Journalist Christopher Hitchens said that religion poisons everything. Philosopher AC Grayling asked whether Christianity had brought any [positive] innovation to the world.

Historical author Tom Holland accepted Grayling’s challenge. While Tom is not a believer, he sees some very positives aspects of western culture that come from its Christian roots. His 2019 book Dominion develops this observation.

A sad and sorry record

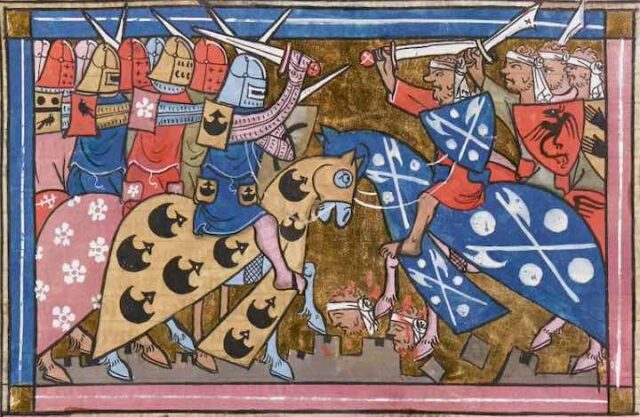

Let’s admit from the start that there are many actions done in the name of Christianity that have been far from Jesus’ teachings on love, non-violence and care for the vulnerable: the crusades, colonialism, some wars (though not as many as you might think), sexual abuse and power struggles in the church, racism and sexism, persecution of minorities such as Jews, queers and dissenters, and more.

We can question the genuineness of the faith of some of the perpetrators. We can note that similar behaviour can be attributed to non Christians also. But we can’t deny that these evils happened, and they shouldn’t have happened if people were following Jesus’ teachings.

But there is another side to the story.

Tom Holland’s five huge positives

Tom is a prolific historical author and broadcaster who has mainly researched and written about the classical period of ancient Greece and Rome. After initially being excited by the classical age, he was struck by how “foreign” and repugnant that period was to him.

It was brutal, with little respect for human life. Caesar was reputed to have killed a million Gauls and enslaved another million (huge numbers given the populations in those days), and was admired for it.

And Roman sexual ethics were abusive. Around the time he was writing Dominion, the Harvey Weinstein sexual abuse scandal hit the front pages. Holland comments that Weinstein’s use of his position of power to sexually abuse women wouldn’t have been scandalous in ancient Rome, that was what powerful men did. But that has all changed now.

Sexual ethics

Sexual ethics in ancient Rome allowed powerful men to exert abusive power over men and women, and to easily divorce and re-marry. In contrast, Holland argues that the Christian revolution is largely responsible for

- The dignity of women: Christian teaching on monogamy, equality in marriage, sexual ethics that applied to both men and women, and restrictions on divorce, all raised the status of women from what they had been in the Roman Empire and elsewhere. Of course patriarchy continues to exist within and outside Christianity, but Christianity certainly was apart of the move towards greater gender equality.

- The human body is not a commodity. In particular, women should not be treated as objects for male pleasure, as the #MeToo movement highglighted.

- These factors helped develop the idea of monogamy and life-long marriage within Christian ethics, an ideal which persists, imperfectly, in modern culture.

- The idea of sexuality as part of our identity: in Roman culture, a man could choose to have sex with men or women as he wished, without affecting his identity as a male. But Christianity tended to classify sins according to internal motivations and human nature rather than simply actions. This was a contributing factor to the modern understanding of same sex attraction as being part of a person’s identity, and therefore not something that the person has significant choice over. This is important for many queer people, although some queer theorists prefer to see identity as more fluid.

The sanctity of life

In many ancient Mesopotamian cultures, humans were created as servants or slaves for the gods, to do the work the gods were tired of doing. But in Christian and Jewish traditions, God made people “in his image”. They were to serve him as priests rather than as slaves.

The modern view of universal human rights and the sanctity of life owe a lot to this Judeo-Christian view of humans made in God’s image and therefore having high value. While there has been brutality and violence throughout the Christian era, we rightly regard it as deeply wrong in a way that pre-Christian societies were less likely to do.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights would be less likely without Christian ethics in Europe.

Values are universal

Different cultures develop their ethics in different ways. An evolutionary explanation for ethics asserts that these ethics are not objectively right or wrong, but are whatever evolves and works in that situation – “culturally contingent”.

But most of us don’t see it that way. Some things really are right and other things really are wrong. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights is understood to be universal, that is, right everywhere.

Tom Holland argues that this belief in universal ethics which we commonly share is in fact the product of Christian thinking.

Secularism

This one was surprising to me. The medieval church had political power as well as religious authority, so I expected secularism to be opposed by Christianity. But it isn’t that simple.

Holland tells the story of Pope Gregory (formerly named Hildebrand) in the 11th century. Gregory was a reformer, who recognised the corruption and compromise in the church. He felt the church needed to be “washed clean from the grubby hands of emperors”. The church needed to be holy and pure and separate from the “secular”, which was fallen and sinful.

This started process of reform that continued sporadically in the church, and set up the secular-sacred dichotomy. The separation of church and state in the US and elsewhere is based on this idea.

Questioning power

Too often in the world, the powerful win whether they are “right” or not. In Latin, “Rex Lex”, the King is the law and does what he chooses. Of course the alternative is “Lex Rex”, the Law is king, and no-one is above the law.

But Jesus’ teachings subvert this power game by saying that those who want to be great should be willing to serve rather than rule (Mark 10:42-44). The cross in Christianity isn’t defeat but victory.

And so, in counterpoint to the brutality and violence that seems endemic in human societies, and in which the church has often been complicit, there is the revolutionary Christian belief that it is better to suffer than to inflict suffering. Power corrupts and needs to be used very cautiously. And it follows that the weak deserve special care and, as Nelson Mandela showed, forgiveness is powerful.

Unfortunately it remains true that too few Christians understand this ethic, and sometimes others like Mahatma Gandhi understood and practiced it better. Nevertheless, passive resistance, non-violent protest, and curbing the powerful, are radical ideas that have come to us from Jesus.

It’s so familiar it isn’t obvious?

So, Holland argues, we are so saturated in Christian concepts and assumptions, most of us have no idea of their origins. He says so much of western thinking is either a development from, or a reaction against, the teachings of Jesus and Paul.

But is it that simple?

Not everyone agrees with Holland of course. Critics argue that:

- Many of the Christian values he mentions can be found elsewhere too.

- It is simplistic to think that Christianity is the sole source of our western ethics. Other factors are important too.

- His thinking may explain much in western (European) culture, but ignores other parts of the world, especially Eastern religions.

Holland has been criticised as an apologist for Christianity, but he makes no claim to Christian or theistic belief. Rather he says that his ethics are Christian, because he realises or believes that his ethical values are a result of Christian thinking.

Nevertheless, this historical observation can form the basis of a moral argument for God.

One non-Christian author, Terry Eagleton, makes the point that “when we condemn the moral obscenities committed in the name of Christ, it is hard to do so without implicitly invoking his own teaching”.

Or as another reviewer (Omar Ali) concluded: “if you do NOT agree with this thesis you should especially read the book to see how well your preferred theory stands up against a well written Christian version. If he is wrong, why is he wrong?”

Personally ….

…. I find Holland well spoken, smart and easy to listen to. It doesn’t concern me whether he is totally right in his thesis, or only partly right. Whatever, there is a lot of keen observation and truth in what he says.

His ideas aren’t a Christian apologetic, but they do offer facts that make Christian belief more attractive or at least palatable. Ethics are tricky. Deny the “rightness” of human rights and the “wrongness” of genocide and sexual abuse, and you may sound like a psychopath. Accept these values as true and you may have to explain how they can be true. Belief in a moral God is one solution to the dilemma.

If Holland is broadly correct, the moral argument for God is strengthened. He himself says he’s lost his faith in liberalism (i.e. secular humanism} and finds himself drawn towards Christian ethics and asking himself whether that is enough reason to believe in the supernatural aspects of Christianity which he currently finds difficult to believe.

I can relate to that. I think it is good to ponder the question, how do we know right and wrong? I think the moral argument is powerful. I think the issues he raises are some of the of questions that can reveal truth to us.

References

- The Power and the Glory. Print interview with Tom Holland, High Profiles, 2020.

- Video interview with Tom Holland, Leadership Conference, 2024.

- Review: Tom Holland: Dominion, the Making of the Western Mind. Tim O’Neill, History for Atheists, 2020. This page includes a link to a discussion between Tom Holland and AC Grayling.

- Getting back to the garden – Tom Holland’s Dominion. In That Howling Infinite, 2023. This reference includes copies of reviews of Holland’s book by Barney Zwartz and Terry Eagleton.

- Book Review: Dominion, by Tom Holland. Omar Ali, Brown Pundits, 2020.

Top graphic: 14th-century miniature of the Second Crusade battle from the Estoire d’Eracles (a French translation of a history of the period 630 to 1184, by William of Tyre, considered the greatest chronicler of the crusades), in Wikipedia. Photo of Tom Holland taken from the Leadership Conference video.