How can believers and unbelievers disagree so strongly?

We all experience the same world, we have the same information from science and history. If it was anything else but religious belief, you might expect opinions to be a little less polarised. But highly educated people like Richard Dawkins and William Lane Craig disagree profoundly even though they are both responding to the same information. Atheists and christians on the internet can be just as polarised.

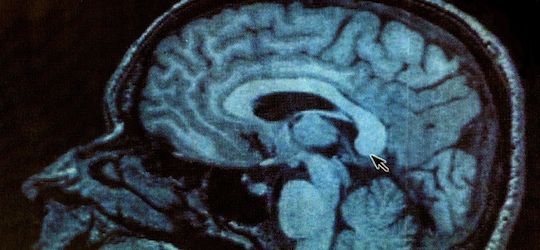

No doubt personal experience plays an important part, but I wonder whether new understandings of the human brain provide another part of the explanation.

Neuroplasticity

The human body is remarkably resilient. If we accidently cut ourselves, the cut heals quickly. But it was long believed that our brains were the exception – damage was thought to be irreparable. But neuroscience has now found this is far from the truth.

As we learn and grow in the early stages of life, the brain is very ‘plastic’ – it is constantly setting up new pathways and connections to best respond to the inputs it is receiving. But even as adults and into old age, it remains plastic (to a degree).

If part of our brain is damaged, another part can often take up the load. If a part of our body is damaged and the part of the brain that controls it is no longer needed, it can be redirected to other tasks. If we start to learn new skills or focus on some aspect of life or knowledge, our brain can adjust, forming new linkages, pathways and maps to improve our abilities or recover lost abilities.

These are not just improvements in the way we use our brain, but actual physical changes – increases in the number of neurons and changes to the ways they are connected.

We can change our brain structure

Sometimes these changes happen quite naturally, but sometimes they require disciplined training. With training, we can improve our abilities, brain functioning, memory and even intelligence – recover lost abilities, slow the onset of aging, repair damaged areas, recover from strokes, and reduce the effects of depression or cerebral palsy.

And we can also improve normal brain functioning, if we know how.

You can sculpt your brain just as you’d sculpt your muscles if you went to the gym

Neuroscientist Richard Davidson

It happens all the time

The interesting and perhaps scary thing is that we are changing our brain structure and functioning all the time, for good or ill, depending on what we give our attention to.

Our brains are continuously being sculpted, whether you like it or not, wittingly or unwittingly.

Richard Davidson

neuroplasticity …. renders our brains not only more resourceful but also more vulnerable to outside influences …. some of our most stubborn habits and disorders are products of our plasticity

Psychiatrist Norman Doidge

This even affects our thinking about God

Studies show that religious practices such as prayer and meditation improve both mental and physical health because they change the way our brains function. And what we focus on affects our thinking even about God:

The more you focus on something — whether that’s math or auto racing or football or God — the more that becomes your reality, the more it becomes written into the neural connections of your brain.

Neuroscientist Andrew Newberg

Opposing beliefs about God?

I can’t help feeling this helps explain the strengths of opposing views about God.

Not only …..

Sceptics commonly criticise christians for holding onto belief in God with faith that is stronger than the evidence. And these neuroscience conclusions suggest this is probably the case.

Christians choose to believe for a wide range of reasons, and sceptics may legitimately critique these reasons (though they often seem to misunderstand them). The christians’ choices will naturally lead to them focusing on God in new and positive ways. God will generally become more central in their thoughts, they will gradually (sometimes rapidly) change aspects of their life and thinking to conform to their new belief, and they will gain the mental and physical health advantages of belief and prayer.

All this occurs regardless of whether christian belief is true or not. If their belief is true, as christians believe, neuroplasticity will be working in their favour. And even if christian belief is mistaken, at least the health benefits will be real.

And so christian belief and commitment is strengthened and they will (generally) find it increasingly difficult to see the logic of scepticism.

…. but also

But of course similar things can be said about sceptics.

Sceptics choose not to believe for a wide range of reasons, and christians may legitimately critique these reasons (though they may often misunderstand them). The sceptics’ choices will often lead to them focusing on reasons for disbelief, and their focus on God will be negative. They will gradually (sometimes rapidly) change aspects of their life and thinking to conform to their new disbelief, but they will have to deal with the mental and physical health disadvantages of disbelief.

Additional note: Several commenters have misunderstood this statement, so I want to clarify it. The positive effects of belief on wellbeing, and hence the relatively less positive outcomes for non-believers, is a trend, not an absolute. It isn’t the same for all believers and all non-believers, but rather there is a correlation and apparently a measure of causation.

All this occurs regardless of whether their disbelief is true or not. If their disbelief is true, as sceptics believe, neuroplasticity will be working to strengthen that disbelief. And even if their disbelief is true, the less positive health effects will be real.

And so their commitment to disbelief is strengthened and they will (generally) find it increasingly difficult to see any logic in belief. Though they may aspire to be rational and evidence-based, they will find this increasingly difficult, because neuroplasticity is changing their brains too.

A slightly depressing conclusion?

Do you find this pair of conclusions slightly depressing?

I do. But it does help explain why relations between believers and unbelievers are often so polarised, with each side confident of their viewpoint and so uncomprehending of the other. It explains why some christians accuse sceptics of dishonesty and worse, and why some sceptics resort to epithets like ‘delusional’ and having ‘blind faith’ to describe believers. And the more each side repeats these claims, the stronger will become the neural pathways that make this thinking seem right and inevitable.

Is there a better way?

There are clearly ways to improve our brain functioning. And I believe there are better ways for both believers and unbelievers to deal with the closing and hardening of our minds.

That will be next post.

Further reading

- Are our brains like computers?

- The brain that changes itself. Norman Doidge

- Neuroscientist Andy Newberg on belief and the brain

Photo Credit: Mikey G Ottawa via Compfight cc

I enjoyed this post, and I appreciate the research you did for it. I disagree a bit with the way you made skepticism sound in this part:

I wouldn’t consider it a given that non-belief leads to poor health or “negative effects.” I agree that focusing on negative things can lead to poorer health — that’s been known for years, and it makes sense. But non-belief is not necessarily a negative thing. It’s been a positive thing in my own life. And in part, I’m sure that has to do with the fact that the brand of Christianity I left believed in a literal Hell and that most people would be going there. Pretty depressing.

But also, I just find the universe to be filled with much more possibility now that I’m no longer religious. I have a greater sense of awe and wonder — I don’t tend to take so many things for granted any more. It’s even been one of the factors that’s helped me get into better shape physically.

And on the other side of the coin, religious belief can sometimes lead to physical and emotional problems. We can’t ignore those groups that shun modern medicine because of their beliefs. Or those who don’t take charge of their own lives, thinking God is controlling everything. And studies have also shown that for people who fall into poor health, religious beliefs can sometimes have a negative effect, because they think God is punishing them for something.

I do think neuroplasticity is interesting in understanding why people view things in different ways. And I’m not surprised that some correlations have been found between religious belief and health. I just wanted to put out the reminder that these would not hold true in all cases, and they don’t really play a factor in what is actually true. I know you would agree with that — I just wanted to state it. 🙂

Hi Nate, thanks for your comments.

Yes I do agree with your last paragraph. I tried to fairly report the results, and you’ll find a few words like “generally”, “commonly” and “often” in there, indicating that these results are statistical, not determinative. I don’t know how strong the correlations are, but they are significant though nowhere near absolute. I’m sorry if I gave any other impression.

I did also say that the results were irrespective of the truth of belief or disbelief, and I deliberately framed my words to be even-handed.

But the health results are the one place where I couldn’t be even-handed. When I commented about neuroplasticity on your blog, I hadn’t yet read the findings of Andy Newberg on religion and the brain, but once I did, improved health outcomes was so much part of his conclusions that I had to include it (see the link at the bottom of the post).

Of course many christians are unhappy, unhealthy and maladjusted and many sceptics are the opposite, but the results are very clear – there is a distinct correlation between various religious beliefs and practices (and not just christian ones) and a whole bunch of improved mental and physical health outcomes. And yes, there are anomalies, as your reference indicates.

Interestingly, some practices like meditation and prayer are effective even if followed by non-believers (not sure how a non-believer could pray, but some AA people achieve this). So if atheists meditate and forgive, for example, they will get the benefits (statistically), it’s just that presumably most don’t, in any systematic may at least.

I have a whole bunch of references, for and against, from the Science on religion website, I have posted on a few, and will be posting on a few more as a follow-up to this post. Watch this space! 🙂

I suppose “AA” means “Anonymous Alcoholics” here and not “American Atheists”. 😉

Yes. (Well Alcoholics Anonymous, anyway.) Your Dutch sense of humour triumphs again! 🙂

unkleE, could you please provide some ideas for a skeptic that wishes to find whether a god exists or not? What would be some things to focus my thinking on that would prevent narrowing my focus in one direction? I am reading your other articles, but is there anything in particular you would recommend? Thanks.

Hi Dave, thanks for your question. I’ll be covering some of this is my follow-up post, and I still have a little thinking to do, but here’s my thoughts so far.

We all have wishes and apprehensions, including about God – some people want God to be true, some don’t. If we train our brains according to what we focus on, to some degree at least, then it is probably more likely we’ll end up believing what we want to be true – not certain, but more likely.

So I think the first thing is an attitudinal one – to recognise what our own wishes are and decide if we really want to go with them . So a sceptic has to decide if they really want to know God if he is there.

Secondly, I think those of us (sceptic or not) who want to know truth have to expose ourselves to a range of opinion, and not just read those with views similar to our own views. Most people, in my experience, don’t do this.

Likewise, when we think of the various arguments and evidences for and against God, we need to consider all of them. For example, if we focus only on the evil in the world, we’ll be filling our brain, and perhaps changing our brain, with thoughts that make God seem unlikely. Likewise, if we focus (say) on the fine-tuning of the universe, or apparently miraculous healings, we’ll be reinforcing belief.

This is especially important while we are making up our minds, but I think it is still important after we have made our choice. So, for example, I have made my choice to be a christian, but I still try to read both sides of questions, or at least neutral authors (e.g. the 3 main authors on which I have based my comments on neuroplasticity are all non-believers as far as I can tell). That way I can stay somewhat sympathetic to viewpoints I don’t believe are correct, and can continue to test and refine my belief.

None of us can be perfectly neutral, but we can avoid focusing on the extremes.

I’d be very interested to hear more of what you are thinking – about this topic, or about what you have found on this web site. Thanks.

Thanks for your reply. I do think that I would like to know God if he is there and I would very much like to know if he is there or not. I’ve given myself a challenge however, because I’ve decided that I can’t believe he’s there just because I want him to be.

I agree with your second point as well and have tried to read as many different views on this as I can find. I consider myself agnostic and have a great desire to know if God exists. I have looked at a lot of different topics from physics to biology to philosophy and so on and have watched many of the debates on this question. I appreciate the balanced view you provide and will be spending some more time reading your web articles.

One problem that haunts me is this: If God does exist, he must be very complex. More complex than this universe and it’s inhabitants. I’m not sure how to account for this kind of complexity and I’m left asking myself what seems more probable: Something extremely complex existing for all time, something (matter/energy) coming from nothing or something simple (say, sub-atomic particles) existing for all time.

Hi Dave, thanks for filling me in on where you’re at. I certainly agree that you can’t choose to believe something this important just because you’d like it to be so.

I’m glad you’ve found this site useful in some way, and I hope it can help you think through some of the evidence and arguments. I think philosophy and evidence can only take us so far. They may lead us to conclude that it is more probable that God exists than that he doesn’t, but I think strong belief in God also depends on God doing something to help us know him. This may be through belief in the historical Jesus, or through some experience of God, or just through God convincing us in our minds, but I think something like this must be part of it. That’s why I have stuff on philosophy and science but also on history and people’s experiences.

I’ve never found the complexity issue much of a problem. It isn’t clear exactly what we mean by ‘complexity’ in this context. Complexity can mean having lots of parts (like in a complex jigsaw puzzle), but one could hardly say God has lots of parts. Perhaps we mean hard to understand, but I don’t see how that would make God less likely. How would you define complex in this context?

Thanks again for your comment. I would be interested to discuss any matters you find of interest here. Best wishes.

I would define complexity as having many parts and in this case capable of profound abilities like creating the universe. I wonder why you think it could not be said that God has lots of parts. I see only two options: either God is made of something or he is made of nothing. In this case the something could be supernatural and well beyond our understanding, but we can at least say it is more than nothing. Is this something simple or complex? I think most believers would say it is complex and perhaps to the point of infinity. If God has infinite knowledge, doesn’t this knowledge have to be stored within himself leading to the conclusion that he has some parts for this purpose?

Perhaps I will be accused of trying to define God using my limited cognition, but I think there are some things we can say that transcend all limits. We can say that something either exists or it doesn’t. There are certain black and white definitions that all things must adhere to whether natural or supernatural. Things can either be true or false, something or nothing, conscious or unconscious, simple or complex.

I don’t think God is complex “physically” like a puzzle, but is complex in a general sense. I’m not trying to define the parts, just stating that they exist if God exists. Does this make sense? Thank you for any feedback.

Hi Dave, I am finding this very interesting, thanks, as I haven’t done much reading or thinking on it before. So this is good, and I like the idea of us approaching this as two people working together to nut something out.

When faced with the questions you ask and the points you make, my first thought is to try to write this down as an argument in the form of a series of propositions. Here is my first attempt:

1. We define complexity as either (a) having many parts, or (b) being hard to understand.

2. (a) A cause is more complex than its effect or (b) a designer/creator is more complex than what he/she creates.

3. Therefore God is more complex than the universe.

4. A complex thing is less likely to occur naturally than a simple thing.

5. Therefore God is less likely to occur than the universe.

6. Therefore God doesn’t have any explanatory power.

7. Therefore God probably doesn’t exist.

I’d welcome any suggestions to improve that. But as it stands, I think every one of those propositions is doubtful at best, and quite unlikely at worst. I won’t go into too much detail now, but here’s a few thoughts.

1. I don’t think either definition is very relevant for God (I don’t think your explanation of God having parts holds – a brain has parts, but does a mind?).

2. I think this is extremely doubtful.

(i) Biological evolution shows that it isn’t always true.

(ii) Mind and consciousness are often considered emergent properties of the brain, to explain how non-physical can arise from physical. This seems to offer a possibility not considered by this premise.

(iii) People have been able to invent computers that can play chess better the the world champion, because they are capable of analysing more complex positions and lines of play than can the world champion, a clear contradiction to the premise.

3. So I don’t think this has been demonstrated, because we don’t have a good definition of complexity that applies to God, and #2 isn’t universally true. Theologians have since the early centuries of christianity argued that God is simple in essence. One argument is that zero (nothing is possible) and infinity (everything is possible) are both simple concepts compared to intermediate states where many things have to be specified in terms of possibilities. Thus the existence of nothing, or of an infinitely knowledgable God are argued to be the least complex possibilities.

4. This is generally true in the natural world, because complexity requires more steps to achieve. But it certainly isn’t always true. e.g. if you used theoretical physics to define the possible ranges of physical parameters and laws that controlled the universe since the big bang, the universe we live in is one of the most complex possible.

But if we modify the premise to something like: “Other things being equal, a cause is more complex …”, how do we define those other things? And why should what we find more often in the natural world be true of God?

5 & 6. So if we consider other factors like the implausibility of something arising from nothing and an infinite sequence of events, we can argue “that other things” are not equal, a temporal universe created by an eternal God is a much more satisfactory explanation than that a temporal universe that is ‘running down’ appeared for no reason or has existed forever. Yes it posits one more entity, but that entity is in some respects simpler than the universe (it has many less parts, for the universe has 10^80 baryons) and it explains far more than the alternative explanation.

So, like I said, I haven’t even thought the complexity argument was much more than a theoretical one. We cannot fully understand God, but we can understand why that is.

I’ll be interested to explore this further with you.

Finally, here is a useful reference, which is written by a christian but doesn’t always agree with me.

With all due respects, this seems a very sweeping statement.

I hardly think one could apply the same maxim to those ”trapped” in many forms of fundamentalist religion.

The mental well-being of young children who are subject to the teachings of ACE, (Accelerated Christian Education -http://www.aceministries.com/global/?content=asiaPacific) which can be considered bordering on abuse, can hardly be regarded as possitive.

http://leavingfundamentalism.wordpress.com/2013/09/07/creationism-alive-in-scottish-state-primary-school/

And this goes for all forms of Christian Fundamentalism.

I would venture a similar negative mental outcome would be seen from some of the abusive tenets of Islam.

Surely, those who escape from such mind-numbing religious practices will experience a noticeable improvement in their mental well being?

And this will inevitably lead to an improvement of their physical well being.

Would you consider religious fundamentalist beliefs as having long term positive mental health benefits?

And if this is found to be true would you consider it is morally and ethically defensible to encourage such beliefs?

Hi Anonymous, thank you for “due respect”, and you are right, it was a “sweeping statement”.

I was writing about neuroplasticity, and this was just a small part of the findings of one scientific study, so I only mentioned it briefly. But the finding stands on good evidence.

There is a most interesting blog, Science on Religion which reports on recent studies on religious belief. There are all sorts of connections and findings, some positive, some negative, but the connection between religious belief and practice and wellbeing is very strong across a lot of studies and different aspects of wellbeing. I have blogged several times on some of the findings, and intend soon to do a summary blog of many of the more obscure and sometimes bizarre ones. I have written a brief summary, but need to update this page.

But of course the findings are statistical, what happens more often than not, and are nowhere near absolute, so there will be many christians to whom the findings don’t apply, but many more to whom they do. That’s why I used words like “generally” and “often” in my summary.

I have some familiarity with ACE, and fundamentalism in general, but I wasn’t specifically writing about these aspects of christianity. Depending how you define fundamentalism, it is only a minor viewpoint within christian faith. The studies I referred to would have included fundamentalists without distinguishing them from others (generally) and perhaps they would be the ones who have lower wellbeing. But I would expect they would be the same as everyone else – some doing well, some not so well.

So I expect many who leave such forms of christianity would improve their wellbeing, whereas those who stay might already be happy and healthy.

Thanks for your comment. Do you have a background like you describe?

Hi Far King,

I haven’t seen studies on “religious fundamentalism” as distinct from other forms of religious behaviour and belief, and I imagine it might not be easy to find a clear definition for use in such a study. I vaguely recall that studies find that believers in a strict or angry God are more likely to behave morally, but may have lower mental wellbeing, so that may illustrate the question.

How the positives and negatives balance out would vary from person to person I imagine. But since I don’t hold a belief that I guess most people would call “fundamentalist”, I don’t feel I really have to consider the question you ask personally.

Thanks for your interest.

If such people do in fact exhibit signs of poor mental well being, and this would seem quite likely if their beliefs were based on ”a strict or angry God” would you consider their apparent moral behaviour is largely due to the fear factor?

Are you/do the studies you refer to make any mention or suggestion that such moral behaviour would deteriorate or improve should these people leave such an environment, especially if they rejected this form of fundamentalism altogether and opted for a non-religious lifestyle?

“would you consider their apparent moral behaviour is largely due to the fear factor?”

It is difficult to say, but I would guess that may be correct for many. I think many, both believers and non-believers, have this view of christian ethics, but I regard it as mistaken. I think christian ethics are properly based on a response to God’s love, not to fear of his anger.

“Are you/do the studies you refer to make any mention or suggestion that such moral behaviour would deteriorate or improve should these people leave such an environment, especially if they rejected this form of fundamentalism altogether and opted for a non-religious lifestyle?”

I think most studies, being based on something akin to evolutionary psychology, would argue that our character and ethics are built in by evolution, and therefore most people would be the same whether they are religious or not – fearful people are fearful whether they believe or not. I would have a slightly different view, as I believe we see people changing their behaviour when they change beliefs. So I think some people leave religious belief for good reasons, and some for bad, with both good and bad consequences. Some of those who leave for good reasons and good consequences return with a better attitude and a better result – better in terms of their state of mind.

What do you think?

Fundamental Christianity, which is what I was referring to, does use the ‘angry god’ tactic, especially on young children during the initial stages of indoctrination. I have read several sites where former Fundamentalist Christians have in fact stated this. Maybe they are isolated cases, but it seems unlikely based on their personal testimony. The Old Testament is a litany of examples, is it not?

I am not questioning whether this a wrong belief – of course it is – but the fact that it is a belief that is prevalent among many Christian denominations.

Surely you cannot accept this as a blanket diagnosis?

If a child is brought up in a loving family environment irrespective whether the family is religious or nonreligious the child will respond in a positive, healthy way whereas in a fearful environment the health,mental as well as physical, of any child will suffer tremendously.

And in a religious environment where God is seen as having more power and more authority than the child’s parents, for example, being forced to believe in a tyrannical God must be even worse.

Are you suggesting this is not so?

From what I have read, few people who escape from such an environment ever return. In fact many seem more opposed to it after deconversion. And in case you may ask…no, I have never been in such an environment

If our character and ethics are built-in as you suggest is there really validity in suggesting religion engenders any more positive traits than a non-religious environment?

Hi, I think you are being a little too black and white here. I think reality is much more nuanced.

1. I don’t think anywhere near all “fundamentalist” christians use fear as a tactic in a nasty way. Of course a low level of “fear” is used in all upbringing – e.g. be careful when crossing the road. Many (most?) fundamentalist christians are very loving.

2. So I think your dichotomy of “loving family environment” vs “fearful environment” is too stark. Families can blend different attitudes.

3. Likewise your use of the word “tyrannical” is too emotive. A person can think God is angry with sin without thinking him to be tyrannical, and most christians think God is loving even though he may be angry with some practices. And we can see parents for whom this is true too.

There are undoubtedly some christians, and some non-believers for that matter, who harm their children in their upbringing, but I think you may be drawing fixed and sometimes unjustified connections here.

Where do you want to go with your comments and questions?

I don’t want to go anywhere; sorry if you feel this way. I was responding largely to the comment picked up by Nate.

”And even if their disbelief is true, the negative health effects will be real”

Things just developed from there.

I just feel this comment seems unsubstantiated and it tacitly implied that if one does not believe in God then one’s mental well being will be worse than a believer’s. It seemed a misleading statement so I sought clarification.

I agree and I find it very interesting as well. Thanks for linking to that paper, it was very relevant.

By saying God is made of parts I was not restricting those parts to being physical (like a brain). I was using the word parts to refer to both physical and non-physical things. In this case, even our mind is made of parts: thoughts, feelings, memories, ideas, etc. and some thoughts are more complex than others.

On a side note, I am not sure whether our minds would exist without our brains, but either way I would describe them both as being complex.

What if we defined complexity as being comprised of many parts (physical or non-physical) and/or having many abilities. We could then measure the complexity of an entity by looking at the number of its parts and also by what it is capable of doing.

So if we had a human and a dog side by side we would say that a human was more complex because it could build a house and solve math equations. The human also has more neurons than a dog according to this list.

Whereas if we compared a human to God we would say that God is more complex because he is capable of designing and creating the universe.

That may not be the best way of measuring complexity, but it seems intuitive to me.

Another thing I’m still puzzling over is whether infinite knowledge is even possible. Perhaps “knowledge of everything” is what we mean rather than infinite knowledge. Because once someone reaches the point of knowing everything there is to know it seems impossible to continue adding knowledge to that and continuing to infinity.

Sorry if I did not respond to all of your points, but it’s time for bed here. Best Regards.

I think you have misunderstood me, and since others have misunderstood as well, I mustn’t have been clear – I’m sorry.

The studies clearly show that religious belief and certain religious practices have a number of beneficial effects on physical and mental health – on average. So, on average, non-beleivers don’t do so well in these areas. But I say “on average” because it is a statistical thing, it’s nowhere near absolute.

So in my blog post I used words like “generally”, “often” and “commonly” to indicate a trend but not an absolute. I will amend the text to clarify this.

But with that clarification, the results are very much substantiated, if you read the reports.

Do these studies refer to specifically the Abrahamic God, and Jesus, or does it include god belief across all religions in general?

Hi Dave,

I feel this is pushing things a bit. Thoughts are parts? I can’t see that. They are outcomes or something. Take a computer analogy, is the result of a calculation a “part”? Or are our words “part” of us? I think we need more rigour than that in our definitions.

Again, I think we need more rigour. And the 7-step argument I suggested before is surely the way to introduce rigour. I suggest the definition of complex has to be one that fits that argument.

As I have formulated it, the key step for this is: “4. A complex thing is less likely to occur naturally than a simple thing.” So is a thing with more parts or capable of doing more things less likely to occur naturally? In the natural world, that seems to be sometimes true – e.g. bacteria are more prevalent than dinosaurs or elephants. But with elements in the periodic table, it isn’t so clear. Sure the two simplest (H and He) are the two most prevalent in the universe, but as you move up the table in order of atomic number (and hence complexity) there is less of a correlation – for example the next three – Lithium (3), Beryllium (4) and Boron (5) are all less prevalent than the next 20, more complex elements.

But when we are discussing God, it is even more problematic. God is hypothesised to be mind without body, but in the natural world, mind is hypothesised to be an emergent property of the brain, and not to exist on its own at all. I can’t see how it can be complex if it is just an emergent property. So if God is mind, he is surely more powerful than our minds, but proposition 4 doesn’t apply to him.

So if the argument is to work, I think you need to formulate it in a way that every step, including the definition of complexity, applies to a God who is mind but not physical brain, and I don’t think you have done that yet.

Yes I agree with you here, and so do the philosophers. They usually define omniscience as “knowing everything that can be known”. The use of “infinite” is just an inaccurate shorthand.

Thanks again, I look forwards to your thoughts.

There are different studies, but in general I’d say that (i) the conclusions refer to God-belief and religious practices in general, not specifically, (ii) most studies are in US and UK, so christian belief is most often the one studied, but Judaism, Islam and other faiths are sometimes (often?) included, and (iii) it appears that some practices like meditation ‘work’ even with unbelievers.

I could not find anything in Newberg’s paper/interview on the link where he states that there are direct negative mental effects from not believing in God or following religion, even though he suggests some form of God consciousness is in our brains. This could, of course, be simply down to cultural attitudes.

Maybe I missed the bit about the negative effects?

In all honesty, I felt his allusions were not that specific at all and seemed to tie in more with spirituality/meditation rather than anything religion-specific. He even stated that he wasn’t religious and didn’t mention whether he believed in God.

I am quite familiar with the benefits of meditation and visualisation and use them in a general way and have employed such techniques as pre-race specific preparation when I used to regularly run marathons and can attest to the relaxing benefits and overall feelings of calmness.

That I am not in the least religious has never impacted negatively on my wellbeing at all, (not that I am aware of, but how would I test something like this?) though I do know one or two people that have suffered emotional trauma and have found solace in religion, so maybe religion does fulfill an emotional need for some people.

But from Andy Newberg’s brief paper/link it seems to be stretching it to suggest that God belief is a panacea to mental well being.

Hi unkleE,

I am trying to think of a more specific way to define complexity. To say that it is just based on the number of parts could be problematic. In that case a mountain would be more complex than a man. I thought “abilities” might be a good measure, can you think of another?

If a human mind were somehow translated into a computer program, wouldn’t we consider it a fairly complex program?

So if God is a mind I think it would also be complex. I will try and think of a way of phrasing this with more rigorous definitions.

Dave

I’m appreciating this discussion as I haven’t thought all that much about this before.

I think we are now agreed that the idea of parts isn’t going to work, as your mountain example shows. I think this is (i) because the idea is too physically-based to relate well to God and (ii) it doesn’t work with the 7-step argument. Let’s try your idea of abilities.

Clearly propositions #2 & #3 work under this definition – God has more abilities than the universe so he is more complex than the universe.

Proposition #4 now becomes “4. A thing with greater abilities is less likely to occur naturally than a thing with less abilities.” Is this true?

In humans (the highest form of life we know, and hence closest in many ways to God), it doesn’t appear to be – a genius is born in exactly the same way as a low IQ person, and the frequency distribution of abilities would seem to be a normal bell curve. And if we consider theoretical physics, our universe has more “abilities” (e.g.. it can synthesise carbon in supernovae and thus provide the building blocks for life) than almost all the zillions of universes that are theoretically possible, yet it is the one that actually exists – so again, there seems to be no barrier to a complex universe existing.

And if we consider that God is usually defined as the creator of this “finely-tuned” universe, it seems more likely that he would exist (and the universe would exist) if he had many abilities than if he didn’t.

So I still don’t see how the argument can be made to work. And I think it is clear why. The idea of complexity being less likely is almost certainly an idea we get from biological evolution, where it appears to be true – certainly there are fewer of the “higher” species and they took longer to appear. But no-one is surely suggesting the if God exists, he came about via a process of biological evolution!?

I really think the argument is a lost cause. It relies on concepts from the physical world and from evolution that cannot be shown to apply to God, and would appear to almost certainly not apply to God. I don’t think coming up with another alternative definition of complexity is going to save it.

No, I think that is correct, but it isn’t what I was saying either.

His, and many other studies, show that people who believe in God and/or participate in certain religious practices, are happier and healthier, on average, than the norm.

This means, by simple mathematics, that people who don’t believe or participate in those practices must be less happy and healthy, on average, than the norm. It isn’t that their lack of those things makes them less healthy, only that it means they are less healthy and happy than average. That’s just the way averages work.

Sadly this is a bit of a misleading statement and somewhat an abuse of the information, unintentionally I am sure, but your deduction is not quite an accurate rendition regarding non belief.

He did not specifically say that those who believed in god are healthier or happier at all.

It’s only fair to recognise what Newberg did and didnot say and not interpret to arrive at an unfair conclusion based on supposition rather than actual fact.

Newberg said:

He also suggested there could be serious negative effects

Newberg mentioned certain religious practices and specifically prayer/meditation. The latter I also do and as I have already mentioned and gain benefit from and yet I am not in the least religious, and would, in fact, consider religion anathema and highly detrimental to my health, especially based on general evidence of behavior of many religious people, especially those who are considered fundamentalists.

And again, I would direct your attention to the numerous bloggers who have escaped from such organisations and deconverted who will state emphatically the horrendous levels of mental abuse they suffered during their time with such religious organisations, Christian or otherwise.

What Newberg is actually saying is that in certain cases studies have noted definite benefits for some people who in God and participate in certain religious practices.

This is agreed and is perfectly acceptable.

To use the Newberg’s survey to try to convey blanket health benefits of god belief is probably a little dogmatic.

Hi.

I have said:

* religious beliefs and practices generally (but not always) help people achieve better mental and physical health than non-religious people;

*these benefits can often be achieved if the practices are followed by non-religious people (it’s just that they generally are not);

*disbelieving doesn’t make things worse, it just generally results in people not doing the practices that make things better.

In their book How God Changes Your Brain: Breakthrough Findings from a Leading Neuroscientist, pp 3-6, Newberg & Waldman describe many of the positives of religious belief and practice (too long to quote) and also say:

Then on p149, Newberg & Waldman refer to “hundreds of medical, neurological, psychological and sociological studies on religion” and write:

I think that my summaries, within the limits of a blog post and comments, fairly reflect what Newberg says. And your negative comments generally do not reflect the research.

Your negative view of religious belief and believers may reflect your own experience, but it doesn’t reflect mine, nor does it reflect the research findings. The nasty effects of religion are the exception, according to Newberg, not the norm.

Research is done to give us better information than our intuitions and prejudices. I’m not sure why anyone wouldn’t want to be informed by the evidence.

But it seems we have reached an impasse. I have outlined the research as well as I am able to at this time, and your comments have helped me clarify some matters, and to correct some poor expression in my post, which is good, thanks. But I’m not sure I can elucidate any more.

Let’s leave it there, shall we?

As you wish….

I understand your position that complexity is unrelated to God, but there has to be some way that we can determine whether eternal beings are probable or not.

If we can’t use complexity to determine probability of un-caused phenomena existing, then I wonder what we could use…

If I were to propose that eternal, invisible demons exist shouldn’t there be some way for us to measure the probability of this claim? What if I then claimed that these demons were capable of creating matter and energy? Would that make them more or less probable? What about space and time as well?

If these eternal demons help us explain the origin of the universe does that make them more probable? I don’t think so.

It appears to me that human ideas about gods have evolved over time and that our current ideas about god are a reflection of what we are currently capable of imagining. We used to think gods existed in the sea and in the winds, then we thought gods existed way up in the sky looking down at us, then we decided that a single god was superior to multiple gods, then we decided that God had to be timeless and infinite and now he is a mind with no body that is also conscious and all-powerful. Could this be a reflection of what we as humans have been able to dream up? It certainly makes me wonder.

Hi Dave,

I think that the rather theoretical and abstract issue of complexity is not a good way to decide these questions, for reasons I have given, and I think there are many better ways. If a creator God exists and is worth knowing, I think he would leave some trace, give us some revelation. And I think he plausibly has done so.

1. The universe and human life within it seem to me to give us plenty of clues.

* If there’s a creative God, we might expect to find an orderly universe, well-designed to make likely the otherwise unlikely occurrence of human life – whereas if there was no God, it is hard to see how a universe could start, and even harder to see how it could be the one in a zillion universe that allows us to evolve.

*Likewise, if there’s a creator God, we might expect him to create beings like him – loving, rational, choosing, conscious and with a moral sense – but if materialism is true, it seems almost impossible to explain any of that, and many atheists deny much of it.

* And yet, there is much evil in the world – how do we explain that if a good God exists?

2. I think God gives us some very direct revelatory clues:

* There is very good evidence from secular historians that Jesus really lived and did and said many of the things said of him in the New Testament – enough for me to draw a positive conclusion about him revealing God to us.

* Many, many people have had their lives turned around by God’s apparent direct action in their lives. Surveys indicate that upwards of 300 million christians believe they have experienced a miraculous healing or observed one. I can believe that many of the stories are imagination, but all of them???

* And yet, God seems hidden to many people – how do we explain that?

These are the things I think we need to check out if we want to know God. My conclusion is that there is some evidence against God’s existence, but more in favour. So I conclude that God is probable, but not certain.

Well, perhaps not unless we define them a little more. We define God by being a powerful creator, etc, and look for evidence of a powerful creator, so if we define a demon as an evil being of limited power, we could test this hypothesis in the same way – look to see if a demon has left evidence of its actions in the world or in human life.

Yes, that might be true, or it might not. And even if we did dream God up, could he be true nevertheless? Only the evidence can tell us.