The reliability and historical accuracy of the New Testament seems to always be of interest to both sceptics and believers alike.

It is easy to find newspapers and online websites with claims that some new discovery proves or disproves the New Testament, but the truth is actually a little more mundane. New discoveries are being made all the time, and these provide useful information on the New Testament text, but rarely merit sensational coverage.

Here are a few discoveries and conclusions that have come to light in recent years.

Why do we need textual studies?

The 27 documents that make up the New Testament were hand-written in Greek on perishable material that had a limited life. Copies were made, and copies of copies, and so on, a process that inevitably leads to copying errors. Most of the copies eventually wore out or were lost, so the New Testament we read today is a translation of the best copies now available.

Choosing which are the most accurate copies is a complex and expert task. You’d expect the most common surviving text, or the earliest, would most likely be the original, but of course other factors may change this conclusion. For example, sometimes experts can see reasons why a scribe may have accidently or deliberately changed the text he was copying, thus identifying which version was original.

It is natural that questions are asked about the reliability of this process, especially:

- How long after the events were the original documents written? The further removed from the events being reported, the more likely it is that the events haven’t been remembered accurately.

- Do we have sufficient early copies to do rigorous study? If there are few surviving manuscripts, or if they are late (and thus likely the result of multiple copying) we will have less confidence in conclusions about the text.

- Was the copying done accurately? Can we have confidence that what we read is what was originally written? This can be tested by examining the variations in the various copies that have survived.

1. How long after the events were the original documents written?

The earliest possible dates are shortly after Jesus’ death, and the latest possible date for each book is when we have the first surviving manuscript or the earliest mention in another document. But between those broad ranges there are widely varying conclusions. Some of the main factors influencing conclusions are:

- whether the author appears to know about the Roman destruction of the Jerusalem temple in 70 CE, a cataclysmic event for first century Jews;

- whether the issues addressed in the book appear to be more relevant to a particular time period; and

- how the book fits into the life of the supposed author.

For decades, the consensus conclusions have been:

- Paul’s “main” letters (the first 7-10): between 50 & 60 CE (other letters where Paul is named as author are considered by many scholars not to have been written by him).

- The four gospels: between 65 CE and 100 CE, with Mark probably the earliest, then Matthew, Luke (and Acts) and John.

- The remaining letters: between 70 CE and 120 CE.

Recent trends

In the last two decads a few scholars have suggested slightly earlier dates for some of the books.

- Almost 20 years ago, James Crossley and Maurice Casey argued for a much earlier date for Mark’s gospel, somewhere around 40 CE which would make it very close (within a decade) of Jesus’ death – which is very close by ancient standards. Casey also suggested an earlier date for Matthew (before 70 CE).

- It seems few other scholars were convinced by Crossley & Casey (see e.g. Mark Goodacre).

- More recently (2022) Jonathan Bernier did a complete review of the composition dates for all 27 New Testament books, the first such thorough review for half a century (Ref 2). He concluded most of the books should be dated earlier than the consensus, with Mark in the early 40’s (similar to Crossley and Casey), and most of the books prior to 70 CE.

- While most scholars still believe the gospels and non-Paul epistles were around 70 CE (Wikipedia) or shortly after (e.g. Bart Ehrman), a few scholars have welcomed Bernier’s conclusions (see e.g. James McGrath and Stanley Porter).

Whether the consensus changes slightly, particularly regarding the dates for Mark and Matthew, or not, the gaps between the events and writing are not large when compared to other writings from the period.

2. Do we have sufficient early copies to do rigorous study?

At first glance, the New Testament text compares extremely favourably with other documents of the time. Many more manuscripts, much closer to the writing date. Christian apologists have used this fact to claim a high degree of reliability of the New Testament text.

But it turns out it isn’t that simple.

A 2019 book by a bunch of textual scholars has examined these matters, seeking to try to avoid the extremes of enthusiastic apologists and critical sceptics. They found that information by many apologists was often unreliable, numbers have not been not up-to-date and comparisons of the New Testament with other writings have often been inconsistent.

Here are what seem to be safe factual assessments:

- There are currently over 5000 Greek New Testament manuscripts, many more than for any other ancient text.

- However most of the surviving NT manuscripts are late – only 7 from the second century and over 80% of the five thousand are from the second millennium.

- Few of the manuscripts (about 60 at present) are complete copies of the New Testament. Many of them are small fragments only. The earliest complete copies of books date to the beginning of the third century, whle the earliest complete New Testament, Codex Sinaiticus, dates to the fourth century.

- Fortunately for the history of Jesus, the gospels are well represented – more than 350 manuscripts dating from the first millennium. Almost the complete text of John can be found in manuscripts prior to the 4th century, but only about 20% of Mark can be found in manuscripts from that period.

Thus counting and assessing the number of manuscripts is complex, constantly changing as new manuscripts and fragments are found. Comparison with other ancient texts is therefore fraught with inaccuracy. Nevertheless, it remains true that there is much better manuscript evidence for the New Testament than for other ancient texts, and there are sufficient numbers to allow variants to be assessed.

Recent discoveries

Some documents are discovered but not analysed and translated for some time. So “recent” here means manuscripts whose text and dating have recently been made public.

Re-discovering an erased text

Parchment was valuable and sometimes hard to obtain in ancient times. So sometimes the text on an old parchment would be erased by scraping or washing, and new text writton. This is known as a palimpsest.

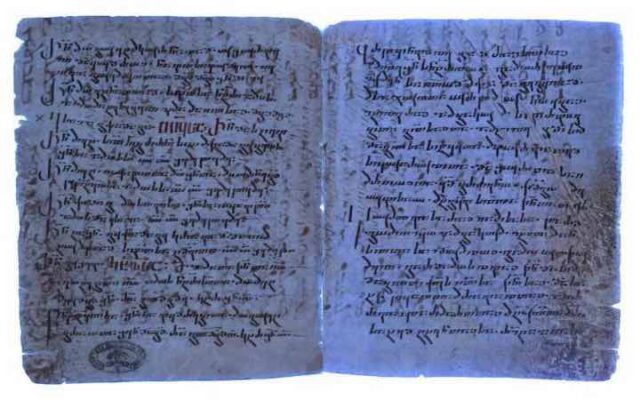

But the text wouldn’t actually be completely erased. Some traces of ink or indentation remain, though often not visible to the human eye. However modern imaging techniques can often recover the text. One technique is to view the document under ultraviolet light, which makes the underlying text easier to read.

Palimpsests are not always recognised immediately. And so it was with a 1,750 year old fragment in the Vatican Library. A researcher discovered it was a palimpsest, in which a scribe in Palestine had written over an old copy of the gospels. This fragment contains a short section of Matthew’s gospel, written in a third century translation into the Old Syriac language. This copy of the gospels was made in the 6th century and over-written in about the 10th century.

This fragment, shown above under ultraviolet light, added some explanatory words to the original Greek text, and is valuable in understanding the development of Syriac translations.

Ancient manuscript of Acts

A codex (an ancient manuscript book) in a New York library since 1962 couldn’t be opened and read because it had been sealed and damaged by water and fire. But in 2018 X-Ray technology was used to “read” the inside contents of the manuscript, which proved to be the book of Acts, written in Coptic, a language of ancient Egypt.

This version of the book of Acts contained only a few variations from the generally accepted Coptic text – the “new text differs from the published texts only in a few individual spellings”.

Sayings of Jesus

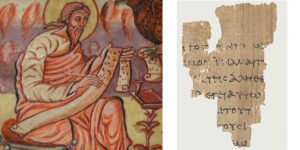

More than a century ago, half a million papyri fragments were discovered in ancient trash heaps at Oxyrhynchus in Egypt. The fragments included a wide variety of texts, from sections of the New Testament to “every aspect of ancient life—commerce, friendship, lawsuits, romantic relationships, and shopping habits”.

Sorting, identifying, and publishing these texts is an enormous task, and so far more than five thousand have been published. Recently (August 2023) some more were published by the Egypt Exploration Society, including a couple of small fragments of a manuscript (P.Oxy. 5575) containing sayings of Jesus.

The fragment is of interest because it has been dated to the second century, making it one of the earliest texts containing Jesus’ words. It appears not to be from one of the gospels, but rather has words similar to the sermon on the mount recorded in Matthew and Luke, and also in the non-Biblical gospel of Thomas.

This fragment thus probably doesn’t provide evidence of the copying of the gospels, but may provide insights into the process in which saying of Jesus were written down and circulated in the very early days of Christianity, forming sources which the gospel writers may have used.

Was the copying done accurately?

The skill of the copyists

Many people in the ancient world weren’t literate, and many others didn’t have the ability to copy a manuscript in a readable writing style. Scribes were commonly used, both for literature and for everyday texts such as accounts, legal documents, letters, etc.

There is a common view that the people who copied the various documents that ended up in the New Testament were poor scribes. However recent work has shown that this is rarely the case, at least where it can be checked. This is shown by two factors:

- The quality of the writing: competent scribes can be recognised by the way they write, and two recent studies have concluded that “the vast majority of the Christian papyri were copied by trained scribes.” (Alan Mugridge, 2016, quoted in Ref 1, p139)

- The consistency of the writing: a competent scribe can write consistently for an extended time, so the quality of the text is as good at the end of a long document as it is at the beginning. Again, the Christian manuscripts mostly, though not always, show this consistency.

It is also known that scribes used various means to check their work – for example, the scribe or a supervisor checking and correcting the completed work. They also made marginal notes where there was uncertainty. So while errors and deliberate changes undoubtedly occurred (see next section), the New Testament copyists from the third cetury on were well trained and competent. Unfortunately we have very little evidence of copying in the late first century and second century.

Errors and differences

Scribes, no matter how competent, obviously made mistakes. Sometimes it was accidental human error. Other times the scribe chose to make a change, perhaps to make the text read more clearly, or to conform to some theological position, or because the scribe had several copies of the document and had to make a choice when they differed.

If we only had a few copies of each book, it would be difficult to know which of several variant readings should be preferred. But with many, many manuscripts and fragments, more errors and differences are found, but they can generally be identified and the most likely original text can be recovered.

So how accurate does this information show the copying to be?

There is no simple way to measure the accuracy of copying of the whole New Testament, because there are thousands of manuscripts and many variations, and there is no way to accurately count the number of variants or the total number of words across all the manuscripts. In all the known Greek New Testament manuscripts, it is estimated there are about half a million variant readings (Ref 1, p194) across millions of words. One sample count suggested a scribe might make an error, on average, every four or five hundred words copied, which is quite accurate, but it isn’t clear how representative this count is.

In the end, most numbers quoted are meaningless. Most variations are spelling or other minor errors that don’t make any difference to the meaning and can be easily identified and corrected. The best way to assess this question is to identify significant variations, that is, variations that make a difference to our understanding of history, doctrine or ethics.

This turns out to be very few. Textual scholars have been able to identify the oldest and most original text in most cases and eliminate scribal insertions. The number of “conjectures” (where the original meaning cannot be established) is reducing over time, from 18 in the Nestle-Aland text in 1927 to 2 in 2012.

Scholars say that the remaining uncertainties make no real difference to our understanding. However it is true that in the past, identification of some later additions to the text has led to a few significant changes to the established text.

The impact of recent discoveries

Recently discovered and published New Testament manuscripts, such as those mentioned above, show occasional variations, but rarely has this led to changes in the established text in recent years. However there do remain a number of places where a variant makes the exact meaning uncertain.

Conclusion

We can be confident that the text of the New Testament currently in use is very close to the text of the original writings, which in turn were written relatively soon (by historical standards) after the events they recount. The uncertainties may make it harder to believe in the inerrancy of scripture (a doctrine I don’t personally believe) but the history, doctrine and ethical teachings the New Testament contains are well established. It isn’t perfect but it is generally reliable.

Recent discoveries tend to support rather than throw doubt on this conclusion.

Of course whether the story the New Testament tells is true is another question!

References

- Myths and Mistakes in New Testament Textual Criticism. Elijah Hixson & Peter Gurry (eds), 2019. My review of this book: How accurate is the text of the New Testament?

- Rethinking the Dates of the New Testament. Jonathan Bernier, 2022. My review of this book: When was the New Testament written?

- What’s the Big Deal about a New Papyrus with Sayings of Jesus? Michael Holmes, Text & Canon Institute, Phoenix Seminary, Sept 2023.

- New Testament: Fragment of 1750-year-old Translation Discovered. Austrian Academy of Sciences, APril 2023.

- Acts of the Apostles. The Morgan Library & Museum.

- Preserving Ancient New Testament Manuscripts for a Modern World. The Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts.

Main graphic: Fragment of 3rd century Syriac New Testament shown under ultraviolet light (Vatican Library, taken from Phys.org). This picture was included in a press release from the Austrian Academy of Sciences (Copyright: Vatican Library).

Second graphic: One side of the two-sided P.Oxy.5575, by Ardon Bar-Hama and taken from Text & Canon Institute, Phoenix Seminary.

Hi, good post overall!

“most scholars still believe the gospels and non-Paul epistles were post 70”

This is not true for Mark. Most American scholars think Mark was after 70. Well, maybe, if you ignore conservative scholars working at seminaries and religious universities. But most European scholars like Hengel, Focant, Guelich and the late Robinson think Mark wrote between 60 and 70.

Hi Pierre, thanks for this info. I’ll check out the people you reference and maybe change the wording a little.

Hi Eric. Vic here writing on Margs phone.

I generally agree on your assessment, but as one deeply interested in Bart Ehrmans pov,

I question one of your conclusions, that the history and theology are well attested.

Whilst this is true of many aspects, it is not viable re the doctrine of the Trinity. This is not a textual transmission issue so much as it relates to the changing views of Jesus from his death through to the conclusions of the Trinitarian debate.

I believe that some of his followers put words in Jesus mouth to affirm his god status.

I do not disagree with the doctrine but question whether some statements were actually made by Jesus.

I also think that scribes changed other words.

In particular, the history of the pericope adulterate is very instrumental in this debate.

Any thoughts?

Vic

That some words were put in Jesus’ mouth is generally recognised. Such was the method of ancient historians! Less credible is that this was to affirm his god status. The view that Jesus had a superhuman status as a divine being was rather early, the view that he was God in a sense is considerably later! Divine being didn’t imply equal with God in Second Temple Judaism! John clearly saw Jesus as divine in a way, but what it meant to him precisely is not so clear.

It’s recognised that the language of the Pericope Adulterae has characteristally Lukan elements; so much that it has been a serious theory in the past that it was original to the authentic version of Luke, but soon removed yet eventually inserted into John! (I do not hold this theory. I do believe that the core of the pericope reliably dates to the first century.)

Hello again, Pierre.

I have done a bit more checking, and find it is difficult to know how to “correct” this comment.

I based my conclusion partly on Bart Ehrman (in the link in the post) where he says “New Testament scholars are virtually unified in thinking that the Gospels of the New Testament began to appear after 70 CE. The major exceptions are conservative evangelicals who often date them earlier.”

But I have several times found Ehrman to be an unreliable source. He seems to overstate his conclusions and stigmatise anyone who disagrees with him as having religious motivations. So perhaps I should have been a little more careful.

There are certainly scholars who hold to a pre-70 CE date for Mark (Crossley, Casey, Bernier, Robinson, Hengel, Focant, Guelich, etc), and Wikipedia says a date around 70 CE.

So I have amended the post to say “around 70 CE or shortly after”.

Thanks again for your input.

Hi Vic, nice to hear from you and to have you reading my blog.

I agree with you about the doctrine of the Trinity. I think it is a human attempt to understand the unknowable, based on what are at best hints in the scriptures. I hold to it also, but very loosely. I think the divinity of Jesus is very clear in the NT, but much less clear in the gospels – one of the reasons to believe the synoptic gospel writers/compilers were reliable is that they DIDN’T add much clear evidence for Jesus’ divinity, even though Paul had written clearly about it earlier. John of course is different, but I don’t think he so much put words in Jesus’ mouth as blur the line between Jesus’ words and his own reflections.

My go-to person in all this is Larry Hurtado, who studied the subject extensively. He concluded that belief in Jesus’ divinity arose very quickly after the resurrection, as they found themselves worshiping Jesus alongside God, and had to understand the implications of that.

I was thinking more generally about “theology” – matters like the kingdom of God and Jesus’ place in it, the goodness of God, salvation, etc.

What is your particular interest in Bart Ehrman’s viewpoint? (Do you mean the “orthodox corruption of scripture”?)

Hi yegeman4, thanks for your interest and your comment.

I feel I am in partial agreement with you. I certainly agree that “Divine being didn’t imply equal with God in Second Temple Judaism!” But I believe Larry Hurtado has shown conclusively that “the view that he was God in a sense” was actually quite early. I would agree that the formulation of this belief was still in its infancy in the early days, but Hurtado has shown (I believe) that Jesus was worshiped alongside God from almost the very beginning.

I agree with you also that the story of Jesus, the woman and the accusing men is likely genuine and first century, although it almost certainly wasn’t in the original of John.