A couple of weeks back I posted some information on the surviving documentation for a number of ancient texts including the New Testament (Revised dates for ancient documents). Now, in the comments to that post, I have been asked some more questions about the New Testament documents.

So here’s the answers to those questions, as best I can know them.

Background

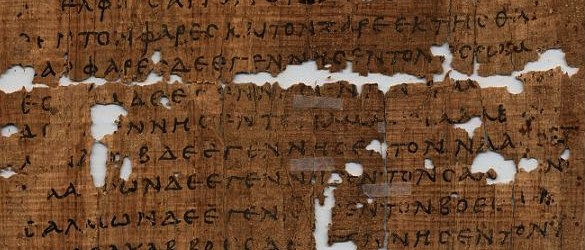

The original documents which make up the New Testament were written in the first century in Greek on papyrus, and copied for use by the early christians. Papyrus does not last all that well, so copies were made of the originals, copies of copies, and so on, until hand copying became unnecessary in the 16th century because of the printing press. None of the originals have survived and only a small percentage of these copies have been discovered.

For us to have confidence in the accuracy of the copying, we would like to have many copies as close as possible to the originals. The accuracy of the copying can be tested by checking how much variation there is in the various copies.

It turns out that there are many more surviving documents, and much earlier, than is the case for any other ancient texts.

What documents are usually listed?

Can you define ‘New Testament document” for the purpose of this article. Is this the number of hand written copies until the invention of the printing press?

5795 copies of part of the New Testament in the original Greek have been discovered. Many of these are only fragments (the earliest is dated about 125-130 CE), but some are complete books (earliest: about 200 CE) or even complete New Testaments (earliest: 4th century). These are the figures usually quoted. In addition, about 10,000 NT documents written in Latin and over 9,000 in other languages (Syriac, Slavic, Coptic, etc) have survived.

Dates of the surviving documents

is there any way to make a histogram of the number of documents as a function of the century in which it was written?

I have used the information in Wikipedia, which isn’t up-to-date (the total is listed there as 5197, well short of the current 5795), but the spread should be representative. The graph below shows that most of the copies date from the ninth century onwards.

Useful documents

Based on this information, how many documents out of the 5000+ are actually useful in textual criticism?

I would imagine all would be useful to some extent, though many would not make any difference on their own, but would simply add to the cumulative weight of evidence.

Documents can be useful in a variety of ways. Textual experts study not just what they conclude is the original text, but how that text and variations spread in space and time, in the form of a tree. This allows them to make informed assessments of which variation was “original”, based not simply on which has the most surviving texts, but which part of the tree is closest to the original.

Thus the wealth of copies of NT documents reveals variations in a way not possible for texts with fewer copies and allows statistical assessment and a real choice for experts, rather than having no options if there are few texts.

It is worth noting that there are very few significant textual variations – most are obvious mistakes, spelling errors which don’t change the meaning, etc. As I’ve recorded in The reliability of the New Testament text, Bart Ehrman’s Misquoting Jesus list a number of the most serious variations, the most important have which have been resolved in modern translations, while the remaining ones don’t seem to change anything significant.

Errors of estimate

Can you explain why dates for ancient manuscripts, or the actual authorship of NT books for that matter, are rarely if ever reported with a range of possible dates, uncertainty bars, or terminus dates?

Most sources I’ve read give some idea of the uncertainty, not always in the form of “uncertainty bars” (I think that would suggest an unrealistic level of precision), but certainly in the form of a range or use of the word “about” (generally in the form of the letter “c” = “circa”). This is the case for the Wikipedia listing.

The earliest New Testament copy

can we also discount, or at least diminish the importance of scraps, fragments, and otherwise incomplete documents from those useful for textual criticism? I am certain the document that Clay Jones reports as being from “AD130 or less” is the famous scrap from the Gospel of John that is so small as to be worthless for textual criticism.

As I’ve noted above, most smaller fragments add cumulative weight but don’t change much on their own, but I think P52, the fragment of John’s Gospel that is the earliest NT document we have, is very important.

A century ago, John was often dated to late second century, making it of little value in historical study of Jesus. But in the last century, that date has moved a century earlier, and I suggest this piece of papyrus has played a part in that – which gives it significant value.

Read more

I have written more on the NT text at Are the gospels historical? and The reliability of the New Testament text, and as a result of this brief investigation, I may amend those pages slightly. Thanks for prodding me.

Photo: Part of papyrus P1, a portion of Matthew’s gospel dated 250 CE (Wikipedia)