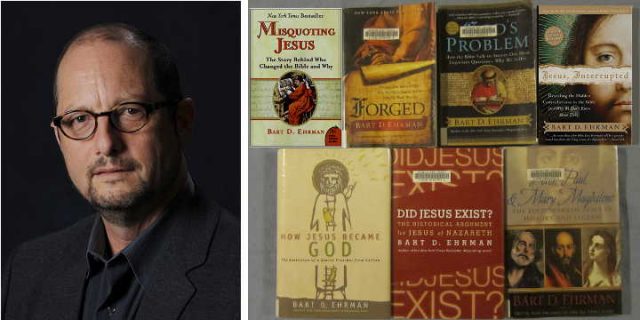

Bart Ehrman is an eminent New Testament scholar, a successful writer and a thorn in the side of conservative christians. I have been reading a few more of his books lately (those shown in the picture above), to see what makes him simultaneously so popular and unpopular.

Some clear themes emerge, and I think they may be of interest to those who take a historical approach to the New Testament. (For newcomers to this blog, I am a non-conservative christian, and Ehrman is an agnostic leaning towards atheism, so you can interpret my comments in that light.)

The life of Bart

Bart was raised Episcopal, and was a committed participant and acolyte. But at about age 15, while at High School, he became a ‘born again christian’, which included believing that the Bible was inspired and inerrant. He was, apparently, a zealous evangelical christian, and attended Moody Bible Institute and Wheaton College, two evangelical bastions. Motivated to understand the Bible better, he went on to study New Testament at Princeton under respected evangelical scholar Bruce Metzger (who he still obviously respects deeply – he describes him as “revered”) and obtained his PhD.

But his graduate studies led him to see the Bible as much more fallible than he had been taught. As a result, he was a liberal christian for about 15 years before finally become an atheist-leaning agnostic. He says his growing New Testament scepticism was not the cause of his disbelief, and the main issue for him was the problem of how a good God could create or allow a world with so much evil and suffering. But I suspect that the uninspiring nature of liberal theology played a part – if Jesus wasn’t really the son of God and didn’t really rise from the dead, what’s the point of following him?

So for years now Bart has been a New Testament professor, the author of many academic and popular books, a sceptic, a speaker and a blogger. In this post I’ll review his approach to several important questions found in a number of his books.

The gospel according to Bart

Ehrman the scholar

Ehrman is an eminent New Testament scholar, and most of his early publications were academic, not for popular consumption, or else aimed at students. I have read none of these, so cannot comment on them except to say that through them he seems to have established a reputation as a fine scholar.

The reliability of the New Testament text

This is one of Bart’s main areas of expertise, so you’d expect his books on this topic to contain good information, and they do. Misquoting Jesus addresses the question of whether the texts we have today are reliable copies of the originals. In those days original documents did not last very long, and so copies were made, and copies of copies, only some of which survive today. With copying comes variation, mostly minor copying errors, but occasionally something more substantial.

For most ancient documents, we have few copies, but for the New Testament we have thousands. This means there are many, many variations across the thousands of copies, but of course the sheer number of copies makes it possible to assess which version of any section of text is most likely the original.

Ehrman explains all this, and the methods scholars use to define the most probable text, and says that most variations are “completely insignificant, immaterial, of no real importance”. But his other conclusions are more controversial.

On the basis of less than a dozen more significant variations, Ehrman says “how radically the text had been altered over the years”. But curiously, he can also agree with Bruce Metger that “the essential Christian beliefs are not affected by textual variants” and he would have “very few points of disagreement” with Metzger about the New Testament text.

More conservative scholars said that Ehrman was exaggerating the problems. Based on his own evidence, it seems to me that Ehrman overstated his conclusions a little. But Michael Kruger suggests Ehrman is emphasising the impact that even small variations may have on the doctrine of Biblical inerrancy.

Forged addresses the question of who wrote the 27 NT books. Ehrman gives the basic information – a third don’t say who their author is, another third are considered by “critical scholars” to be written by someone other than who they say (known as pseudepigrapha) and only the remaining third are generally accepted as being written by the named author. Ehrman argues that writing in someone else’s name was common practice in the ancient world, it was not considered to be acceptable, and should be considered as forgery. In which case, should these books be in the New Testament at all?

But critics say he has claimed far too much. Many agree that if false claims are made, the books should be considered to be unworthy of being included in the scriptures, but they argue that Ehrman’s arguments are weak and inconsistent. For example, differences in writing styles could have been the result of using secretaries and editors – Ehrman says this didn’t happen, others say it did. Conservative critics say Ehrman claims the consensus of “critical scholars” without defining who these are, and thereby ignores many scholars who disagree with him.

I found Forged to be less convincing than other Ehrman books because the arguments seemed more speculative and uncertain. I found that one of the references cited by Ehrman, a paper written by his mentor Bruce Metzger, showed that there were definitely alternative conclusions despite Ehrman’s claim that most scholars supported his conclusions.

Bart Ehrman’s latest book, Jesus before the Gospels, addresses the question of how the stories about Jesus were passed on before they were written down in the gospels. I haven’t read this book, but NT scholar Raphael Rodriguez criticises it for not reflecting the best research on this topic, for Ehrman rarely refers to the extensive research on social memory.

Jesus Interrupted also addresses many of the questions discussed above, and throughout this post, but there is no need to duplicate my discussion.

I will be doing separate posts on the NT authors and memory studies in the near future.

Correcting historical errors

While Ehrman can be seen as a critic of conservative christianity, some of his books argue against the extreme sceptics who say Jesus never existed, or find conspiracies in early christianity and hidden meanings in the NT text.

In Did Jesus Exist?, Ehrman directly addresses the claims of Jesus mythicists and lays out the historical reasons why he, a non-believer, nevertheless is confident Jesus indeed existed as a real person walking the roads of Galilee and living a life more or less as described in the gospels (though Ehrman doesn’t, of course, believe in the miraculous elements).

His argument is twofold. First he points out that the evidence of at least 10 separate sources within the NT is compelling – it just isn’t believable that so many sources written in so many different locations could collude to present a fabrication. This evidence is backed up by the evidence in Tacitus and Josephus, two sources which he says the consensus of scholars accept as confirming the basic facts of Jesus’ life and death.

Secondly, Ehrman examines the claims of the leading mythicists and find some of them to be “howlers”, and even the best of them to be inventions (e.g. Jesus was another dying and rising god legend) or weak and irrelevant (e.g. criticisms of the gospels as historical sources, or the idea that Nazareth didn’t exist at the time of Jesus).

Ehrman received broad scholarly support for his conclusions, and the main criticisms came from mythicists who lack either qualifications or peer recognition, or both. Richard Carrier claimed several errors in the book, but they were generally matters of minor detail and Ehrman had explanations to support his “facts”. The most Carrier achieved was to show that Ehrman may have been careless in his choice of words in a few places.

Peter, Paul and Mary Magdalene considers popular legends around these three Biblical characters,and the historical information we actually have about them. Both legend and fact are important for the historian, for they tell us what people thought important enough to record.

Who was Jesus?

How Jesus Became God addresses a most interesting question – when and how did the early christians, who were Jewish monotheists, come to believe that Jesus was the divine son of God and the second person in the Trinity? Did Jesus say it clearly during his life? Or did it take them decades to come to that belief? Even though Ehrman doesn’t believe that’s who Jesus was (and is), how that belief developed is important for a historian.

Ehrman believes that Jesus didn’t explicitly claim to be divine, but to be the Messiah, a human figure who would rule in the coming kingdom. But his followers’ beliefs changed after they saw visions of him after his death and came to believe he had been resurrected. So this change was very early, before any of the NT was written.

But it gets more complicated. Ehrman argues that the first century Jews believed there were intermediate figures between ordinary humans and God – angels, the Messiah, the son of man, etc. Some of these were divine beings but lesser than God, some were humans who were “exalted” to being divine beings after they died. And he believes Jesus thought of the son of man as a figure yet to come, not himself.

So for Ehrman, the first christians believed Jesus was a man who was exalted after his death to become “a divine being, not God, but ruling with God”. Later, he says, came the belief that Jesus had pre-existed as the divine son of God, as portrayed in John’s gospel.

Larry Hurtado, who has studied this topic more extensively that Erhman, critiques some of Ehrman’s ideas, suggesting that he has ignored some of the evidence he and other have researched. For example, he argues that there is no evidence that anyone ever saw the phrase “son of man” as referring to a separate divine figure, and that Jesus’ usage of the term is seen by all experts on the subject as “self referential”. Hurtado also says Ehrman’s view that Paul saw Jesus as an exalted angel is based on interpretations of several passages that most scholars have rejected. Hurtado says Ehrman is “misinformed” and his conclusions “slanted”.

I have few problems with much of Ehrman’s analysis. It was a long time ago now that I noticed that in the early speeches in Acts, the apostles speak of Jesus becoming Lord rather than being Lord (e.g. Acts 2:36: “God has made this Jesus, whom you crucified, both Lord and Messiah”) and it is only later that they say he was Lord and divine from the beginning (e.g. Philippians 2:6 speaks of Jesus “being in very nature God”). And I find this quite explicable. It was a massive jump from being a monotheist to being a Trinitarian, and good teachers, which I take God and Jesus to be, take their pupils along to new understandings in small steps. So I think it quite natural that the early church took time to come to a mature view on who Jesus was.

But I find Hurtado more convincing on this matter than Ehrman. I also feel Ehrman’s interpretation of passages which seem to speak of Jesus as fully divine (e.g. Philippians 2:6-11, Romans 9:5) is a little forced. As Hurtado says, this book still has plenty of good information in it, though I think Hurtado’s How on Earth Did Jesus Become a God? is more compelling.

Bart has written his views on how we should historically understand Jesus in Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium. I haven’t read that book yet, but he touches on his views in Jesus Interrupted. He, along with many scholars, say Jesus is best understood as an apocalyptic prophet who warned of God’s imminent judgment of Israel, the end of this age, and the setting up of God’s kingdom which the Messiah would rule. But, he says, it never happened.

I have little problem with most of this also. Scholars seem to like to be able to classify Jesus in some way, and apocalyptic prophet (which in his case included being a teacher and healer who demonstrated that evil would be defeated in the future kingdom) probably describes how Jesus would have been seen by his contemporaries.

I just believe he was more than that, and I think, contrary to Ehrman, that he did indeed set up God’s kingdom on earth, and we christians are living in it. For just as Jesus was a different different type of Messiah than the Jews expected, in that he didn’t intend to overthrow the Romans, so I believe his kingdom was a different kind of kingdom than Ehrman thinks.

Overall assessment

I see several common themes in these books.

The personal stories

Bart characteristically begins many chapters with personal stories of his time as a christian or as a university lecturer. I’m only guessing, but I think it may be that he hopes to establish his credentials as an honest inquirer, and also to make the books more personal and therefore more interesting. Whatever, it is very effective and illuminating.

Not anti-christian?

Bart repeatedly says that he’s not anti-christian, he isn’t trying to disturb anyone’s faith, he is just presenting facts that people should know. This seems to be important to him. But his critics argue exactly the opposite, that he is anti-christian and presenting opinions rather than facts.

I think it is best to take him at his word about his intentions. If he is biased (see more below) then his bias should be pointed out without making personal accusations about motives, about which we can only guess.

A consensus of critical scholars?

Bart claims over and over that he isn’t being radical, but is simply presenting the broad conclusions of the majority of “critical scholars”. This claim needs to be tested.

- I don’t remember reading any definition of these “critical scholars”, and critics say they are simply the ones who agree generally with Bart. If this is so, then his claim proves little. But is it the case?

- It is fair to say that some well qualified scholars work from a christian perspective, and so they are unlikely to come to sceptical conclusions. Some teach at institutions that require conformity to a conservative christian doctrinal statement. But it is also fair to say that everyone, including Bart, has their own personal perspective. Instead of making accusations or arbitrarily dismissing some viewpoints, conclusions are judged by the opinions of expert historians of all viewpoints via peer review.

- In the reviews of several of his books, or discussions of the subjects of the books, I have found many scholars who seem to be well respected by their peers who disagree with Bart, either explicitly or implicitly – for example Bruce Metzger, Larry Hurtado, NT Wright, Raphael Rodriguez, Richard Bauckham, Maurice Casey. This in no way indicates Ehrman’s conclusions are wrong, but it does throw doubt on his repeated claims to represent the consensus view of the best scholars.

I conclude that Ehrman overstates the certainty and scholarly support for his conclusions sometimes. Obviously his views are to be respected and assessed on their merits, but in books written for the general public, it seems he claims too much.

Does Bart go too far outside his expertise?

His expertise is generally considered to be the text of the New Testament and the history of early christianity. His earlier books generally were within these areas, but he has been criticised for some of his later books not showing enough familiarity with the area of research under discussion.

I think there is some justification for this criticism, but in his defence, he is a more successful populariser than most scholars, so it is hardly surprising that he will widen his scope to inform the general public. The stronger criticism remains that he doesn’t always present alternative views fairly or completely.

Biased?

So is there a bias in Ehrman’s writings?

I think we have to be careful with accusations of bias. All of us have our opinions, and these naturally colour how we approach questions such as the historical value of the New Testament. I am not immune from bias, neither are christian scholars, and neither, I suggest, is Bart Ehrman. His views on Jesus are coloured by his experience of life and his personal beliefs, just as everyone else’s are. For any scholar, the antidote to bias is following accepted methods that assist in objectivity, and the process of peer review leading to the consensus of scholars.

I disagree with some of Ehrman’s conclusions, not only because I start from a different point to him, but on the basis of the comments of his peers, which support much of what he says but oppose some key conclusions. Bart is clearly entitled and qualified to draw his conclusions, but I think he tends to present them as being factual when they are much less certain, and claim scholarly consensus more than is warranted.

Agent provocateur?

I think it may be fair to see Bart as a stirrer, an agent provocateur, whose popular books overstate the case, but are useful in informing the general public and challenging christians to face up to serious questions about the interpretation of the New Testament.

Few scholars would disagree with Did Jesus exist?, but on most other matters I wouldn’t recommend reading him on his own, but in tandem with a scholar who is recognised as an expert in the subject under discussion.

Next post:

A discussion of who wrote the books of the New Testament, and Ehrmans conclusions in Forged.

References

Bart Ehrman’s books referenced here

- Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium (2001)

- Misquoting Jesus (2005)

- Peter, Paul and Mary Magdalene (2006)

- God’s Problem (2008)

- Jesus Interrupted (2009)

- Forged (2011)

- Did Jesus Exist? (2012)

- How Jesus Became God (2014)

- Jesus Before the Gospels (2016)

Webpages

- Reviews of Forged by conservative scholars Mike Licona and Dan Wallace, and by James McGrath, who is not conservative.

- Larry Hurtado’s book How on Earth Did Jesus Become a God?, and his review of Bart Ehrman’s book.

- Reviews of Misquoting Jesus by Dan Wallace, Michael Kruger, and a thoughtful atheist (though not a scholar), Luke Muehlhauser.

- Raphael Rodriguez’ review of Jesus Before the Gospels (last of 8 blog posts, with links to the first 7).

- Bart reflects on his early christian beliefs.

- Literary Forgeries and Canonical Pseudepigrapha by Bruce Metzger.

On this site

- The reliability of the New Testament text

- Are the gospels historical?

- Does the New Testament contain forgeries, or other books that shouldn’t be there?

- Was Jesus a real person?

- Which historians should we trust?

Bart’s photo by Dan Sears, UNC-Chapel Hill, CC BY 4.0, Wikimedia

I think that’s a very fair review, unkleE — nicely done. It just so happens that I’ve been reading Ehrman lately too. I’ve just finished rereading Misquoting Jesus and Jesus, Interrupted. I’m now reading Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium, which I hadn’t read before. It’s good. I’m glad to get a fuller picture of why Ehrman views Jesus the way he does. I think he makes a compelling case, but like you, I always viewed the “Kingdom of God” as the church. Ehrman may be right in his analysis, but it’s something I’ll have to learn more about before I can say whether or not I agree with him.

I also think things get complicated when we try to parse the gospels themselves and figure out which statements might be more original to Jesus and which might reflect theological evolution over the years. I think the critical approach to these questions is something worth pursuing, but I’m not at a point where I can hold any conclusions about it with much certainty.

Hi Nate, thanks, I’m glad you thought it was fair. I was trying out a few ideas on a theologically aware friend before I wrote it, and he thought I was being a bit tough on Bart, so maybe I moderated a little.

I’m not sure if I equate the kingdom of God with the church. It would be nice if that were so, but I think the church is overall too compromised, and I’m sure the Venn diagram intersects but doesn’t fully overlap. And while I think Jesus envisaged that the community he started would continue, I’m not sure he wanted anything like what we see today!

Finding original statements isn’t as much an issue for me. I think we need to start with what the historians conclude (so Ehrman and others provide a common starting point for people like you and I), but I am happy to trust God to guide the theological evolution in a way that obviously you can’t.

Thanks again, I appreciate your thoughts.