for helping the brain do its thing—self-maintenance and self-transcendence.”

Cognitive biases

The cognitive biases listed above could all be applicable to religious belief – especially sunk cost fallacy, wishful thinking and confirmation bias.

Conversion

Conversion statistics

A worldwide study of people converting to different religions and belief systems (Ref 23) found that:

- Two thirds of those who changed beliefs spent a considerable time reading about the belief before they converted. Usually there came a “light bulb” moment when it seemed right to convert.

- Almost half chose to change beliefs after being turned off by the beliefs or behaviour of people in their former belief.

- More positively, many were seeking meaning or purpose in life, and were influenced by talking with adherents to the new belief system.

- The more committed the convert was to the new belief, the better their wellbeing.

- Almost half felt relectant to publically share their new beliefs and about a third felt they had sacrficed social connection by making the change.

A psychological analysis of conversion

One well accepted psychological analysis of the conversion process is by Rambo (Ref 22, p246), who identified 7 stages:

- Context. Factors that facilitate or hinder conversion.

- Crisis. May be personal, social, or both.

- Quest. Intentional activity on part of potential convert.

- Encounter. Recognition of other religious or spiritual option.

- Interaction. Extended engagement with new religious or spiritual option.

- Commitment. Identification with new religious or spiritual reality.

- Consequences. Transformation of beliefs, behaviors, or identity as result of new commitment.

This seems pretty reasonable, though I don’t suppose everyone follows the same model. But it does suggest that religious conversions are rarely sudden events, but come after considerable thought and interaction with believers (in person or in print/online).

The hand of God?

Psychologists, like other scientists, tend not to consider the possible supernatural actions of God in explaining religious belief, thought they do consider people’s belief that God has acted. Yet if God exists, his/her actions might be the most important cause of religious belief.

Why people don’t believe in God

Like belief, disbelief and unbelief can come from reason, psychological causes and personal experience.

Reasons for disbelief

- Reason: philosophical or other arguments that God doesn’t exist (e.g. the problem of evil, the hiddenness of God).

- Introspection: feeling disappointed that God hasn’t answered prayer or spoken to us.

- Perception: bad experiences with believers and/or the church, particularly spritual or sexual abuse, mistreatment of women or LGBTQI people, or hypocrisy.

- Testimony: what we learn from others about their bad experiences of religion plus the “testimonies” of respected non-believers.

- Intuition: experience (e.g. via heuristics) may leads people to intuit there is no God.

- Memory: memories of God’s apparent inaction in a person’s life may sustain disbelief long after the event has passed.

Psychological reasons

Psychologists have noted a number of factors that may lead people towards disbelief in God:

- Some say that analytical thinking tends to lead to atheism, but that view is now considered less likely (Ref 27). Nevertheless, it appears that some people slowly lose faith because they have difficulty integrating their spiritual feelings with analytical thinking (Ref 25).

- Cultural stagnation: people become more progressive, but their religious organizations are not (Ref 26).

- Religious or spiritual trauma or abuse, experienced themselves or in others (Ref 26).

- Suffering: not just the general propblem of evil, but suffering personally experienced, especially if taught that God would bless them (Ref 26).

- Chronically lonely people are less likely to believe in God (Ref 30).

- Overall, more intelligent or individual people are less likely to believe in God (Ref 30).

- Children of parents who identify as religious but don’t “walk the talk” are more likely to become atheists (Ref 28, 30).

Many of these reasons can be seen as causing cognitive dissonance, the feeling that beliefs no longer match experience.

Cognitive biases

The cognitive biases listed above could all also be applicable to religious disbelief – perhaps especially confirmation bias and Dunning Kruger Effect.

Conclusions

People use both intuitive and analytical thinking to arrive at their beliefs, including religious belief and disbelief. Believers are slightly more likely to think intuitively about religion.

While we generally like to think we are very reasonable in our beliefs, including religious beliefs, emotional & psychological needs, emotions, biases and personal experience can play a strong part in our choices, whether we are believers or atheists.

Some people are more likely to be more dependent on reason to arrive at their beliefs, but sometimes this is post hoc rationalisation. We can all learn to be be more cautious and reasonable in our conclusions. But sometimes intuitive thinking will be most suitable.

It may be that thinking about the existence of God is an example of where intuitive and analytical thinking are both equally useful.

The study of the psychology of religious belief and disbelief doesn’t generally consider the possible supernatural action of God in leading people towards belief, but this should surely be a factor to be considered in any account of belief. THerefore I suggest these psychological concierations need to be read with the understanding that they may miss something very important.

References

- Decision Making: Factors that Influence Decision Making, Heuristics Used, and Decision Outcomes, Cindy Dietrich (PhD student in Educational Psychology), 2010.

- Understanding the Dynamics of Decision-Making and Choice, Bryony Beresford and Tricia Sloper (Social Policy Research Unit, University of York), 2008.

- The Mechanics of Choice, Association for Psychological Science, 2011.

- Making Choices: How Your Brain Decides, Maia Szalavitz (neuroscience journalist), 2012.

- God and your brain. Cleveland.com, 2009.

- Decision-making, Wikipedia.

- Psychology of Choice: How Our Minds Navigate Decision-Making. Neurolaunch, 2024.

- Jonathan Haidt on Moral Psychology interview on Social Science Bites, 2012; Moral Psychology and the Misunderstanding of religion, Jonathon Haidt, and Social intuitionism in Wikipedia.

- Decisions Are Emotional, not Logical: The Neuroscience behind Decision Making, Jim Camp, 2012.

- The Psychology of Decision-Making: How We Make Choices. Psychreg, 2023

- How psychology can help you change someone’s mind. Fast Company, 2022.

- Thinking too much: introspection can reduce the quality of preferences and decisions, TD Wilson, JW Schooler, Department of Psychology, University of Virginia, 1991.

- Analytical thinking vs. religion, Connor Wood (PhD student in the science of religion), 2012..

- Neural substrates of decision making as measured with the Iowa Gambling Task in men with alexithymia, M Kano, M Ito, S Fukudo, Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine, 2011.

- Fast & slow decisions under risk: Intuition rather than deliberation drives advantageous choices. Aikaterini Voudouri, Michał Białek, Wim De Neys, Science Direct, 2024.

- Why and When Beliefs Change. Tali Sharot, Max Rollwage, Stephen Fleming, Sage Journals, 2022.

- Sources of knowledge: Stanford Encyclopedia, Oxford Academic and PressBooks.

- How “Big Gods” Make Us Play Nice. Connor Wood, Science on Religion, 2016.

- A reason to believe. Beth Azar, American Psychological Association, 2010.

- Is the Modern Mind Closing? Jonathan Haidt & Tim Keller on Youtube, 2017.

- How God Changes Your Brain. Andrew Newberg. Also Research Questions.

- Redeeming authenticity: an empirical study on the conversion to Christianity of previously unchurched Australians. Lynne Maree Taylor. PhD thesis, Flinders University, 2017. See also AUTHENTIC CONVERSION: becoming who we are created to be. Lynne Taylor, International Association for Missions Studies, 2016.

- Reasons behind religious conversiopns revealed by Leeds Beckett academics. Leeds Beckett University, 2016.

- I’ve seen various figures. Making and breaking connections in the brain. UCDavis Center for Neuroscience, 2020 says 120 billion. Wikipedia and many other sources say 86 billion.

- The Psychology of Christian Spirituality, Andy Tix, 2024.

- Why People Quit Religion—and How They Find Meaning Again. Greater Good Magazine, 2024.

- What do you believe? American Psychological Association, 2020.

- When and why do people become atheists? New study uncovers important predictors. Big Think, 2018.

- Five Causes of Belief in God. Nathan Heflick, American Psychological Association, 2012.

- The Belief in God: Why People Believe and Why They Don’t. Brett Mercier, Stephanie Kramer, Azim Shariff, ResearchGate, 2018.

- 5 Reasons Why People Believe in God. Thomas Swan, Owlcation, 2024.

- The psychology behind religious belief. Ohio State University, 2015.

- The surprising reason people change their minds. Claudia Hammond, BBC, 2018.

Main photo by TMS Sam. Diagram of brain assimilating new information is by Dr. Efrat Furst, and is used with her kind permission. Other photos (in order) by Anna Shvets, Kaboompics.com and Rosie Sun.

.

You may also like these

Feedback on this page

Comment on this topic or leave a note on the Guest book to let me know you’ve visited.