Most people agree that we cannot answer the question, is there a God? with a clear proof, either way. So most arguments for or against the existence of God start with observable features of our world, and try to show that these are compatible with the belief we ourselves hold, but incompatible with the opposite belief.

I’ve had some recent discussions that suggest to me that our human experience of free will is a strong argument against atheism.

Atheism, naturalism, materialism and free will

Atheists don’t believe in God, and most of them don’t believe in anything supernatural. In other words, almost all atheists are naturalists. And most naturalists believe the natural world is composed only of the physical or material things we are familiar with – matter and energy.

So in this post I’m going to take it that most atheists are materialists (or physicalists), although I know there are a few that are not.

It seems that most atheists therefore don’t believe we have free will. Famous biologist Francis Crick said that humans, including our supposedly free will, “are in fact no more than the behaviour of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules”. Other atheists like philosopher Daniel Dennett and neuroscientist Sam Harris support this conclusion.

And with good reason. If the world is only physical, then only physical events can cause other physical events. And physical events are governed, or described, by laws that are generally well understood. If a scientist knows enough about a particular situation, she can in principle predict the next stage using known laws.

So the electrical and chemical processes in our brains are also described and controlled by physical laws. And those processes, if materialism is true, are all there is to you and to me, as Francis Crick said. There is no mind, no “us”, apart from the processes. So there is no way “I” can interrupt those processes, because I am those processes.

So it seems that atheism and naturalism lead logically to determinism and the conclusion that we have no freedom to choose. (There is a view that re-defines free will and says that stripped down free will is compatible with determinism, but I am talking about what philosophers call libertarian free will, which is what most of us mean, and that certainly isn’t compatible with determinism.)

Logic and brain processes

If the physical is all there is, our brain processes, and therefore our thinking, are physical. That is, causes produce effects according to known physical laws. A neuron passes information across a synapse to another neuron, which responds in a way determined by the laws of physics. This cause-effect processing is the basis of all our thinking. And our thinking is determined by these processes.

On the other hand, logic is based on ground-consequence relationships. Our beliefs are made up of every opinion we hold, and if a belief is rational, it is a consequence of the assumptions or premises we start with; and the premises are the grounds of the conclusions. For example, I hear that a politician has a certain policy (ground) so I form the belief I will vote for him (consequence). An atheist might see the suffering in the world (ground) and so form the belief that no God exists (consequence).

So to think logically, we have to be able to “see” that a consequence logically follows from the grounds we began with, and then be free to choose our beliefs accordingly.

This straightaway raises a problem for the atheist, for if materialism is true, our brains work by determined cause-effect processes while logic requires ground-consequence processes and choice. The two are different. So at first glance, it might appear that our brains cannot do logic at all if determinism and atheism are true.

How can cause-effect brains do ground-consequence logic?

Since our brains are the result of evolution and natural selection, the obvious answer is that natural selection has “taught” our brain’s cause-effect processes to produce ground-consequence logic. Daniel Dennett says of our brains: “syntactic engines can be designed to track truth, and this is just what evolution has done.”

A computer is programmed so that its physically determined electrical processes can produce logical outcomes. So, it is argued, natural selection can lead to physically-determined brain processes producing logical outcomes just like a computer can do. Of course the human brain is more complex than a computer, a computer doesn’t, as far as we know, have any beliefs, and (for the atheist at least) the brain isn’t designed by a designer, but the analogy offers some hope of resolving the dilemma.

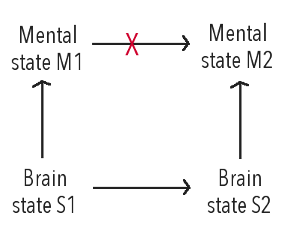

We need to be clear what is being claimed here. Brain state S1 leads by physical laws at work in the brain to state S2. Each state has an associated mental state, M1 and M2, but M1 does not produce M2, because M2 is produced via the physical cause and effect processes between S1 and S2. But, it is claimed, if natural selection has done its work, the brain has evolved so that M1 logically implies M2 even though M2 isn’t the result of logic. Thus, like a computer, the brain has come to a logical conclusion even though it hasn’t used logic, just physical laws.

Can natural selection do this?

A computer can use cause-effect electrical processes to produce logical outcomes because the hardware and software were designed to achieve this. But an atheist doesn’t believe that human brain processes were designed with an end in mind, it was all natural selection.

Now we know that natural selection favours capabilities that increase the likelihood of reproducing. Zebras that run fast live longer than slow zebras, and so reproduce more zebras with genes that enable fast running. And so the whole zebra population becomes faster. So for natural selection to produce a brain where cause-effect processes are capable of producing logical outcomes, that result has to lead to a greater probability of reproducing.

We can see that some cognitive faculties are helpful for surviving to reproduce. A zebra that reacts more quickly when a lion appears, or a suspicious sound is heard in long grass, will be more likely to survive to reproduce than one which reacts slowly.

But it doesn’t really matter whether the zebra believes that a lion is there. What matters for natural selection is that the zebra reacts quickly and lives to breed and pass on its genes. So it doesn’t require that the zebra reasons logically that a lion is there – stopping to reason would likely make the zebra less likely to survive. The best survival strategy will likely be to react on suspicion rather than take the risk of waiting until being sure.

So the best survival strategy will probably react more often when the belief is false than when it is true.

So we can see that many of our most important survival mechanisms don’t require any reasoning and don’t produce any beliefs – for example, all our unconscious bodily processes related to breathing, regulating our bodily temperature, etc. And others work just fine with false beliefs.

So natural selection works on our reactions and actions, and, if materialism is true, our reasoning processes and beliefs are simply by-products of natural selection.

But don’t beliefs affect behaviour?

If materialism is true, beliefs are the result of brain states, not their causes. Thus beliefs may appear not to directly influence behaviour, and many philosophers argue this. However, our brains receive inputs from the external world and respond to them, so it seems likely that beliefs can likewise have an impact on brain processes, by being part of the data which our brains use to make decisions.

But it is important to note that there is no choice in this, if materialism is true. The brain deals with these beliefs in a way determined by evolution. The beliefs may be true or not, but the brain will only recognise this if natural selection creates a brain able to discern right and wrong. But is this possible?

Does logic assist survival and reproduction?

It seems plausible. Being able to reason surely assists in survival and reproduction, doesn’t it? So wouldn’t the ability to reason develop and improve via natural selection?

There are many different levels of cognitive faculties. Some bacteria and amoeba are able to respond to their external environment and move to a more favourable location, but they can do little else. The small parrots in my backyard have learned to perch on our doorknob and call, and we will replenish their seed, but I don’t suppose they could add 4 + 4. A child of 9 can do that simple addition but probably cannot recognise Modus Ponens or calculate Bayes Theorem. Once in the long distant past I gained a Distinction in a university statistics exam, but I have no idea how anyone could prove Fermat’s Last Theorem. However just over 20 years ago Andrew Wiles solved the Theorem, the proof taking 129 pages, but I doubt there are many people in the entire world who could understand it.

So can natural selection be sufficient to explain Andrew Wiles’ mind, and higher cognition in general?

As we have seen, appropriate reactions are certainly necessary for survival. So the lower end of the scale of cognitive faculties can surely be explained by natural selection. And an ability to organise and choose between competing options might well make life more efficient. But as we go higher up the scale, surely the survival and reproduction benefits reduce and the impact of other factors becomes more important.

For example, psychologists sometimes classify thinking as either intuitive and analytical. The latter is more likely to employ logic, but isn’t always the most effective mode of thinking. In complex situations, or where a quick decision is required, intuitive thinking is generally more effective. An early homo sapiens who stopped to analyse the situation may not survive so well in Africa!

It is a sad but apparently often true fact that many women prefer a handsome, muscled Adonis to a clever logician, and many men are more attracted to a pretty face than to a PhD in economics. Of course, some people are both clever and attractive, but it is often not that way. So clever cognitive faculties may not lead to great reproductive success.

Higher cognition puts an additional load on the human system. We have larger energy requirements and a longer time between conception and full independence. These are negatives for natural selection which any advantages of cognition have to overcome.

And while a tool-making ape may well eat better and so live and reproduce better than one without that ability, it is hard to see how the ability to program a computer or prove Fermat’s last Theorem are going to help much in passing on genes.

So higher levels of cognition seem unlikely to supply any significant competitive advantage, and are likely to be outcompeted by other characteristics like speed and quick reactions (to flee predators), or strength and charisma (to fight off competing males, attract mates and so reproduce more).

Show me a model

I have discussed this with atheists and done a little reading, and so far I have seen assertions that higher cognition can arise via natural selection. But I haven’t yet seen anyone explain exactly how it would happen, and some philosophers who argue that it cannot.

I know of a post-doc researcher in the science of religion who uses computer models to explore this field. Surely it would then be possible to use a computer model to show how higher cognition could arise?

But until then, I think it is reasonable to doubt natural selection can lead to this, and to await some more complete explanation.

The problem of argumentation

But suppose that determinism is true and natural selection did indeed produce human brains. There are still, I think, negative implications here for atheism and materialism.

The problem arises when people disagree. That means our respective brains have used our determined cause-effect processes to arrive at different conclusions. Sometimes we can resolve these matters – for example, there is some piece of information that one person lacks, and when it is explained, the two former protagonists agree.

But sometimes two people can have the same information and yet still disagree – for example, questions of politics, the ethics of abortion or warfare, and the existence of God.

Now if we had choice, and if our brains could do ground-consequence reasoning, we could argue the matter out, testing each other’s assumptions, arguments and conclusions. We may not reach agreement, but we may at least expose some weaknesses in each others’ arguments and give each other food for thought.

But if materialism is true, then our brains don’t do ground-consequence reasoning, and our ability to do logic depends on how well our brain’s determined cause-effect processes can simulate logic. So if I disagree with you, it will be because my brain’s cause-effect processes don’t simulate ground-consequence reasoning in quite the same way as yours. And because our brain processes are determined, neither of us have any choice about this.

A computer example

We have seen that a computer can be used as an analogy for a brain (if materialism is true) – both work by determined cause-effect processes which have been programmed to simulate ground-consequence logic (the computer is programmed deliberately by a programmer, whereas the brain has, it is said, been programmed by natural selection). So let us imagine two computers programmed by different programmers communicating with each other.

It turns out that the two computers are given the same instructions but produce different results because of their different programming. They can try to argue which result is right, but they have different bases for their conclusions – they have been programmed differently – and each sees their conclusion as correct and the other’s as erroneous.

The computers are at an impasse. There is nothing they can do to resolve it. They have no ability to choose beyond the programming in their brains (CPUs). The only way it can be resolved is for the programmers to step in and each check the logic of their programs.

A depressing conclusion

I am suggesting that, if materialism is true, it is the same for brains. We can argue, and sometimes we will be able to convince the other person. But on more complex matters which require nuanced judgment, if materialism is true, there is no basis on which to show one view is more right than the other, and no ability to change. Our brains were programmed by natural selection, and won’t easily be changed.

It isn’t a palatable conclusion, for it seems to render all philosophical argument nugatory.

So when I ask the question on this blog, Is there a God?, and an atheist argues with my conclusion, they are assuming something about discussion and logic and truth that may be difficult to justify from their viewpoint.

It is little wonder that philosopher Thomas Nagel describes the naturalist explanation of rational thought as “laughably inadequate” while John Searle wrote:

In order to engage in rational decision making we have to presuppose free will.

Where do we go from here?

I think most of us know that this can’t be the truth. We really are able to think, evaluate and choose based on the merits of the argument. We get it wrong sometimes, sometimes our biases trip us up, and sometimes we try to address issues at the limit of our cognitive abilities (like I am doing here!). But overall, our conversations can be sensible and worthwhile.

So how does an atheist or materialist explain this dilemma? I have experienced three different responses.

1. There’s no problem

These ideas seem to me to show that, arguably, materialism, and hence atheism, is not compatible with the world we experience and the way we arrive at conclusions. This is a reason to consider materialism and atheism untrue. There are other reasons for and against belief in God, of course, but this is one argument that should be considered.

Some atheists shrug all this off. They don’t see any problem, it doesn’t concern them, and they don’t seem to have any answer.

I think this is a response they would criticise if a theist wasn’t interested in answering an atheist argument like the problem of evil. So I feel it isn’t adequate.

2. A misunderstanding of determinism

I have found many atheists have what seem to be inconsistent views about determinism and free will. When the nature of materialism is explained, they accept that our “choices” must be determined. But then they describe how they make choices in ways that suggest genuine freedom to choose (known as libertarian free will). I feel they are showing in their own reactions the dilemma for materialists – their philosophy tells them they can’t have free will, but their experience tells them they do.

I think the problem is compounded by compatibilists, who argue that free will can be compatible with determinism, but it is a truncated form of free will that doesn’t allow any real choice between alternatives. It seems to me like a trick to make materialists and determinists feel better by using freewill language but re-defining free will so it isn’t really free. This was apparent to me when I reviewed the discussions at a meeting of eminent naturalists a few years back.

3. Explanations

Of course thoughtful materialists have considered all these matters. Mostly they argue that natural selection can do the job and has produced brains that can reason well enough, though I haven’t seen any convincing detailed discussion of how this might occur, and how it might work out in discussion among people with different viewpoints on complex questions.

My discussion here is very preliminary, and I claim no philosophical expertise. But these are live issues between philosophers like Alvin Plantinga, JP Moreland, Thomas Nagel, David Chalmers and Victor Reppert, on one side, and John Searle, Daniel Dennett, Jerry Fodor and Michael Draper on the other side. I have read writings by all of these, but not comprehensively, and I will be looking to investigate further the ideas I’ve present here.

Clarification

While I think that this argument increases the probability that materialism is not true and hence that God exists, theism isn’t the only alternative to materialism. Thomas Nagel and (I think) David Chalmers, believe that there may be other options. In other words, atheism doesn’t necessarily entail materialism. But for atheists who are materialists, the argument seems to me to be challenging.

Constructive comments are welcome.

Photo: Pexels

Hi Eric,

I enjoyed reading this.

I agree that compatibilists redefine free will, although I think this redefinition is morally acceptable if compatibilists behave more ethically than hard determinists.

Hi Liam, thanks. “Morally acceptable” is surely important, but so also is “actually true”!

I’m not sure about compatibilists’ behaviour. In the reference I gave you on unethical behaviour accompanying a belief in determinism and disbelief in freewill, I’m not sure where compatibilism fits better.

Right, they are both important. However, I tend to view knowing the truth as only important to the extent that it improves people’s behavior.

I’m not sure where compatibilism fits better either.

“I tend to view knowing the truth as only important to the extent that it improves people’s behavior”

My problems with this are:

(1) How do we define “improves” without an objective ethic? Why should I give it the same meaning that you do?

(2) Is the statement “the truth is only important to the extent that it improves people’s behavior” actually true?

I think ethical theism and hard deterministic amoral naturalism both make logical sense (though the latter can’t be lived consistently), but I find everything in between to be logically inconsistent in some way. These questions are examples of where I see that inconsistency.

One other thing. I’ve been thinking that we’ve been having an interesting conversation, but I don’t know you beyond what you write. If you’d like to, why not send me an email using in the top menu, and I can get to know you a little better?

(1) I don’t think we can define “improves” in a mind-independent way without an objective ethic. When I say “improve people’s behavior,” all I mean is “changing people’s behaviors so that they are more aligned with my moral intuitions.”

(2) No, not in an objective sense. It is only true in the sense that it coheres with my moral intuitions.

In what ways would you say naturalism cannot be lived consistently?

I will email you!

I can understand this, but it seems to mean that you tie truth to ethics, and ethics are subjective, so truth becomes subjective. Surely any mathematician or scientist would have problems with that?

I don’t think many people can actually live without having thought processes and using language that infers freewill and objective ethics. I think you do it, as I’ve pointed out once or twice. And it turns out many psychologists agree, as I’ve noted here – Do humans have free will?, about halfway down under “the implications of determinism”.

I’m not sure what the best theory of truth is. I lean towards either a pragmatic or a deflationary theory of truth. I used to subscribe to the correspondence theory of truth, but then I stopped when I realized that truth cannot be defined in a non-circular way.

I agree that most people cannot live without having thought processes and using language that infers free will and objective ethics.

I’m not very familiar with those two theories, but I can’t feel they are very important. It seems that the deflationary theory is arguing about words, and rather meaningless, while the correspondence theory is just a way of defining the words and rather obvious. But I am probably a little naive there.

If we cannot live (generally) without thinking freewill exists, that surely is a prima facie reason to believe it is true? We judge the external world to be real because it seems to be real, it creates inconsistencies if we assume it is unreal (because our reasons for thinking it unreal are also unreal) and things work just fine if we think that. I think the same argument applies to freewill.

I think I agree with what you said about truth. I don’t think we’re discovering truth when we do ethics; I think we’re just stating which actions cohere with our moral intuitions and which do not.

I think that is a pragmatic reason to believe in free will, but not a philosophical reason to believe in free will.

That means you cannot say that the holocaust, torture, rape or pedophilia are wrong, they just don’t cohere with your moral intuitions. And if someone else thinks differently to you on those issues, that is nothing to criticise because the holocaust, torture, rape or pedophilia just cohere with their different moral intuitions.

Do you really believe that?

I would still say they are wrong in that they increase suffering and they conflict with the moral intuitions of most people. How are you defining the word “wrong?”

I think my view is similar to the view that Travis expressed in his moral ontology post:

“Under relativism I am able to say that the Nazis were wrong according to my intuitions and those of everybody I know, but I’m not making an absolute claim. Notice that the framing of the objection begs the question for moral realism, so it’s a bit of a trap that tries to force a response within the bounds of that assumption, pushing one to grapple with the intuition toward objective morality that was the focus of the prior discussion. That said, it seems to me that it’s also very reasonable to argue against the legitimacy of the Nazi program on the grounds of errant beliefs and an inconsistency with the moral nature of those who carried out the program. Furthermore, as noted above, there is nothing about relativism which entails inaction or ambivalence toward those with whom we disagree.”

https://measureoffaith.blog/2016/10/24/moral-ontology/

That would mean that, if the majority of people support Donald Trump even when he isn’t telling the truth, is ripping off charities and compromising US security, then he is still right because he’s NOT conflicting with the moral intuitions of the majority. Are you happy with that?

As something that is objectively unethical. It is as wrong as 1 + 1 = 3.

It still makes morality subjective and changeable. It still allows despots and destroyers to claim they are doing right and no-one can challenge them on that. I don’t think society can function like that, and I think most of us still act as if ethics are objective. I think it is a triumph of theory and presuppositions over reality. But I think probably we are not going to get any further on this just now.

G’day Eric,

Sorry for the late response; I didn’t get an email notifying me that you responded this time.

“That would mean that, if the majority of people support Donald Trump even when he isn’t telling the truth, is ripping off charities and compromising US security, then he is still right because he’s NOT conflicting with the moral intuitions of the majority. Are you happy with that?”

I’m not saying that an action is right as long as it does not conflict with most people’s moral intuitions. I’m just saying that an action conflicting with one’s moral intuitions is what makes one call something “wrong.” I would like to be an objective moral realist, but I don’t see any evidence for a mind-independent moral standard.

I’m not a huge fan of Trump, but I do like that he doesn’t support using taxpayer money to fund partial birth abortions.

“As something that is objectively unethical. It is as wrong as 1 + 1 = 3.”

My next question is how you are defining “unethical.” I don’t think “wrong” can be defined in a non-circular way unless it is related to one’s conscious experience. It doesn’t have to be defined in a non-circular way, as not all words are, but I think it makes the most sense to define it as “makes me feel uncomfortable.”

“It still makes morality subjective and changeable. It still allows despots and destroyers to claim they are doing right and no-one can challenge them on that. I don’t think society can function like that, and I think most of us still act as if ethics are objective. I think it is a triumph of theory and presuppositions over reality. But I think probably we are not going to get any further on this just now.”

I can still say that the behaviors of despots and destroyers conflict with the moral intuitions of most people. But I agree that most of us act as if ethics are objective.

Hi Liam,

I think “unethical” means contrary to what is truly right. Just like “false” means contrary to what truly is.

I think you only think this because you have already assumed moral relativism. If moral realism was true, then there is an objective standard of right and wrong (like most people intuitively feel), it’s just that we don’t seem to have the necessary cognitive or sense apparatus to detect it like we can detect the physical world.

Yes, I think that is all a moral relativist can say. But I think it is pretty weak compared to what we actually intuit. When I think of the holocaust or the recent destruction of Syria, or a recent car accident in Sydney where a drunk driver mowed down 6 or 7 kids and killed 4 of them, “that makes me feel uncomfortable” is way too weak. “That was evil” is closer to the mark.

Surely this is prima facie evidence that perhaps, maybe, moral realism is actually true, and there is more to the world than naturalism?

Hi Eric,

Eric: “I think “unethical” means contrary to what is truly right. Just like “false” means contrary to what truly is.”

How do you define “ethical” and “right”?

Eric: “Yes, I think that is all a moral relativist can say. But I think it is pretty weak compared to what we actually intuit. When I think of the holocaust or the recent destruction of Syria, or a recent car accident in Sydney where a drunk driver mowed down 6 or 7 kids and killed 4 of them, “that makes me feel uncomfortable” is way too weak. “That was evil” is closer to the mark.”

“Uncomfortable” probably isn’t the best word. “Makes me have an unpleasant feeling” might be a better phrase. This unpleasantness can be constituted by discomfort, anger, or disgust.

I would like to discuss abortion, if that’s OK with you. Would you mind stating your stance on abortion?

Eric: “Surely this is prima facie evidence that perhaps, maybe, moral realism is actually true, and there is more to the world than naturalism?”

Most people assume that their own moral intuitions are the correct moral intuitions, but the fact that people have such different moral intuitions (e.g. abortion) is evidence to me that morality is not objective.

I think we should answer these sorts of questions about ethical realities the same way we answer questions about physical realities – i.e. “ethical” and “right” are what conforms to ethical reality, just as what is real = what conforms to physical reality.

It is still, I think, a flimsy basis for ethics. We know in our guts some things really are wrong, but all we can say is that they give us an unpleasant feeling? In my view, no matter how little evidence I thought there was for God, I would think God-belief would be more compelling than saying our strong gut feelings about ethics are not really based on truth but just on how we happen to feel, and others don’t happen to feel.

Sure. I think it is a complex matter. Prima facie, it looks like it is taking a life, so I am broadly opposed to it on those grounds. But:

(1) I am not a woman nor in a position where I have to give advice or make a decision on abortion, so I would want to be careful not to pretend my view is expert or well thought through.

(2) I note that sometimes killing may be justified. I am generally a pacifist, but not doctrinaire about it, so perhaps sometimes abortions are ethical.

(3) I also note that there are apparently 4 times as many natural abortions (miscarriages) as there are human-induced abortions, so we have to factor that into our consideration. Is God OK with that? Shouldn’t we be concerned about that too?

(4) I am a christian and not everyone is, so I accept there are other views on this.

What do you think, and why did you ask?

Also possible, surely, is that morality is objective but we don’t have reliable moral faculties to see that? (Just as a blind person lacks the ability to see and understand colour.) Granted the sorry state of the world, I would say that the hypothesis of an ethical defect in the human race seems eminently believable!

For anyone following the discussion, the discussion is continued here:

https://reasonablydoubtful1.wordpress.com/2019/04/10/morality-is-subjective-but-it-might-as-well-be-objective/#comment-971