This page in brief ….

Our brains are indeed amazing, a powerful memory, body-controller and calculator packed into a small space. And while they share some properties and functions with computers, they are in fact very different. They are much more complex than computers in their structure and how they operate. So far, no computer can pass a simple test to show it thinks like a brain. And the brain can repair itself and re-structure and re-program itself.

Then there is the mystery of how we are conscious (something computers don’t appear to be) and how we appear to have the freedom to make choices (which computers definitely don’t have).

How the brain works

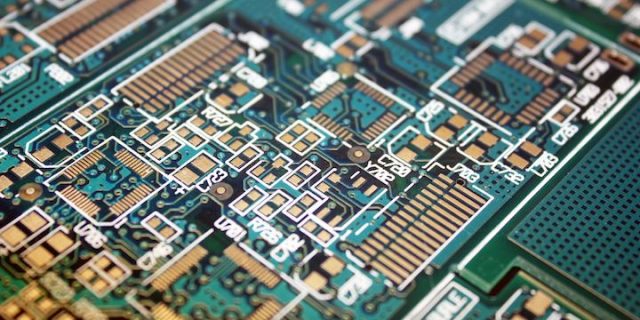

Research continues to discover how amazing our brains are. A brain weighs about 1.5 kg, yet has more connections and more “messages” than the phone systems for the entire planet. Brains work by intricate electrical and chemical processes and are far more complex, and different in their operation, than computers. For example:

- Signals travel around electrical circuits in a computer, but in the brain the transmission of information is via a much more complex combination of electrical and chemical actions. The human brain has about 100 billion neurons connected by more than 100 trillion synapses. Neurons are basically electrical on/off switches which work similarly to the miniaturised transistors in computer chips. Information is passed between neurons via chemical synapses, which release neurotransmitters which act on another neuron.

- Most neurons are connected via synapses to several thousand other neurons, making the brain’s circuitry exceptionally complex.

- A computer would generally store all the details about a picture of a car in one location, whereas the human brain may store the colour in one location, its sound in another and its movement elsewhere again.

- Computers are programmed (though they can be programmed to learn by experience), whereas brains learn by experience and thus, in a sense program themselves, and are capable of re-programming themselves.

Thus brains are like computers in some ways, and a computer can be programmed to act like a brain, but they operate by very different processes.

The Turing test

A computer can be programmed to act like a brain (artificial intelligence), so how can we tell the difference? Can we conclude that computers can think? Could computers have consciousness and freewill?

Mathematician Alan Turing considered these questions and proposed a test for whether a computer can think. A computer and a person (known simply as X and Y) are in one room and a questioner is in another. The questioner can ask any question she chooses, directed to either X or Y. If the computer passes the Turing test, it is able to give answers that cannot be distinguished from the answers of a human, so the questioner is unable to identify which of X and Y is the computer and which is the human. One could say that the computer is able to think like a human being.

Not everyone agrees with Turing, and so far, despite the amazing growth in capability of computers (even including their ability to defeat the world chess champion), they cannot pass the Turing test with any consistency. So we may conclude that, at present at least, computers cannot think.

Neuroplasticity

It used to be thought that, while cells in all other parts of our bodies can regenerate, the brain’s cells cannot. But this has been found to be wrong – the brain is quite ‘plastic’, and cells can be regenerated or re-programmed to accomplish new tasks.

If part of our brain is damaged, another part can often take up the load. If a part of our body is damaged and the part of the brain that controls it is no longer needed, it can be redirected to other tasks. If we start to learn new skills or focus on some aspect of life or knowledge, our brain can adjust, forming new linkages, pathways and maps to improve our abilities or recover lost abilities. Sometimes these changes require disciplined training, but sometimes they happen quite naturally.

The other side of the coin is that if we stop using parts of our brain by allowing our thoughts and habits to remain in familiar paths, those parts of our brain can become less effective. As we age, this can become a particular problem.

Keeping our brains fit

So like a computer, faults in our brains can be repaired. But unlike a computer, the brain repairs itself – generally we have to help it along but the brain is doing the hard work.

So exercise programs have been developed to recover lost abilities, slow the onset of aging, repair damaged areas, recover from strokes, assist people suffering from depression or cerebral palsy, and improve our abilities, brain functioning, memory and even intelligence. Training can also improve noral functioning, but making real physical changes to our brains – adding brain power by adding extra neurones and increasing the connections between neurones.

Neuroplasticity and God

The new discoveries about neuroplasticity also affect religious belief. Religious and spiritual practices such as prayer and meditation change the structure of our brains and lead to physical and mental health benefits such as lower blood pressure, lower heart rates, decreased anxiety, and decreased depression. And what we focus our thoughts on can change our brains too. Neuroscientist Andrew Newberg:

The more you focus on something — whether that’s math or auto racing or football or God — the more that becomes your reality, the more it becomes written into the neural connections of your brain.

Mind and consciousness

Philosophers and neuroscientists find it very hard to define mind and consciousness. We experience them, in a sense we are them, yet in another sense they do not exist in any tangible way. Scientific definitions tend to focus on neuronal activity in the brain, but it seems like we are more than that. For now, we can simply say that consciousness is self awareness, or the feeling that accompanies brain activity (e.g. the pain that accompanies the brain activity leading to the automatic reaction to remove one’s hand from a hot stove) and mind is the sum of the brain’s conscious processes.

There are many questions we may ask. What is self? Is the mind or consciousness simply a way of describing brain activity, or are they something more?

Delving into these questions gets into deep areas of neuroscience and philosophy, which are beyond our purpose here – if you’re interested, check out The mystery of consciousness. But the views we hold about mind and consciousness can affect our behaviour and our views about life, meaning, God, ethics and the value of human life.

Free will?

One important question which arises out of considering the brain, mind, consciousness and self, is that of freewill. Are our actions fully determined by these brain processes, as is the case with computers? Do our brain processes control us, or do we control them? Do “we” exist separately from our brain processes? Are consciousness, choice and personality real?

Such questions are hotly debated. Many academics these days are determinists, that is, they believe we cannot initiate new thoughts, because there is no “self” outside the brain to initiate anything. Our brains are “us”. Thus every thought is in fact determined by electro-chemical processes and external stimuli, and we have no real freedom of choice, that is, the possibility of changing the flow of events. They point to experiments which appear to show that the brain processes which cause a physical action (say, raising one’s arm) begin in the subconscious, thus suggesting that the conscious mind does not originate the process. This would appear to show that our actions are determined, and we have no real choice about them. However others have raised doubts about the validity of these experiments. (For a little more detail, see Free will.)

Conclusions

So it appears our brains are not very much like computers at all. Computers operate differently, they cannot self repair and adjust as our brains can, and most people would say that they lack minds, consciousness and freewill. But if you believe humans also lack these …..

How does this change if there is a God?

Our conclusions about consciousness and free will probably be determined by our assumptions:

- If we assume the physical is all there is, we will think the only correct explanations come from science. We will conclude that our minds and consciousness are the product of our brains alone, and we are therefore controlled by our brain processes. Thus we have no genuine free choice, we cannot be held morally responsible for our actions, and we cannot regard humans as anything more than an intelligent animal.

- If we assume we can trust our experience of being ourselves we may conclude there is a non-physical self that science cannot measure. It feels like we have free will, and we will conclude that indeed we do, and we can therefore be held morally responsible. Humans are thus more than just intelligent animals. This view is often, though not always, associated with a belief in God.

Those who trust neuroscience to address questions of metaphysics will probably feel that the latest discoveries add to the reasons not to believe that God exists. But those who think neuroscience should stick to what it can measure (not what it can’t), and instead trust their own experience of being human, may conclude that, if the choice is between no God and no free will, or God and free will, they will choose the latter.

Quotes

“You, your joys and your sorrows, your memories and your ambitions, your sense of personal identity and free will, are in fact no more than the behaviour of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules.” Francis Crick, The Astonishing Hypothesis, quoted in Are we unique? by James Trefil.

Trefil comments: “[Crick] is obviously worried that if people do not accept the Astonishing Hypothesis, they will be driven to accept religion and the existence of the soul. …. I’m not sure this is true.”

“Although dualism cannot be disproved, the role of science is to proceed on the assumption that it is wrong and see how much progress can be made.” Alwyn Scott, Stairway to the mind.

” …. the mind cannot be reduced to the brain …” Todd Feinberg, Altered Egos

” … as a scientist, I simply cannot accept that there is any part of the physical universe that cannot be understood and explained by the methods of science.” James Trefil, Are we unique?

“There is an implausibility in those who seek to reduce parts of [our] experience to the status of epiphenomenal, an implausibility repeatedly exemplified by our inability outside our studies to live other than as people endowed with free agency and reason.” John Polkinghorne

“The human brain is a machine which alone accounts for all our actions, our most private thoughts, our beliefs… All our actions are products of the activity of our brains. It makes no sense (in scientific terms) to try to distinguish sharply between acts that result from conscious attention and those that result from our reflexes or are caused by disease or damage to the brain.” Colin Blakemore, neuroscientist.

Photo: MorgueFile.

Feedback on this page

Comment on this topic or leave a note on the Guest book to let me know you’ve visited.

Read more about consciousness, ethics and freewill on this website:

- Free will – a brief examination of a complex philosophical and scientific question.

- The mystery of consciousness – what is consciousness and how does our brain make us conscious?

- How do we know right and wrong? – are ethical statements objectively true, and how can we know?

Further reading – books

- The brain that changes itself. Norman Doidge

- Brain wars. Mario Beauregard

- Are we Unique? James Trefil

- Stairway to the Mind. Alwyn Scott

- Altered Egos. Todd Feinberg

- The Modular Brain. Richard Restak

- Brain Story. Susan Greenfield

- Creation: Life and how to make it. Steve Grand

- Freedom Evolves. Daniel Dennett

- Mind and Cosmos. Thomas Nagel

Further reading – on the web

- The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, with articles on many topics related to mind, consciousness and freewill.

- Writings of David Chalmers, Professor of Philosophy at the Australian National University and philosophy of mind editor for the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Also of interest are Chalmers’ book, The Conscious Mind: In Search of a Fundamental Theory and a response from an alternative view in A Materialist response to David Chalmers’ The Conscious Mind by Paul Raymore.

- Understanding how the brain works, Dr Glen Johnson.

- Slide show: How your brain works, Mayo Clinic.

- Neuroscientist Andy Newberg on belief and the brain

- Mind and Consciousness in “The Big View”.

- A summary of the work of Wilder Penfield in Wikipedia and a summary of observations mentioned above in The Illusion of Conscious Will by Daniel M Wegner.

- Freewill and moral responsibility, edited by John Fisher, especially Neurobiology, Neuroimaging and Free Will by Walter Glannon.

- The Oxford Handbook of Free Will, edited by Robert Kane.

- Neuroscience, Mind, Consciousness” and Free will, in Wikipedia.

- The Mind-Brain Problem, the late John Beloff.

- Wikipedia and The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy on the Turing test.