What should we make of the story of the Exodus in the Old Testament?

What should we make of the story of the Exodus in the Old Testament?

Two million people escape slavery in Egypt after a series of savage plagues, with God leading the way. They escape the pursuing Egyptian army by walking through the waters of the Red Sea, which God miraculously parts, then closes on the army drowning them all while the Israelites gloat.

God miraculously provides them with food and water in the desert, gives them his laws including the Ten Commandments engraved on stone, but only after killing 3,000 of them for worshiping an idol. God also sends other punishments for disobedience – fire, an earthquake and venomous snakes, but also helps the Israelites kill their enemies.

All in all it is a violent and supernatural story, but eventually the Israelites reach their destination, the Promised Land of Canaan.

The story is foundational for the Jews and important for christians. But many find it unbelievable. Some disbelieve in the supernatural, some have problems with the violence of a supposedly loving God, some cannot believe that 2 million people were involved. Some sceptics use the difficulties in the story to argue that the Bible is unhistoric and christian belief baseless.

These sceptics are supported by most historians and archaeologists, who say there is no evidence for the events portrayed.

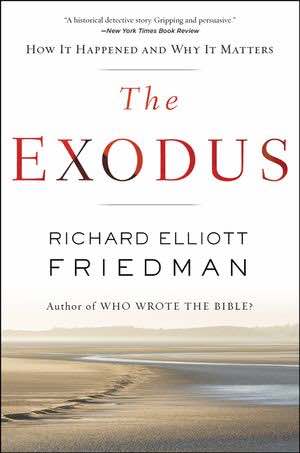

A new book by Richard Friedman takes a fresh look at the Exodus and charts a course between the extremes of scepticism and faith.

I was given this book as a Christmas present, and I have finished it already, so that gives you an idea that I found it absorbing and easy to read.

Friedman’s new idea

Friedman agrees with the other scholars who say the numbers are too great and the miraculous unbelievable. But instead of rejecting the story outright he argues that a smaller group did indeed escape from Egypt and travel to Canaan. He believes it is likely that Moses was a historical figure.

He gives reasons to believe that the Levites (the clan from which Jewish priests come) had a strong connection to Egypt, shown in:

- some of their names, which are Egyptian in origin,

- their religious practices (notably the tent of meeting and the ark of the covenant, which appear to copy elements of Egyptian religious practices), and

- the DNA of modern Kohanin (those Levites who descend from Moses’ brother Aaron) which is different to the rest of the Jews and other descendants of the ancient Canaanites.

He concludes that it was the Levites who made the journey, bringing some new religious and ethical ideas (monotheism and respect for aliens and slaves), unknown elsewhere in the Middle East at the time. When they reached Canaan, they joined with the Canaanites already there in the kingdoms of Judah and Israel and gradually transformed the Canaanite worship of the god El and his consort until it became worship of the only true God, Yahweh, creator of the world.

The Bible story can then be seen as a historical story that was embellished with legendary material to support the Israelites’ claim to the land and their understanding of their place in the world.

Is Friedman’s argument believable?

Friedman is a professor of Jewish Studies and presumably of Jewish descent. He may not be totally objective on this matter, and this sometimes shows in the later chapters of the book where he discusses how the Exodus brought two such important ideas (monotheism and care of the alien) to the world.

Nevertheless, he shows that many other scholars share his general view. The evidence he offers isn’t compelling, but it is suggestive, and seems to be a reasonable way to explain how the Exodus story came to be written.

We cannot be certain about events that happened (or didn’t happen) more than three millennia ago, but I feel his hypothesis is more probable than any other.

What does this say about the Bible?

His evidence will probably not please, or be convincing to, either conservative christians or sceptics. But I think it makes more believable a different view of the Bible from the reliable literal history of the conservative christians and the unbelievable legends of the sceptics.

As a christian, I have no trouble believing that the Bible is a record of God’s unfolding revelation to pagan peoples. Like a teacher or a parent he gradually refined and corrected their beliefs and ethics. They recorded their beliefs and stories, initially in the form of legends and “fictionalised history”, but gradually they began to write more accurate histories. Thus a story that is a legendary development of an originally true event seems likely to best describe the Exodus story.

An atheist, a Jew and a christian can all accept Friedman’s conclusions, but this would still leave many questions unanswered. How much of the story is historical and how much is legendary? Did all, or any, the miraculous events happen? How did the Levites come to their revolutionary understanding about monotheism and ethics? How much of the story can and should a christian accept just because it is in the Bible?

Worth a read

Friedman’s book is easy to read, and includes the occasional light-hearted comment. It has plenty of references to follow up if you are so inclined. I recommend it.

Read more about the Exodus

I have written up my assessment of the historicity of the Exodus in the light of this book, and a few others I have read, in Did Moses really lead 2 million people across the Red Sea and into Canaan?

I hope you check it out and get a few more details of the evidence.