Archaeology can bring the past to life. It can allow us to see, not just read about, some aspects of life in the past. This can especially be of value to Christians seeking to understand Jesus better.

But the archaeology of the New Testament era in Israel can also be contentious. Christians can look for any confirmation of their faith, while sceptics can seek to undermine faith. Zionist Jews can seek to strengthen their claim to the land while Palestinians can try to undermine this.

But behind the arguments are the facts of archaeological discoveries. Here are some interesting discoveries, new and old.

Don’t expect too much!

No-one expects significant archaeological artefacts directly about Jesus. He minted no coins, he didn’t build a temple in his own honour, not was he a prominent public figure that would have a statue of him erected. As far as we know he didn’t write a book or send messages on papyrus or clay tablets that might later be discovered.

Very few ancient people left behind an archaeologial record. Professor Bart Ehrman says: “The reality is that we don’t have archaeological records for virtually anyone who lived in Jesus’s time and place,”

And of course even if Jesus did leave behind some tangible evidence, it is only the rare artefact that survives for two millennia and is discovered today.

Archaeology research is a slow process. It may take many years after a dig for the structures and artefacts to be analysed, dated and conclusions drawn and published. Nevertheless some interesting discoveries have come to light in the past decade.

What can we expect?

If we can’t expect to find a coin with Jesus’ head on it, what can we expect and what can it show about Jesus?

- Some finds may directly verify or contradict the gospel accounts. These would be rare.

- Some may make some aspect of the gospel accounts more or less plausible.

- Most will illustrate and make more “real” some aspect of first century Jewish life.

There are examples of each of these in the summaries which follow.

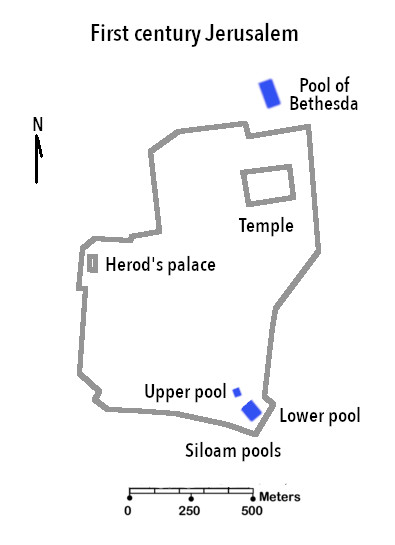

Pools in Jerusalem

There were several pools in ancient Jerusalem, as part of the water supply system, as places for ritual washing (e.g. before pilgrims entered the temple), and some which were believed to have healing properties.

Pool of Siloam

Over the centuries there have been several pools at the lowest point of Jerusalem. In about 1,800 BCE, the Jebusites (Canaanites living in the city of Jebus that was later named Jerusalem) fortified the Gihon Spring, which was outside the city walls and built a small covered channel to provide drinking water for the city and irrigation water for land outside the city walls. Unfortunately, this arrangement allowed attacking armies access to the water, the only reliable water supply in the area.

The Bible (2 Kings 20) records that King Hezekiah, facing the threat of siege by the Assyrian Army about 800 BCE, had a new tunnel dug through solid rock to divert water from the spring to a pool inside the walls. This provided secure water for the city and denied the besieging army a water supply. These works may actually have been commenced a century earlier but finished by Hezekiah. When Jerusalem was re-established after the Babylonian exile, the pool is named as “Siloam” (Nehemiah 3).

This pool apparently fell into disuse, perhaps filled with sediment or covered with rubble. Later in the Byzantine period (4th century) the present day pool (the upper pool) was constructed at the end of Hezekiah’s tunnel.

For many years this Byzantine pool was considered to be the Pool of Siloam where Jesus is reported (in John 9:7-11) to have sent a blind man to wash his eyes, despite the fact that it didn’t fit well with the brief description in John’s gospel. But in 2004, archaeologists uncovered another pool (the lower pool), just down the hill from the Byzantine pool, and this is now considered to be the first century Pool of Siloam.

This pool was built in the first century BCE, and appears to have been used as a mikveh, a pool for ritual washing and purification. One pilgrim route up the hill from Siloam to the temple was unearthed in 2004 and will soon be open to tourists.

The first century pool was large, the size of at least two Olympic pools, maybe more, with steps down to the water on at least three sides. Present excavations have only uncovered the steps on one side of the pool (see main photo above).

It isn’t certain whether Hezekiah’s pool was located at the site of the upper or lower pool. New excavations of the first century pool were announced this year, and may settle this matter. The lower (first century) pool has also been opened to the public for the first time.

Pool of Bethesda

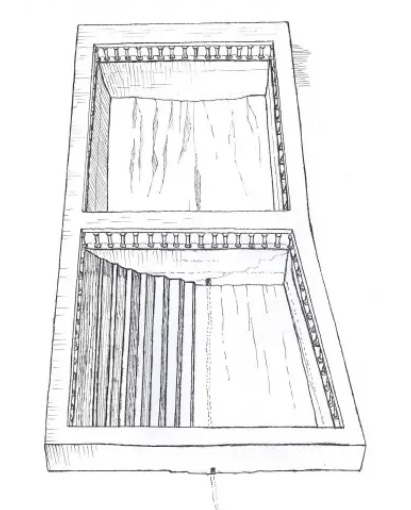

The Pool of Bethesda, where Jesus was reported to have healed a lame man, is described in John 5 as being located near the Sheep Gate and having five porticos or colonnades (more or less verandahs). For a long time this was seen as a fanciful and inaccurate statement (was it constructed as a pentagon?). In any case, the pool had not been discovered and its location was uncertain.

In the 19th century, a pool was discovered in the northeast of Jerusalem and considered likely to be Bethesda because it was located near where the Sheep Gate had been. The 5 porticos remained a mystery, though some guessed the answer.

Excavations in 1964 confirmed this – there were actually two pools, separated by a dam, with porticos on each of the four sides and across the dividing dam, as shown in the diagram, and in the model reconstruction (below).

It is believed there was an ancient pool in this area. A dam was constructed in the 8th century BCE to collect rainwater. This wasn’t a reliable source, but the pool was used for drinking water in the upper city because it was easier to fetch water from here than from the Spring of Gihon or the Siloam pool. It was known as the upper pool, not to be confused with the upper Siloam Pool, and it is mentioned in Isaiah’s account of the Assyrian siege (Isaiah 36).

Probably about 30 BCE a splendid Roman style double pool was constructed by Herod the Great, the site previously having been used for a Roman temple and healing pool. Each pool was roughly square and about the size of two Olympic pools. The pools appear to have been used for bathing and ritual purification (their location was close to the temple) and the waters were believed to have healing properties. Originally, and at the time of Jesus, the pools were outside the city wall, but when Herod Agrippa extended the city walls in about 40 CE, the pools were then inside the walls.

The Bethesda pools were destroyed when the Romans sacked Jerusalem in 70 CE and eventually buried under rubble until rediscovered in the 19th century. As far as I can ascertain, the most recent excavations at Bethesda were a decade ago.

Model of Pool of Bethesda at the time of Jesus.

Galilean synagogues

Jesus is recorded as preaching in synagogues around Galilee (e.g. Mark 1:39), but for many years it wasn’t clear whether there were any synagogues in Galilee in Jesus’ day, except perhaps in homes. But this century several have been found and excavated.

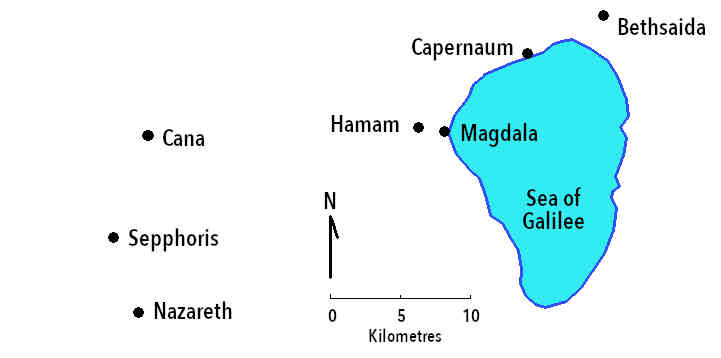

Magdala

Magdala (now called Migdal), reputedly the home of Mary Magdalene in the gospels, is located on the western shore of Lake Galilee. In 2009 archaeologists unearthed the remains of a first century synagogue together with part of the town, including a marketplace, a large villa or public building with mosaics, frescoes and ritual baths, a fishermen’s neighborhood, and a section of a first-century harbor.

The synagogue included a mosaic floor, coloured frescoes, rooms for Torah readings, private study and storage of scrolls, and a bowl for ritual hand washing.

An exciting find was the so-called “Magdala stone, a stone block with a carving of the menorah from the Jerusalem temple, and believed to date from before the Jewish uprising in 67-70 CE. The stone was placed centrally in the synagogue and appears to have been used as reading desk or podium.

Then in 2021, a second syagogue was discovered in Magdala, just 200 metres from the previous discovery. It included a main hall and two other rooms with some of the white plaster walls decorated with colorful designs. Also found were pottery candle holders, molded glass bowls, rings and stone utensils used for purification rituals.

Both syagogues are believed to have been in use from about 50 BCE to 67 CE – which obviously includes Jesus’ lifetime. It is quite possible he visited one of these synagogures.

Hamam

Just a few kilometres west of Magdala, near the small town of Hamam, another synagogue was discovered during a 2007-2012 dig, along with ten residential buildings, two olive-oil presses, thousands of pottery vessels, hundreds of coins and oil lamps and many glass vessels.

This settlement was judged to have been begun in early first century BCE, flourished early first century CE when the synagogue was built, and destroyed in the Bar Kokhba revolt early second century.

Nazareth

Nazareth, where Jesus grew up, was a small village of up to 1,000 people in his day, but is now a city of almost 80,000. Understandably, finding the remains of the first century village is difficult without undermining existing buildings.

This has led some sceptics to argue that Nazareth didn’t exist in Jesus’ day, with the inference that therefore Jesus wasn’t a real historical figure. The logic isn’t sound (clearly Jesus could be real even if the sources were mistaken about where he came from), but this century has seen strong evidence of a first century settlement emerge.

- In excavations in 1997-2007, archaeologists found a winepress, several watchtowers, stone irrigation channels and agricultural terraces, all evidence of farming. Coins and pottery found at the site confirm there was working farm in the first century just a few hundred metres from the village.

The remains of two courtyard houses have been uncovered barely a hundred metres apart. Dateable artefacts indicate they were inhabited in the Roman-period, which included the first century. One house has three pits or cisterns cut from the bedrock for storage, but possibly also used to hide from Roman soldiers during the 66-73 CE uprising. In later centuries, one of these houses was believed to be the boyhood home of Jesus, though there is no way this can be confirmed.

The remains of two courtyard houses have been uncovered barely a hundred metres apart. Dateable artefacts indicate they were inhabited in the Roman-period, which included the first century. One house has three pits or cisterns cut from the bedrock for storage, but possibly also used to hide from Roman soldiers during the 66-73 CE uprising. In later centuries, one of these houses was believed to be the boyhood home of Jesus, though there is no way this can be confirmed.- More underground rock-hewn silos, cisterns, grottos, basins, winepresses, and cellar stores with interconnecting corridors have been found under later Christian churches. These suggest that further residences were located there before being removed to make way for the churches.

- A number of first century graves and rock-cut tombs also indicate a first century settlement.

Archaeologist Ken Dark published the academic book Roman-Period and Byzantine Nazareth and its Hinterland in 2020. Just this year he has produced a shorter book aimed at a more general audience: Archaeology of Jesus’ Nazareth.

Ken Dark has outlined a number of conclusions about first century Nazareth:

- it was religiously conservative – its inhabitants followed Jewish purity laws,

- there was no evidence of Roman residents or of destruction (as occurred in some nearby villages) during the Jewish uprising in 67-70 CE,

- the inhabitants were relatively poor – no expensive or luxury items were found,

- stone quarrying was a significant part of Nazareth life, and it is likely that Jesus and his father worked in stone as well as timber carpenty.

This spate of evidence has made things difficult for the Nazareth sceptics, and they have tended to resort to conspiracy theories and personal accusations to explain why archaeologists disagree with them.

Read more about Nazareth plus photos in Were Bethlehem and Nazareth real places?

Gruesome details about crucifixion

A tomb in Jerusalem escavated in 1968 contained the bones of a young man named Yehohanan, including a heel bone with an iron nail through it, indicating he had been crucified around the time of Jesus. This was the first time ever the bones of a crucified person had been discovered.

This discovery answered some questions about crucifixion:

- It helped define how the Romans carried out crucifixions. It was first thought that the nail penetrated both heelbones, but analysis just this year has shown that Yehohanan was crucified with his legs beside the timber post rather than in front of it as often depicted. (You can read the gruesome details if you want, with sketches.)

- This burial shows that crucified victims could be given a decent burial, though it wasn’t common for crucifixion victim’s bodies to be reclaimed and buried with their community. The gospel stories of Jesus’ burial are disputed by many, but this shows it wasn’t impossible.

- The tomb contained the remains of two generations of a family, at least 17 people and probably many more (the reports I’ve read weren’t clear on this). Most of the bones were in ossuaries – stone boxes where the bones were re-interred a year or so after first being placed in the tomb. This allowed space for further burials. Ossuaries weren’t cheap so were not used by poorer people. This tomb indicates that Yehohanan’s family was wealthy. Despite this, most of the family seemed to have died relatively young (three quarters before the age of 37) and several showed signs of illness, deprivation or violence. Yehohanan’s ossuary had his name on the outside.

- Yehohanan’s right leg tibia had been broken by a sharp blow, a practice used to hasten the death of Jewish victims, as mentioned in the gospels.

Several others skeletons of crucified men have since been discovered. A 2018 study of the bones of a man buried in Italy about the time of Jesus, and excavated in 2007, revealed that he had probably been crucified. And in 2017, an almost complete skeleton unearthed in England was found to have a nail through the heel bone.

What can we learn from all this?

Archaeological discoveries this century have given us new understandings of first century Galilee and Judea. None has thrown any part of the gospels into doubt, and a few have verified accounts in the gospels or at least explained problems that have been raised. As we have seen:

- John’s gospel gives some accurate information about the Pool of Bethesda (and to a lesser extent the Pool of Siloam) that could only be known by someone who visited the sites in the period before they were destroyed in 70 CE. Studies have shown that there are other locations for which John’s Gospel gives accurate descriptions, supporting the view that the gospel is based on a good historical source (see Archaeology and John’s gospel for details on this).

- The discovery of three early first century synagogues in and near Magdala disproves some recent doubts about the gospel record of synagogues in Galilee.

- Archaeology at Nazareth shows that the village was inhabited at the time of Jesus, contrary to some sceptical claims.

- The discovery of the remains of a crucified man in a rich family tomb shows that the gospel accounts of the crucified Jesus’ body being buried in a rock tomb isn’t impossible, even if it was unusual.

None of this proves the gospels are accurate history of course. But if archaeology had undermined the gospel accounts, that would make it harder to believe the gospels are historical. So these facts must logically make it a little easier to believe they contain genuine historical information based on sources that saw the events and knew the locations.

Further reading & watching

The following references contain far more information and visuals than I could include here, and are recommended.

- The Temple and the Pools of Siloam and Bethesda. Craig Keener, YouTube. This 3 minute video is well worth watching to get an appreciation of Jerusalem geography.

- Unearthing the World of Jesus. Ariel Sabar, Smithsonian Magazine, 2016.

- Pool of Siloam excavation update May 2023. Youtube.

- 1st Century Synagogue Part 1. Archaeology. Magdala. YouTube.

- London Archaeologist Believes He May Have Discovered Jesus’ Childhood Home. Ken Dark on YouTube.

- The Excavations at the Bethesda Pool in Jerusalem: Preliminary Report on a Project of Stratigraphic and Structural Analysis: Text, and Illustrations. Shimon Gibson.

Main photo: excavation of the first century Pool of Siloam (BiblePlaces.com).

Sketch of Bethesda in Ref 6b.

Photo of Bethesda model in Wikipedia.

Photo of Magdala stone in Wikipedia.

Photo of remains of Jerusalem house by Israel Antiquities Authority.

The remains of two courtyard houses have been uncovered barely a hundred metres apart. Dateable artefacts indicate they were inhabited in the Roman-period, which included the first century. One house has three pits or cisterns cut from the bedrock for storage, but possibly also used to hide from Roman soldiers during the 66-73 CE uprising. In later centuries, one of these houses was believed to be the boyhood home of Jesus, though there is no way this can be confirmed.

The remains of two courtyard houses have been uncovered barely a hundred metres apart. Dateable artefacts indicate they were inhabited in the Roman-period, which included the first century. One house has three pits or cisterns cut from the bedrock for storage, but possibly also used to hide from Roman soldiers during the 66-73 CE uprising. In later centuries, one of these houses was believed to be the boyhood home of Jesus, though there is no way this can be confirmed.