We are all conscious when we are awake. But what is consciousness and how does our brain make us conscious? This is one of the most important and difficult questions today for science, religion and ethics.

It is difficult to explain scientifically what we feel and experience, but neuroscience and philosophy are beginning to develop new approaches to consciousness.

If we only consider the physical, as science does, then we may never be able to measure an intangible like consciousness. If we believe the physical is all there is, the problem is harder.

So it isn’t surprising that other viewpoints have been put forward, that our minds and consciousness are somehow more than physical and yet quite real.

Our human experience

We all know what it feels like to be us

, but we know very little of what it feels like to be someone else. We all feel there is some distinct being that is us, even though the particles that make up our bodies and brains are constantly being replaced by new particles. We all have memories of our past, even if we forget more than we remember.

And each of us knows what it feels like when we taste coffee or listen to Bob Dylan or see a certain special person of the opposite (generally) sex. But we don’t know what those same things feel like to others, and we can be fairly sure that although the coffee, the Dylan song or the person may be the same, the experience may be very different. For example, I dislike coffee and I like Bob Dylan’s music, but many of you may feel the opposite.

And our brains are active, introspectively, most of the time we are awake. “What are they thinking about me? I wish I could remember her name. Do I look silly with this haircut? Now what was I going to do next?” etc.

This is what it is like for us to be human. We are conscious of ourselves, and it seems like we look out on a world where other people inhabit their bodies and look out at us.

Mind and consciousness

Philosophers and neuroscientists find it very hard to define mind and consciousness. We experience them, in a sense we are them, yet in another sense thay do not exist in any tangible way. Scientific definitions tend to focus on neuronal activity in the brain, but it seems like we are more than that. Perhaps we can simply say that consciousness is self awareness, or the feeling that accompanies brain activity (e.g. the pain that accompanies the brain activity leading to the automatic reaction to remove one’s hand from a hot stove), and mind is the sum of the brain’s conscious processes.

But there are many questions we may ask. What is self? Is the mind or consciousness simply a way of describing brain activity, or are they something more?

The story from scientific materialism

The majority of brain scientists are materialists or ‘physicalists’ (i.e. they believe that everything is material or physical, or can be explained by the physical), or at least they make materialistic assumptions when they do their science (this is known as ‘methodological naturalism’).

They point, for example, to the deterioration in the mind and consciousness as the brain deteriorates, and argue that mind and consciousness arise from brain activity and are not separate from it. Hence mind and consciousness are described as “emergent” properties of brain activity, and thus everything can be explained by physics.

“There’s considerable evidence that the unified self is a fiction – that the mind is a congeries of parts acting asynchronously, and that it is only an illusion that there is a president in the Oval Office of the brain who oversees the activity of everything.

Steven Pinker

” … as a scientist, I simply cannot accept that there is any part of the physical universe that cannot be understood and explained by the methods of science.”

James Trefil

Problems with the materialist approach

There seem to be three main problems for a scientist who is a materialist:

1. Material vs immaterial

It is hard to explain something immaterial like our consciousness in purely materialistic terms – i.e. in terms of matter and space. How can a physical brain produce subjective experience?

“The mind … remains a mystery. It has no mass, no volume and no shape, and it cannot be measured in space and time. Yet is is … real ….”

Neuroscientist Mario Beauregard

“You’ve got a brain made of billions of neurons, and all those neurons are doing is shunting electrical impulses and little molecules of chemicals here and there, back and forth. That’s all they’re doing. How can that be, or give rise to, or be responsible for …. the experience of [colour]?”

Susan Blackmore

2. Contrary to experience?

Materialism cannot explain all we experience. From the inside, it feels like we are more than the materialist explanation allows for. Should we reject what we experience just because a materialist scientist cannot explain it? Even the scientist has difficulty maintain the materialistic view in real life.

“How can objective things like brain cells produce subjective experiences like the feeling that ‘I’ am striding through the grass? …. The objective world out there, and the subjective experiences in here, seem to be totally different kinds of things. Asking how one produces the other seems to be nonsense. The intractability of this problem suggests to me that we are making a fundamental mistake in the way we think about consciousness

Susan Blackmore

“There is an implausibility in those who seek to reduce parts of [our] experience to the status of epiphenomenal, an implausibility repeatedly exemplified by our inability outside our studies to live other than as people endowed with free agency and reason.”

John Polkinghorne

3. The ‘hard’ problem

Materialist science can explain many brain functions – how the brain reacts to stimuli, how it categorises information, how it controls our behaviour, etc. But these functions could all be carried out without our consciousness, and often are. So why does the brain generate our conscious experience?

If there was more to “us” than our physical brain and body, then we could understand that conscious experience relates to that “us”, but if the material brain is all of “us” then consciousness seems unnecessary and unlikely. This question, commonly associated with Aussie philosopher David Chalmers, is sometimes called the “hard problem”.

And pretty much everyone admits it is indeed hard.

Alternative views

There seem to be three ways one could try to resolve the mystery of consciousness:

Materialism

Our self is an illusion. We feel as if we are a unified being living inside our bodies, but we are not (see the Steve Pinker quote above). Science will one day explain it all.

“You, your joys and your sorrows, your memories and your ambitions, your sense of personal identity and free will, are in fact no more than the behaviour of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules.”

Francis Crick

“The human brain is a machine which alone accounts for all our actions, our most private thoughts, our beliefs… All our actions are products of the activity of our brains. It makes no sense (in scientific terms) to try to distinguish sharply between acts that result from conscious attention and those that result from our reflexes or are caused by disease or damage to the brain.”

Colin Blakemore, neuroscientist.

Dualism

The view that there is mind or self above and beyond the brain (a viewpoint which cannot be proven, or disproven, scientifically, but which can be argued philosophically), is called dualism. Dualism tends to be scorned by most scientists because it cannot be demonstrated by science (although neither can it be refuted), and is thus to some degree an article of faith. But equally, the belief that dualism isn’t true is also an article of faith.

“Although dualism cannot be disproved, the role of science is to proceed on the assumption that it is wrong and see how much progress can be made.”

Alwyn Scott.

Many christians would be dualists, believing that consciousness was created in us by God, and it is this that makes us ‘higher’ than animals.

Non materialistic monism

Philosopher David Chalmers suggests science will only resolve the question if it ceases to be materialistic, and adopts a new approach. Matter is not all there is – consciousness or experience is a fundamental fact of the universe just as magnetism and gravity are. John Polkinghorne also argues that this is the most logical explanation of all the evidence.

” …. the mind cannot be reduced to the brain …”

Todd Feinberg

Evaluating these viewpoints

Philosophers have developed arguments that support dualism, just as they have developed counter arguments. Scientific research is unclear on this matter. There are experiments that can be seen as supporting some form of dualism, and some which suggest we don’t have conscious control of our actions (see Free will). But it would seem that after a period where a materialistic approach ruled, there are more scientists and philsophers finding evidence supporting something like dualism and freewill.

In evaluating these two views, we come across a logical problem. Scientists tend to assume that science can (in principle) explain everything in the universe (an assumption which is not demonstrable by science, as can be seen from the quotes from Alwyn Scott and James Trefil, above), then argue that since dualism cannot be proven by science it is not respectable.

So it is a circular argument. The materialist belief is also an assumption, or even an act of faith. Nevertheless, science cannot do other than study what it can study. But we may best remain open-minded about those areas which science cannot study, and not simply assume them to be non-existent.

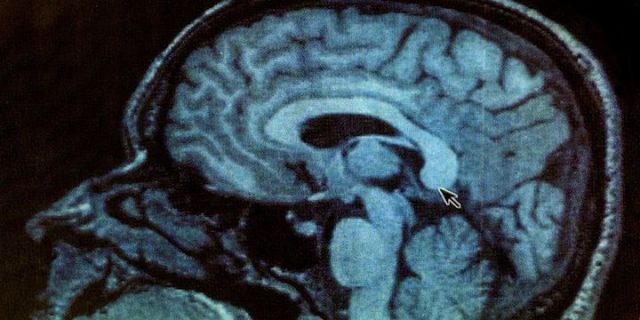

Photo Credit: Mikey G Ottawa via Compfight cc

Feedback on this page

Photo Credit: Mikey G Ottawa via Compfight cc. Page last updated 19 March 2016.

Comment on this topic or leave a note on the Guest book to let me know you’ve visited.

Read more

On this website

- Do humans have free will? – a brief examination of a complex philosophical and scientific question.

- Are our brains like computers? – how our amazing brains work.

- How do we know right and wrong? – are ethical statements objectively true, and how can we know?

In books

- Brain Wars. Mario Beauregard

- Are we Unique? James Trefil

- Stairway to the Mind. Alwyn Scott

- Altered Egos. Todd Feinberg

Online

- The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, with articles on many topics related to mind, consciousness and freewill.

- Writings of David Chalmers, Professor of Philosophy at the Australian National University and philosophy of mind editor for the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Facing Up to the Problem of Consciousness. Also of interest are Chalmers’ book, The Conscious Mind: In Search of a Fundamental Theory and a response from an alternative view in A Materialist response to David Chalmers’ The Conscious Mind by Paul Raymore.

- Hard problem of consciousness, Neuroscience, Mind, Consciousness” and Free will, in Wikipedia.

- Interview with Susan Blackmore in Third Way magazine.

- Victor Reppert on consciousness: Truncated Thought part II and I am not a selfplex.

- Mind and Consciousness in “The Big View”.

- The Mind-Brain Problem, the late John Beloff.