Christopher Hitchens has famously claimed that religion poisons everything. Is this rhetoric, or do the facts bear him out? On this page I examine the good, the bad and the ugly of both belief and unbelief.

To do this I look at a wide variety of evidence, which is listed at the end. I conclude that religion is only one of many factors that affect happiness and wellbeing. When religion, especially christianity, is practiced by sincere believers it is beneficial to both the believer and humanity generally, but when used by powerful forces to further their own ends, religion can be very harmful. Unbelief has the same problems, though not so intensely.

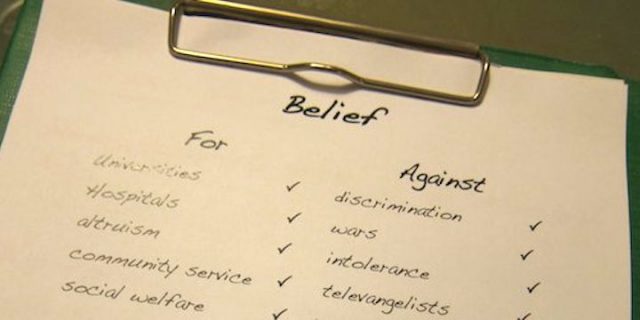

Religion: the good ….

Theism has been a significant part of most cultures throughout time. The three great monotheistic religions (Christianity, Judaism and Islam) have contributed much to the cultures of the societies that have embraced them.

High aspirations

At their best, they have set high aspirations for humankind, with advanced ethical codes and a strong emphasis on unselfishness, altruism and concern for others, especially the less fortunate. Much of our legal systems come from the Judaeo-christian tradition, and there is a similar connection in Muslim countries. The monotheistic religions have inspired great works of art, architecture, literature and music, and have often sponsored learning. It is arguable that the growth of science in the western world was assisted by the christian belief in an orderly creation by God.

Historical author (and non-believer) Tom Holland has argued that the ethics of the world before christianity was very different to now, with many things we take for granted not being features of the ancient world. His study of ancient Greek and Roman culture showed violence, brutality and disregard of human life on a massive scale – expressed in things like widespread slavery (and abuse of slaves), sexual exploitation, and brutality and disrespect for life of non-Romans.

But, he says, christianity taught us that all people were equal in the sight of God. This led to sexual exploitation and brutality becoming less acceptable, and a radical care for others, including the weak, the needy, the vulnerable and the exploited. Some time down the track it led to opposition to slavery (which was generally acceptable in the ancient world). Paradoxically, christians were largely responsible for the separation of church (religion) and state (secular).

Holland points out the darker side of christianity, but adds that this was when the christians didn’t live up to the ethical standards they had brought into society.

Community care & concern

Christians initiated universities, schools, hospitals (plus the Red Cross, which led to the Islamic Red Crescent) and trade unions, and have a long history of caring for the disadvantaged. For example, it was primarily christians who opposed the slave trade and child labour in Great Britain. This continues to the present day, with the work of social welfare agencies like the Salvation Army in western countries, and christians still undertaking pioneering medical and aid work in many third world countries. Christians have been shown to be good community volunteers and generous to charities in western societies.

Personally

On a personal level, christians (and other believers, presumably) have higher levels of happiness, wellbeing and physical and mental health than other members of our society (see what makes people happy? and faith and wellbeing). Most believers would claim that their faith has helped them personally also (see box: tales from two faiths), among other things, giving them a sense of purpose and direction in life, inner peace, and (for some religions) freedom from guilt via God’s forgiveness. With more than half of the world’s population believing in monotheistic religions, this is an impressive number of satisfied customers!

Tales from two faiths

A supreme lightness of being

B is a typical Aussie bloke who converted to Islam about six years ago, after deciding it was true. “It was like a weight that was lifted from my shoulders”, he says, “Now I know why I am here. Islam is compassionate, it’s merciful and it’s got everything I need in a religion.” His conversion led to a gradual loss of many friendships, but he says he now has ‘a supreme lightness of being’.

It lasts

The first two decades of J’s life were not easy – a violent and broken home, raped as a child and as a teenager, she left home at 15 and lived with a number of men, many of them violent, and she became addicted to drugs. Pregnant and abandoned by the father, she went to a church to get help. She decided to become a christian. Through a number of sessions of deep prayer, J has received healing from God from awful memories and low self esteem. Horrific nightmares have ceased, and she is now happily married to a christian man. When asked if her story could be included in a book, J replied “Yes. And tell them it lasts.” (Read this story in slightly greater detail at It lasts!.)

…. the bad and the ugly

On the other hand, religion has led to some terrible outcomes:

Intolerance

Religious differences can lead to intolerance, discrimination and persecution – for example witch hunts in medieval Britain and in the US, discrimination against gays (hopefully now on the wane), and Muslim repression of women and dissidents.

Killing

Religion is also implicated in much war and killing, from the crusades and the mistreatment – murder, rape, subjugation, enslavement and sometimes genocide – of indigenous peoples in North and South America, Australia, India and elsewhere, through the Irish Republican struggles, to the Sudan civil war, the Israeli-Palestinian fighting, religious based fighting in Sri Lanka and Kashmir, the current threat of Islamic terrorism and the recent so-called war on terror. It is difficult to disentangle religious, political, national and other causes in all these situations – terrorism and war have been shown to be predominantly caused by political grievances (see Does religion cause terrorism? and Does religion cause war?), but religion is still sometimes implicated.

Repression

Religious leaders have often supported repressive regimes – for example, the christian church’s support for the inequalities of European feudal society, the acquiescence of many German christians to the atrocities of the Holocaust (though there were many notable, and brave, exceptions), apartheid in South Africa (again there were christians who helped bring down apartheid), and the repressive nature of Muslim governments in Saudi Arabia, Iran and elsewhere (for example, the harsh repression of women and dissenters).

The Hindu religion is the direct cause of the discriminatory caste system in India, which inflicts great suffering on the Dalit caste. It also seems to condone inequality and corruption in some countries.

Slavery was conducted in so-called christian countries, and still occurs in some Muslim areas of Africa.

It has been claimed that the church opposed the growth of science in the middle ages and since, but the historians tell us this was only occasional, and that generally the church supported scientific research – it helped establish universities, and many of the first ‘scientists’ were priests.

But wait, there’s more!

Religion has brought us US televangelists, Mormon doorknockers, paedophile priests, Ned Flanders, suicide bombers, harsh treatment of children in Catholic schools and institutions, female circumcision, sacred cows, hypocrites and wowsers. Unbelievers, from Freud and Lenin to the present day, have argued that religion keeps people in slavery.

Making an assessment

This double-edged heritage of religion raises some difficult questions. Many people would argue that the net effect of religion on human culture has been decidedly negative, and are strongly anti-theistic as a result. However others, even non-believers, see much good flowing from christian belief.

An objective assessment is complicated by conflicting factors:

- Not all who act in the name of a religion are actual believers. If someone blatantly disobeys the teachings of a religion while holding some position within the organised structure of that religion, can they be considered to be ‘true believers’? For example, for many centuries, the christian church was the strongest power in Europe, and thus attracted many people for wrong motives, who behaved in a manner far from the teachings of Jesus.

- “Believer” is not the only category to which a person may belong – they also belong to a nation, may be part of a government, or involved in commerce, etc. To which category should the blame be assigned?

- “Religion” is too general a term – not all religions are the same or homogeneous. For example Christianity appears to be (overall) more benign today than Islam, and less repressive than it sometimes was in the past.

It seems true that when christians follow the teachings of Jesus, the result in their lives is good and they are more inclined to act altruistically. The problems seem to come when religion is allied with, or even co-opted by, political power.

Nobel Prize winning Physicist and atheist Stephen Weinberg said, with some justification: “for good people to do evil things, that takes religion.” But it also seems true that “for ordinary people to do altruistic things takes religion”. CS Lewis summed up this double-edged nature of christian belief this way: “when Christianity does not make a man very much better, it makes him very much worse”

CS Lewis’ view is supported by scientific studies of religion. A study reported in Science on Religion found that believers with a personal “intrinsic” religiosity are more compassionate to others, whereas those who follow their religion for less personal reasons (such as social conformity) are more likely to be distrusting and hostile towards outsiders. The report concluded:

This imbalanced dynamic ensures that religion’s role in human affairs will continue to be as complicated and problematic as it always has been. The only difference is that now we might remove some of the blame from “religion” and put it where it belongs: on the laps of religious people who don’t understand, or willfully ignore, the ethical teachings of the traditions they so earnestly espouse.

Perhaps the last word should go to an atheist journalist who sees christianity as a major force of freedom and good in Africa, despite his belief that it is not true.

Non-belief: the good ….

Changes in the world

Following the gradual demise of theism in the west (possibly only 50-100 years or so ago), there have been both gains and losses. On the positive side, in this period we have seen:

- an awareness of global inequalities, and the first steps in remedying this;

- determined efforts to reduce racism and the persecution of minority groups such as gays;

- increased opportunities for women as discrimination against them has ceased, or at least been reduced significantly;

- identification of paedophilia and abuse of children as major problems, and positive steps to reduce them;

- greater awareness of the dangers of environmental degradation and significant improvements;

- the gradual spread of democracy, and greater freedoms for citizens in many countries; and

- growing anti-war sentiment in many countries.

These gains cannot all be claimed by the anti-theists – many theists have been involved also. But one could, perhaps, say fairly that these movements have had a significant secular basis.

Personally

On the personal level, many people rejoice to have been freed from what they see as the yoke of religion, superstition and dogma (see box: two satisfied sceptics), although others have found scepticism to be empty, and faith to be more satisfying.

Two satisfied sceptics

No religion, but a spiritual person

X had an atheist father and little contact with religion. Christian friends tried to convert her, but it didn’t last, and she is now an atheist. She is strongly motivated by compassion for others, and has found help in the writings of the Dalai Lama. “I want to do good in the world and I think that I can do far more without a binding set of commandments saying what is right and what is wrong” she says. “I have no religion, but I am a spiritual person. I believe that if a person is capable of doing a good thing in the world, then she has a responsibility to do so. No god tells me to do this, only my heart.”

Profiting from independence

S was a committed ‘fundamentalist’ christian until she went to college, where she studied the Bible and decided it wasn’t true. She is now highly critical of the church in the US, especially its attitude to women and its money seeking. She rarely misses her former faith. “It sometimes saddens me when I need something to comfort me, and remember that I once had my faith, but in the end I always profit from my independence. But life is so-much more real, and fulfilling, when you live it for yourself, and not some imaginary, unseen patriarch.”

…. the bad and the ugly

However, secular societies have also been responsible for some less beneficial social outcomes:

Killing

Some of the worst examples of genocide, and all of the largest numbers of deaths, have come from secular (basically non-theistic, and often avowedly atheistic) cultures. Hitler’s Nazism killed 6 million Jews in the Holocaust, and more than 50 million in total in World War 2, Stalin’s communist regime is generally considered to have murdered more than 20 million people, with some estimates being far higher, and Mao Zedong’s regime in China may have been responsible for 40 million deaths. Add over 10 million in the Russian and Chinese civil wars, and the atrocities of the Pol Pot regime in Cambodia, and the twentieth century cannot be considered a triumph for secularism.

Intolerance

Many of the same countries can be used as examples of intolerance, hypocrisy, persecution, inequality, and loss of human rights. Humanists will argue that the excesses of communism and other totalitarian systems are not representative of their beliefs, which is true. It is difficult to disentangle the impacts of atheism and other beliefs – the same dilemma we discussed when considering theism. Nevertheless, these facts must still be considered in assessing secularism.

Western imperialism

The US exercises a strong military, economic and cultural influence over the entire world, which is resented by large numbers of people worldwide. It has led to warfare and other interference in other countries, trade and economic practices that entrench American wealth at the expense of poorer countries, and threats to the culture of many countries as McDonalds, Coca Cola, Microsoft, US music, films, TV and sports backed by clever advertising impact on impressionable people, particularly youth.

Shallow values

Along with this US ‘cultural imperialism’ has come increasingly shallow values, based on consumerism, image, personal financial gain and short term vision. Teens can easily be overly influenced by image, and sexual exploitation in advertising and the media – girls can grow up obsessed by body image.

Ethics and integrity

Many companies have a poor record of integrity – for example, a recent Royal Commission (judicial investigation) of banking in Australia revealed questionable ethics and illegalities by many involved). And governments in democratic countries are increasingly accused of deliberate deception, dishonesty, self interest and corruption.

Loss of meaning

Confidence is fast fading that western capitalism and humanism can deliver happiness and purpose in life, and many feel they are responsible for a loss of community values and ethics, youth suicide, family breakdowns, drug addiction and crime (see box: What the world needs now ….).

Studies show that suicide is higher in advanced secular western countries. Non-religious people have lower physical and mental health, including higher levels of worry, stress, depression, suicide and destructive behaviour, and they are less likely to contribute to society through volunteering or philanthropy.

What the world needs now …..

Songs of disillusionment

In 2005, prolific songwriter, Burt Bacharach released ‘At this time’, his first album of songs with his own lyrics. The album has a political and social motivation, as he laments the safer and more loving world he once knew and believed in, and blames lying politicians and greed for breakdowns in society. “I keep hoping for a better day/ It’s a long time coming but I wait anyway/ Life’s a miracle or a foolish tale/ I don’t know – go ask Shakespeare.”

Dying for want of a story

Sociologist John Carroll (author of “The Western Dreaming: the western world is dying for want of a story”) believes that humanism has so far failed to provide a livable philosophy. “Nihilism …. is the inevitable end point of the humanist cultural experiment. Needless to say, humans cannot live with the ultimate conclusion that this is all there is.” He says we desperately need “persuasive answers to the central metaphysical questions. Without such answers we humans cannot live.” He suggests that an increase in various forms of fundamentalism is likely to result from this lack.

The world is an iron cage

Sociologist Max Weber agrees (“Reality has become dreary, flat and utilitarian, leaving a great void in the souls of men which they seek to fill by furious activity and through various devices and substitutes.”), arguing that with the progress of science and technology, we have lost our sense of the sacred, and the world has become an ‘iron cage’.

Assessment

To be fair, the “blame” for these negative impacts must be shared between religion and secularism, but it is undeniable that many of these adverse trends in society correlate with secularisation.

When one includes the impacts of communism during the twentieth century, it is hard not to conclude that non-theistic belief systems have increased human misery, whatever their original motivations may have been. It is more difficult to judge non-theistic belief in western democracies because it is mixed with theism and an ethical system which has been inherited from christianity.

Which of the several non-theistic belief systems works best?

- Nihilism is not attractive, except in a dark and heroic kind of way, because it is without hope and ethics, two things which most of us find difficulty living without. Suicide appears to be (and has often been) a logical end point of nihilism, but defiance and choosing to live as if life has meaning is another option.

- Hedonism is much more attractive to most of us – if only we are among the few who have the means to pursue pleasure to sufficient extent. But studies show it may bring less happiness than we might expect. Nevertheless it remains an option, and often a choice, in western societies, despite appearing to many people to be selfish and not very admirable.

- Humanism is the most attractive option for anyone wishing to live a life with meaning and purpose, but it can be hard to maintain optimism. It is probably true that most western secular people live a life where a frustrated hedonism is mixed with humanism (in their best moments) and occasional bouts of nihilism (in their worst).

The end of the matter?

We have only been able to scratch the surface of a few issues relevant to the question of how each philosophy of life works out in practice, and thus whether religion poisons everything or enhances everything. And we have found that the impacts of the various belief systems on individuals and society are many and complex. Each person brings their own perspectives, and will draw their own conclusions, based in part on personal experience. Here are mine.

Neither religion or unbelief are the main causes of misery

It is difficult to disentangle the various contributions of belief (theism or atheism), nationalism, commercial greed, social customs of the day, etc, to come to a definitive answer. Any definite conclusion must be partly subjective. However historical and current research lead me to the conclusion that neither theism nor atheism has been the principle cause of many of the evils that may be attributed to them – it seems that nationalism, political power and personal gain were probably bigger factors in most cases.

Christianity and theism generally

Christian theism seems to have brought the greater improvement to human happiness throughout history and into the present day. However in the past it has also been associated with many oppressive and destructive actions, mostly performed by states but sometimes by the church. Some forms of theism (notably Islam) can sometimes still be associated with oppression. Christian theism seems to be most beneficial to life when believed by individuals who act on their beliefs and try to follow in the steps of the founder of their religion, and most dangerous when systematised into a dogmatic religion and allied with the state to give it great power.

Unbelief

The non-theistic belief systems are attractive to many, principally because they seem to offer a more contemporary, independent and scientific approach to life, plus freedom from the burden of religion. However none of the three approaches (nihilism, hedonism and humanism) seems to be logically and easily livable on its own, and adherents may tend to move somewhat inconsistently between all three at times. On the other hand, non-theistic and anti-theistic worldviews have, in the twentieth century, been associated with oppressive and destructive ideologies (communism and some forms of fascism) on an unprecedented scale. Again, non-belief seems to work best when followed by altruistic individuals, and least well when systematised into totalitarian political systems.

A personal view

Perhaps it is my bias, but it seems to me that christianity has, overall, had the greatest positive impact. The teachings of Jesus have motivated many people to altruism, but the church has been a mixed blessing, with much we can be thankful for, but much that requires repentance. Non-belief seems to have produced less benefits to the human race and, in the twentieth century, a terrible cost when expressed in the form of communism. I think Christopher Hitchens was partially right, but ultimately mistaken.

What do you think?

Make the world a better place

If you feel inspired to make the world a better place, and work against the bad and ugly described here, here are some places you may like to start. If you have other suggestions, please let us know.

References

The information for this topic was taken, in part, from the following sources.

Health and wellbeing

In faith and wellbeing I list a number of studies showing that there is a strong positive link between faith and wellbeing (both mental and physical health).

Who contributes to society?

Studies by the Barna Group show that in the US, theists (21-33%) are more likely to volunteer to work for non-profit community organisations than atheists or agnostics (14%). The original article is no longer available, but it is discussed in this report. Other studies gave mixed results: this study showed that believers, especially some groups of believers, were more likely to do volunteer work in the community, whereas another study showed little difference between believers and the community as a whole.

In his 2006 study Who Really Cares: The Surprising Truth About Compassionate Conservatism, Arthur C. Brooks found that religious belief was one of the two biggest predictors of altruistic giving. Read more about his findings as reported by ABC News.

Volunteering by the Christian Research Association, based on the Australian Bureau of Statistics, NCLS research and Edith Cowan University. In Australia, attendance at religious services was one of the two most important factors in a person doing volunteer work in the community.

Religion and Spirituality of people born between 1976 and 2001 in Australia (from The Australian Clearinghouse for Youth Studies, a government organisation). “Participants actively involved in community service were likely to have spiritual and religious beliefs and actively practise them.”

The effects of religion on people’s ethical behaviour

Studies reported in the Science on Religion blog:

- Not conservatives, but religious people, more charitable

- Does religion make us moral?

- Does religion turn people into haters?

Tom Holland: Dominion: The Making of the Western Mind. Information taken from History for Atheists blog. See also a review of Holland’s book in Religion Unplugged.

Statistics on genocide, war, terrorism and mass killings

Which has killed more people? – an anti-christian website that attempts to score how much religion or non-belief contributed to mass killings. It concludes that christianity is culpable in 4 major events in which about 30 million people died (the worst being the conquest of the Americas, in which it estimates about 20 million died) and that non-christian belief systems (mainly Nazism and Communism) are culpable in 4 events in which 75-100 million people died. A further 9 events in which about 70-80 million people died have unclear culpability.

I think this site overstates the impacts of both belief and non-belief, because:

- It estimates the culpability of religious belief, but does not consider the joint culpability of other contributory causes such as nationalism, political leadership, greed, etc. It is probably impossible to ever separate the influences of belief from the other influences.

- Rodney Stark (see below) claims that governments and not the church were clearly responsible for the millions who died in the Europeam conquest of the Americas, and atheism was probably not the main factor in the millions of deaths under Chinese and Russian communism.

- It is unfortunately easier to kill large numbers of people in the twentieth century because of “improved” technology and the greater population, so comparisons and totals are almost meaningless.

Nevertheless, the figures indicate a sorry record for institutional christianity, and a worse record for institutional non-belief.

Several independent expert studies on the causes of war and terrorism are at Does religion cause terrorism? and Does religion cause war?. These studies all indicate that religion is a major causes of only a minority of conflicts and terrorist acts.

Genocides in history (Wikipedia). But see also revised information by Rodney Stark (below)

In his book Atheism Explained, atheist David Ramsay Steele sums it up: “The history of the past one hundred years shows us that atheistic ideologies can sanctify more and bigger atrocities than Christianity or Islam ever did. The casualties inflicted by Communism and National Socialism vastly exceed – many hundredfold – the casualties inflicted by theocracies. In some cases (Mexico in the 1930s, Soviet Russia, and the People’s Republic of China) there has been appalling persecution of theistic belief by politically empowered atheists, exceeding any historical atrocities against unbelievers and heretics.”

Religious persecution

Broken people, broken promises, Institute for Public Affairs & Dalit Freedom Network. Hindu persecution of Dalits (“untouchables”).

Inquisition. Crusades. Wikipedia. But see also revised information by Rodney Stark (below).

China’s christians suffer for their faith. BBC News.

Political prisoners. Amnesty International report on Saudi Arabia.

The behaviour of the church in the Middle Ages, both good and bad, is well described in James Hannam’s God’s Philosophers: How the Medieval World Laid the Foundations of Modern Science. Included in the book are an outline of the work of many medieval natural philosophers (precursors of modern scientists) and a discussion of the church’s dealings with Galileo.

As an example of how myths about the church’s opposition to science develop, read this review by an atheist amateur historian of the film Agora, which is based on much that is unhistorical.

Impacts of atheism, humanism and theism on society

A summary of the contents of Christopher Hitchens’ book God is not great: How Religion Poisons Everything

Writings of John Carroll.

Societies worse off when they have God on their side. Times Online.

Writings of Rodney Stark, and Rational Choice: why monotheism makes sense (a summary of the historical research of this academic sociologist).

People’s stories

Changing Lives online – christian stories.

Exchristian.org – stories of people who have moved away from christian belief.

Converts in the houses of the Lord. Sydney Morning Herald, November 2003.

The Wild Gospel. Alison Morgan. Monarch Books.

Feedback on this page

Comment on this topic or leave a note on the Guest book to let me know you’ve visited.