Before we read a book, we will often want to know who wrote it and whether we can trust them to give us accurate information. It is therefore understandable that people might wonder who wrote the 27 books of the New Testament.

Last post I discussed the writings of New Testament scholar Bart Ehrman. One of his books discusses the authorship of the books of the New Testament, and he concludes that quite a few of them (at least a third) are forged, that is, not written by who they claim to be written by.

So I searched the internet to find what other qualified scholars had to say on this matter, and have found that there are few easy answers. There are widely different views on the authorship of some books, with conservative and critical scholars often disagreeing strongly with each other.

What I concluded

I have written a lengthy page on the matter of New Testament authorship (Who wrote the New Testament? Does it matter? and came up with four conclusions.

1. There are reasons to question the traditional authorship of some New Testament books.

Christian writers in the first few centuries almost universally endorse the traditional authors – Matthew, Mark, Luke and John for the gospels, Luke wrote Acts, and Paul, Peter, James, Jude and John wrote the letters and Revelation. There were a few exceptions:

- there were several opinions on the authorship of Hebrews,

- a few writers said a different John wrote some of the books often associated with the apostle John, and

- there were a few books (e.g. 2 Peter, Revelation, 2 & 3 John) that were much argued over, partly because of doubts over authorship, and a few others that just missed out.

So the historical evidence indicates a fair degree of unanimity about authorship, but a few doubts.

Modern scholars use analytical methods to test authorship, for example:

- Setting – Does the book in question address ideas relevant to the time it was written, or a later time?

- Theology – Does the theology of the book match what we know of that author from other writings?

- Style & vocabulary – Is the style (e.g. sentence length, brevity) and vocabulary similar to other works by the same author?

- Disagreements – Do the ideas in the book match other writings by the same author?

- Literacy – Was the author literate enough to write such a book?

Using these criteria throws up a number of anomalies, which some scholars believe are sufficient to identify a different author than the one named.

2. Conservative and critical scholars answer some of these questions differently, and our conclusions will likely depend, at least in part, on which group we side with.

Scholars seem to be divided into two generally clear camps. In the blue corner are the “conservatives”, often christian historians at christian universities who generally believe the modern analysis is insufficient to discount the clear historical evidence. In the red corner are the “critical scholars” who take a more sceptical approach and believe more or less the same as Bart Ehrman, that many books were not written by the traditional authors.

This makes it hard to know what answer is correct, and hard sometimes to find middle ground between the two “camps”. The temptation for us all might be to see the disagreements as christian vs sceptic, and so go with the view we find most congenial and not allow our beliefs to be challenged in any way.

But there are a few lights in that darkness. There are a few scholars that cross boundaries, and we can be more confident in allowing them to guide us.

- There are several christian scholars who would surely be respected for their historical method, but who nevertheless accept most of the traditional authors. Bruce Metzger, who Bart Ehrman describes as a “revered” scholar, and Harold Hoehner would be examples.

- Several christian scholars (e.g. Ben Witherington, Bruce Metzger) express doubts about the authorship of some of the books, predominantly 2 Peter and Jude.

- The late Maurice Casey, certainly a critical scholar and not a christian, seemed comfortable with somewhat conservative views of the authorship of the first three gospels.

3. I think the arguments against traditional authorship often assume more than we can really know, and are therefore less convincing in many cases, but may be right in some.

Obviously I’m no scholar, so the best I can do is to (1) try to judge the consensus of scholars, and (2) try to assess the merits of the arguments.

In most cases, both these considerations seem to favour at least giving the named authorship the benefit of the doubt, and being open to the possibility that anonymous writings may have been correctly identified by tradition.

- The arguments about style, theology, etc, seem to me to rely to much on modern scholars knowing with confidence more about the authors and their purposes than they in fact can know.

- The methods used seem to lack rigour. For example, a scientific experiment would use a control group to test the outcomes, based on clear criteria. But I haven’t seen statistical criteria defined for any of the vocabulary or style conclusions, nor any comparisons made with other writers. It may have been done, but I found no examples. This makes the conclusions subjective at best.

- The critics don’t seem to me to have sufficiently discounted the possibility that some books were written by a group, or in stages, and the most prominent author named, as some scholars think has happened in both Old and New Testaments.

- CS Lewis argued that some biblical critics lack literary judgment and their attempts to recover the origin of a text are often mistaken. He urges greater humility in any attempt to overturn the judgment of people closer to the event.

But a few books must be doubted:

- There are several Johns in New Testament times, and it seems impossible to know which of them may have written, or been a co-author, of John’s gospel, 1, 2 & 3 John and Revelation.

- There are reasonable doubts about the authorship of 2 Peter and Jude.

- I think we may reasonably give the benefit of the doubt to the other books that scholars question, while remaining open to other possibilities.

4. This conclusion seems to be contrary to the doctrine that the words of the Bible were given by God, but makes little difference to those who hold a looser concept of God’s inspiration.

I don’t think any of these doubts changes much. The few books with serious doubts about authorship are generally quite small and seem to add little to christian revelation or belief.

But if a book makes false claims about its author, this raises ethical issues. Can we believe that God inspired a lie?

Thus I think these doubts are a difficulty to any christian who has a view of inspiration that involves God giving the New Testament authors the words they wrote.

But if we hold a looser view of inspiration, as I do, which simply says God used the writings of fallible humans to carry his revelation, then these doubts make little difference. Even if it is true that 2 Peter wasn’t written by the apostle, it is quite possible that the Holy Spirit guided those who finally established the New Testament canon to include it.

I’m still thinking about all this, but that’s where I’ve got to so far.

So who wrote the New Testament?

Check out my more detailed conclusions in Who wrote the New Testament? Does it matter?.

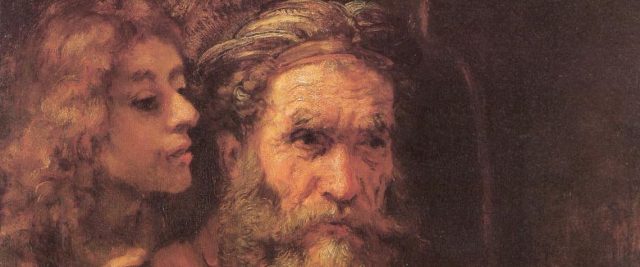

Picture: the gospel writer Matthew, inspired by an angel, by Rembrandt – from Wikipedia, Public Domain.

Good morning unkleE. I just finished reading Constantine’s Bible by David L Dungan. He uses 50 pages of historical references for his 159 page book on how our current Bible came about. I was wondering if you have read it ?

Hi Ken, no I haven’t read it. Most of my research was done on the web. I have read Ehrman’s Forged and a few other books where this topic is addressed in a smaller way, but otherwise websites and papers available online (such as Metzger’s).

How would you summarise that book?

I never judge a book by its author. I judge all books by their content. Come on, if you have even read the bible you will realize that Satan tempted Adam and Jesus using scripture anyway. So even the words attributed to God are used to deceive.

I enjoyed the post, unkleE. When I have time, I’ll check out the (presumably longer) article you wrote on the subject. Hope you have a great weekend!

Hi James, I’m sorry but I’m not sure I’m understanding your point. Are you saying that the “tests” of the modern critics mean very little?

Hi Nate, thanks. Yes the page is longer. It gives the reasoning behind my 4 conclusions plus a table of how I think each book comes out of the assessments.