Steven and I have been discussing the Richard Dawkins vs William Lane Craig fracas on his blog Think That Through. At one point we referenced the ethical views of Peter Singer, and Steven suggested I do a critique of Peter Singer’s views on infanticide.

This is not something I have studied a great deal, but I thought it worth finding out more and coming to a view. Here’s a first assessment.

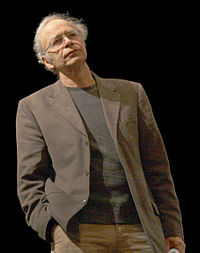

Peter Singer

Peter is an Aussie philosopher and ethicist currently working in the US. He is an atheist whose ethics are based on utilitarianism – which (more or less) says that an ethical decision will maximise happiness and minimise unhappiness. Singer supports preference utilitarianism which seeks to maximise personal interests or preferences. He has probably been more rigorous or brave in his ethical thinking than many others, coming to conclusions that allow abortion and even infanticide in some circumstances, and elevate some animal species to a similar status as humans (if they can be regarded as ‘persons’ – see below).

In praise of Singer

I disagree with many of these ethical conclusions, but before I discuss why, it is fair to give praise where it is deserved. Singer has shown himself to be a compassionate man in many ways, most notably in his advocacy and giving on behalf of the world’s poor. (This is something I intend to return to later.) I do not wish to paint him as a ‘monster’.

Singer and infanticide

Peter argues (see Practical Ethics and his own summary of his views in FAQ) that there is a distinction between humans (the animal species) and persons (conscious, rational, purposive beings, who are “capable of anticipating the future, of having wants and desires for the future”). Thus one of the ‘higher’ animals (say a chimpanzee) may be a person, whereas a newborn baby may not yet be.

From this definition and his utilitarianism, it is possible to see how Singer reaches his conclusions about abortion, infanticide and euthanasia. It is wrong, he considers, to kill any person who meets four requirements: (1) rational and self conscious over a period of time, (2) with desires and plans, (3) wants to live, and (4) is autonomous. A newborn baby fails to meet all of these requirements, and so can be considered a non-person. This doesn’t mean, in Singer’s view, that it is necessarily acceptable to kill babies, but rather that they have less of a claim to life than an older human who is clearly a ‘person’.

Thus, if there are reasons why the happiness of other humans would be increased by killing the baby (e.g. if the baby is disabled and would impose strain on the parents), it would then be permissible to end the life.

A brief assessment

Atheism and utilitarianism

Most atheists believe that humans and human societies have evolved through natural selection, without any intervention by a God. Societies have evolved ethics (it is often believed) that lead to better survival chances for that society. On this basis, ethics are subjective – each society may develop different ethics and there is no criteria to say one is ‘right’ and the other is ‘wrong’. Biologist Professor William Provine said: “Naturalistic evolution has clear consequences …. no ultimate foundation for ethics exists…”

Singer believes that ethics can be determined rationally via utilitarianism. However his ethic doesn’t really explain some crucial questions:

- Why should I follow a utilitarian ethic if I think I can improve my life by adopting a different course? The St James Ethics Centre in Sydney defines says ‘Ethics is about answering the question “What ought I to do?”’. On this definition, utilitarianism is not even an ethic because it doesn’t offer a reason to think we ‘ought’ to adopt it.

- It could be argued that if ethics are simply what helps survival of the individual or society, utilitarianism need only be applied at that level, and effectively becomes selfish, and able to justify genocide, rape, etc if they benefit the individual or society.

- Singer’s utilitarian ethics require arbitrary decisions. If killing a newborn baby is justified because it benefits a larger number of adult ‘persons’, why cannot the same apply to killing an adult if it benefits many others? Where do we draw the line? For example, when discussing infanticide, Singer says: “Most parents, fortunately, love their children and would be horrified by the idea of killing it. And that’s a good thing, of course.” But it seems that his idea of a “good thing” comes from outside his utilitarianism.

- It is well-known that utilitarianism struggles to define the benefits and recipients that should be assessed. This is particularly a problem in assessing environmental impacts which may occur far into the future, a problem Singer has recently acknowledged (in the new edition of Practical Ethics):

I have found myself unable to maintain with any confidence that the position I took in the previous edition – based solely on preference utilitarianism – offers a satisfactory answer to these quandaries.

So it seems to me that Singer’s ethics are a logical outcome of his atheism, but they have some serious inconsistencies and difficulties. It seems that he depends on some common human ethical intuitions to prop up his utilitarianism. There must be a better way, and he is now apparently considering a form of objective ethics that relies on some moral intuitions being correct.

Human intuition

Most people today would react to Peter’s views with horror. It is true that infanticide was practiced in many ancient societies, including the sophisticated Greek, Roman, Japanese and Chinese cultures, but most people would think we have made ethical progress since those days.

Human intuition may not be infallible, but I don’t believe it should be ignored either. Our natural feeling of abhorrence for pedophilia, infanticide or genocide cannot be easily ignored, and they may tell us something important. It is worth noting that utilitarianism relies on this same unprovable intuition when it says we should seek to benefit other people.

So we have a dilemma. Most of us would feel that Singer is wrong about infanticide, yet it is a logical corollary of atheism. To resolve the dilemma, we have to either re-think atheism (this is the basis of the moral argument for the existence of God – see How do we know right and wrong?), or re-think our repugnance at infanticide (in which case we will undercut the basis of utilitarianism).

A christian ethic

As a christian, I believe in a moral God who created a universe where ethics and rationality are objectively real, and in which conscious autonomous human beings could enjoy a rational and ethical life. Actions may be unethical not just because of their effects on others (as in utilitarianism), but their effects on us. God wants us to participate in his life, and grow to be as much like him as possible, and some actions work against that.

Christian ethics are objective. Jesus taught that the basis of all ethics is the simple command to love God and love our fellow humans – not all that different to utilitarianism, but different enough, and with a completely different purpose, to lead us to become more God-like. And much more in tune with the human race’s ethical intuitions than utilitarianism is.

In christian ethics, all things created by God have value – thus the environment is worth protecting. Living sentient things have value and can feel pain, so we should seek what protects them and harms them as little as possible. Human beings are made to be like God (i.e. conscious, rational, ethical, able to make choices that change things, able to be aware of God) and thus have greater value, and are more worthy of love and protection from harm. Those humans less able to care for themselves deserve special support and protection, because that is how God behaves towards us (in this protection of vulnerable and disabled babies, christian ethics are quite the opposite of utilitarianism).

Thus for the christian, infanticide is not acceptable except in exceptional circumstances. Babies are creations of God, made in his image even if they have not yet attained their full rationality, consciousness or volition; vulnerable and deserving of special protection. Of course there are still difficulties with this view – all views face difficulties in defining when in the process of conception, gestation, birth and life a human life and value commence – but it conforms to our intuitions and leads to a more humane and caring society.

While Singer is an atheist, he has admitted recently that he has some regrets that he cannot believe in God because that is the only way to provide a complete answer to the question, why act morally?

Summing up

Singer has attempted to develop an ethic from his atheistic/naturalistic beliefs, and there is much that is admirable in his thinking. But it leads to some outcomes that we intuitively feel are repugnant, including the possible killing of vulnerable and defenceless babies because a utilitarian calculation shows that this is “best”. He is now re-considering.

All this is contrary to our best human intuitions that the vulnerable and defenceless deserve special care and protection, and that it is noble and heroic to go beyond a utilitarian calculation to save or defend a life. Christian ethics provide a basis for these intuitions that Singer’s utilitarianism cannot provide – we are created to be like God and to become more and more like him in our grace and care towards those less able to care for themselves.

No ethical system can be ‘proved’ to be ‘right’ but I believe that utilitarianism diminishes our humanity whereas christian ethics ennoble us. I feel this is a strong argument for the value of christian ethics and the truth of the existence of God.

[…] But sometimes the artificial intelligence goes awry. My favourite was a comment on my post on Peter Singer and infanticide: I want to talk about this page with my […]