I reckon too many people, christian and non-christians alike, read the Bible in the wrong way.

So how should an unbeliever approach the Bible if he or she wants to read it honestly, whether to learn from it or to critique it?

Two wrong ways

Let’s get two wrong approaches out of the way first.

It’s God’s perfect word??

Many christians believe that the Bible is without error because it was given by God to the writers. Many non-believers start with that same assumption, often often because they were raised in that form of christianity.

And it isn’t long before they find things in the Bible that they can’t accept as being right, and so they simply reject it all.

But this approach falls short for several reasons:

- It ignores the fact that the Bible is composed of 66 separate writings. Rejecting the idea that Genesis has any historical truth is hardly a good reason to reject the possibility that Acts is historical.

- Even if the books in the Bible were actually written by God, they have been copied, translated and chosen for inclusion by fallible human beings. Perhaps some, or even many, problems can be accounted for by copying errors.

- This approach focuses on a certain dogmatic view of the Bible, and doesn’t approach the Bible on its own terms.

Taking this approach is unlikely to lead to either understanding or a convincing critique of the Bible, though it may lead to a reasonable critique of certain dogmas about the Bible.

Snigger, snigger

Some critics choose to simply mock the Bible, perhaps using derisive (and not very clever or original) words like “sky daddy”, “Jebus”, “bronze age goat herders” and “zombies” to make clear their disdain.

This approach must be kind of fun, I suppose, and it keeps the fans happy, but it actually avoids the hard task of making serious points, and it certainly prevents anyone from approaching the Bible with any integrity. In the end, it is counter-productive because it leaves people wondering if they actually have any worthwhile point to make.

So what is the “right” way?Step 1: Read it

Step 1: Read it

It ought to go without saying that it is difficult to honestly assess or critique something you haven’t even read it. It’s easy to base our “understanding” on pre-conceived views.

I remember as a young christian being taught that Genesis 1-11 was historical truth. I believed it until I read these chapters for myself. Then it became obvious to me that this was “folk tale” – it didn’t read at all like history. All that I had heard and read on the subject by conservative christians suddenly seemed less relevant.

Of course our first reading will be uninformed by expert knowledge, but it gives us a good first impression.

2. Check out facts from the experts

First impressions are important because they allow us to read other people’s views with some knowledge of our own. But unless we have been trained in ancient history and literature of the Middle East, we are likely to miss a lot and get a lot wrong. Expert scholars have immersed themselves in the culture, literature, archaeology and history of Bible times, and it is hubris to think we can ignore their learning and still assess the Bible rightly. Examples abound:

- If we don’t understand genre, we’ll likely interpret texts wrongly. If Job is a philosophical poem, then to interpret it as history would be problematic. We can’t begin to understand Revelation without understanding the genre of apocalyptic literature.

- Likewise we will misunderstand if we interpret some figures of speech as literal truth. Did Jesus really want people poking out their eyes or moving mountainous lumps of rock and dirt around the countryside? Or was he using the familiar figure of speech of hyperbole?

- Understanding culture and language is necessary to help us understand idiom and vernacular. For example, first century rabbis interpreted the Old Testament quite loosely, even fancifully, at times. If we expect, or assume, that every Old Testament reference must be interpreted literally, we are misunderstanding rabbinical methods of interpretation.

- Critics may tell us that Jesus never existed, or maybe even that Nazareth wasn’t a village in Jesus’ day. But while believing or disbelieving that Jesus was the son of God are opinions, the existence of Jesus and Nazareth are historical matters which require good knowledge of the literature, history and geography of that time, and also familiarity with what constitutes good historical evidence.

In these and many other examples, starting with a particular view of Biblical truth and inerrancy will often lead to critiquing passages on grounds which scholarship doesn’t justify.

For example, some christians use fulfilment of Old Testament prophecy as a means of “proving” the divine source of the Bible. Sceptics counter by pointing out that (1) some passages weren’t literally fulfilled, and (2) some of the New Testament “fulfilments” are strained. But neither “side” has taken enough notice of scholarship, which suggests that (1) prophecy was not so much about literal fulfilment as about God’s warnings and encouragement (and was therefore often conditional in its predictions), and (2) it was quite in accord with rabbinical exegesis to interpret prophecies, and even non-prophetic passages, in loose and even fanciful ways.

Of course the experts aren’t always right, and they can have their biases, particularly in the conclusions they draw, so there is a place for being sceptical about the experts. But expert conclusions must surely be the starting point and our major source of information.

3. Don’t see things only through modern eyes

If we are going to read the Bible with understanding, we need to try to see things through the eyes of the writers, readers and hearers. It is so easy to make assumptions that may be true today, but wouldn’t have been true then.

For example, some sceptics argue that the gospel stories about Jesus can’t be true because very few contemporary writers mention him, and surely a miracle-working son of God would have gained more attention. But the scholars tell us that Jesus is actually mentioned by more writers than many other figures who were seen as more important at the time. Of course subsequent history has shown that he has been one of the most influential people who ever lived, but he wasn’t seen as that at the time.

Each of the 66 books that make up our Bible was composed and/or compiled by an author or authors at a particular time for a particular purpose, and tacitly assuming they would have behaved like moderns will surely lead to misunderstanding. They may have had quite different purposes than we realise.

4. Be wary of amateurs with an axe to grind

It is easy for christian or sceptic alike to allow their own biases and preconceived opinions to guide their reading. If they want to reinforce their own views, this is the way to do it (and that can be legitimate) but reading the Bible honestly requires us to read experts on both sides of the important issues.

Some unbelievers are incredibly selective in who they take notice of, sometimes building critical views on one or two writers, often with no relevant credentials, while ignoring the contrary views of the consensus of experts.

5. Be wary of assuming the belief you were brought up in

Ex-christians are often inclined to assume the view of the Bible they were brought up with, or are most familiar with. But if they have left that belief in the Bible behind, they have already decided that is a wrong approach, so how can they assess the Bible honestly if they follow that approach?

It is likely then that other approaches to the Bible might present more of a challenge to their critique.

6. Use the best information you can find to assess or critique

If any of us is arguing with someone, we have to take account of their particular views, no matter how strong or weak they may be. But if we are assessing the Bible for ourselves, we need to take account of the best scholarship. It is easy to critique an ill-informed or naive view, but that hasn’t really been an assessment of the Bible, only of that view.

From information to criticism

Once unbelievers have determined what the experts say about a particular matter, or section of the Bible, they are in a better position to critique the Bible as a source of divine revelation, or not. But there is still the problem of a logical approach.

It is easy to start with our expectations of what God might do, and allow that to drive our assessment. For example, if the Bible was divine revelation, it would be ….. more scientific, more accurate historically, less confusing, able to be interpreted literally, etc …. wouldn’t it?

But those criticisms come from a very shaky basis – what an individual thinks God (if he existed) might do. But what an unbeliever, perhaps an ex-believer, decides God might do is only a valid criticism if God is actually like that, or at least the God a particular believer follows is like that.

There is (I think) a better basis for criticism or assessment.

The starting point should be what we have found, from our own reading and what the experts tell us. Then the question becomes:

Could God have revealed himself this way?

This is a much more complex, and subjective, question to assess. In the end, it is one we all have to face, but it is much harder to insist that others accept our answer.

Two examples

- As I have already mentioned, some sceptics use the alleged failure of Old Testament prophecy as a “proof” that the Old Testament isn’t a divinely inspired book. But if we understand prophecy more as warning and encouragement than as prediction, it becomes a slightly different genre. And if we understand the Bible as an unfolding revelation, these prophecies are not the final word on God’s character. It then becomes much more difficult to say that God couldn’t have used these writings as revelation (whether provisional or “final”) of some aspect of his character. Disbelief on those grounds becomes much more problematic.

- Another source of sceptical criticism is the Canaanite genocide, the apparent command by God to exterminate several people groups. But these commands, and the obedience of the Israelites in ethnic cleansing, sit side-by-side with other commands and other accounts which are not genocidal. The experts say the genocide didn’t happen, and the commands and account are very much propaganda, as was common at the time. Criticising the Bible for including such material is not considering the Bible as it actually is, though criticising christians who believe God did issue such commands is quite fair.

Sauce for the gander?

This post has addressed how unbelievers approach the Bible. But many believers approach it in a similar way. They base their views more on dogma than on historical evidence.

As a christian, I cannot take this course. I think holding a “faith” or “dogma-based” view is legitimate, provided I have good reason to accept that item of faith or dogma in the first place.

But I can find little basis, either within the Bible or in the historical evidence, to justify the view that the Bible is without error and should be interpreted along the lines of modern conservative christianity.

The various books of the Bible are products of their times, and I have no difficulty accepting that God could have revealed himself through these stories, prophecies and letters. It may not be what I would have done if I were God, nor what I would once have expected. But that doesn’t have much weight with me.

Seeing the Bible as the scholars tell us it is has become an important part of my belief, and has actually enhanced my faith in God.

The last word

I think thoughtful discussion of the Bible is of benefit to both believers and sceptics. Unfortunately, it seems to me that too little follows the suggestions I’ve outlined here. The result is that too many believers and sceptics talk past each other. They may feel reinforced in their (dis)belief, but I’m doubtful much light is shed on the Bible, nor is either viewpoint much challenged.

Feedback?

I’d be interested in what any readers think about all this.

Read more

- The New Testament as history. On this website.

- Difficulties with the Bible. On this website.

- Guess What: Prophecies Aren’t Predictions of the Future (You Can Look It Up). Peter Enns

- Was Jesus a copy of pagan gods? On this website.

- 5 Things You’re Reading, When You’re Reading The Bible. Benjamin Corey

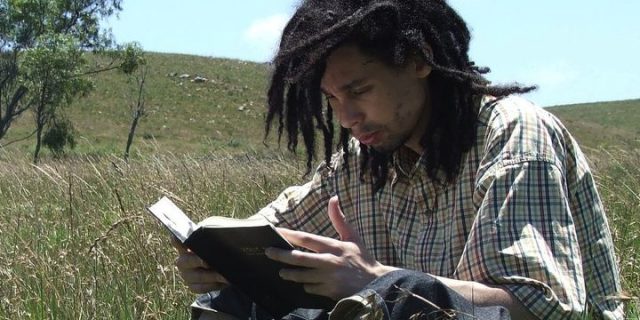

Photo Credit: Rushay via Compfight cc

Very helpful. Thank you.

Thank you, interesting post, maybe just what I need to hear. My husband has lost his faith but is open to reading the Bible with me and perhaps we need to approach reading of it with more openness and less expectation that it is black and white: either all accurate and true historically/literally or none of it is true or useful.

Hi Amy, thanks for the encouragement that this blog has been helpful. I have been and will be praying for you both.

It may be good to start with one or more of the gospels, for they are good stories and are the centre of our faith. We modern westerners (I assume that includes you) can miss some of what is going on, but a good book can help bring the gospels alive and help us to see the excitement.

I suggest either Jesus a very short introduction by Richard Bauckham (a brief overview of Jesus’ life from an eminent historian) or Jesus through Middle Eastern Eyes by Kenneth Bailey (a longer examination of many stories and events in Jesus’ life by someone who lived in the middle east for 60 years).

All the best.