This page in brief

The New Testament we read today is translated from copies of the originals. The copies don’t always agree, so how do we know if the text we read is what was originally written?

Scholars have studied this question intensively, and, while there are many uncertainties, some clear conclusions can be drawn. I have tried to avoid the viewpoints of christian apologists on the one hand and sceptical apologists on the other, and have tried to outline the middle ground of scholarship.

Background facts

The New Testament contains 27 ‘books’ that were originally written as separate documents, probably all in the first century CE. They were only compiled into the volume we call the New Testament several centuries later. Jesus probably spoke in Aramaic, but the Bible was written in Greek.

The copying process

The original documents were most likely written in the period from about 45 CE to 95 CE, in ink on papyrus. Such documents can last for centuries, but if they are well-used, they tend to become worn or lost much sooner. There were no printing presses, so scribes made copies by hand, and copies were made of the copies, and so on. Eventually the originals perished or were lost, along with many of the copies, and the text we have today is constructed from the surviving copies.

It isn’t even certain that there was a definitive “original copy of some books, as it is known that some authors in the ancient world made several drafts of their works, and sometimes earlier drafts found they way into public use. Maurice Casey suggests that the version of Mark’s gospel we have may not have been a finished product because some obvious edits remain to be made.

Surviving copies

More than 5,000 Greek manuscripts of part or all of the New Testament have been discovered. The earliest of these, a few verses from John’s Gospel designated by the Institute for New Testament Research (INTF – see below) as P52, is assessed as being copied in the second century – INTF gives the dates 125-175 CE. This is only 30-80 years after John’s Gospel was written. The earliest complete New Testament manuscripts date from about 350 CE, with complete copies of most books somewhat earlier. In addition, there are around 20,000 manuscripts in Latin and other languages. Most of the document copies we have are, naturally, more recent, from about the 10th to the 15th centuries, when printing replaced manual copying.

This is an unprecedented number of copies, and no other comparable ancient writing comes anywhere near it. The closest is Homer’s Iliad, with almost 2,000 copies, the oldest probably dated several centuries after Homer’s writing. For most classical works, including the historians Tacitus, Josephus, Thucydides, Pliny, Livy, Julius Caesar and Herodotus, only a few hundred manuscripts (or less) survive, and the gaps between the original and the earliest copy are typically hundreds of years. (For a relatively recent attempt to summarise these figures, see The Bibliographical Test Updated, Christian Research Institute, 2013.)

Comparing copies to determine the original text

When a scribe copied a manuscript, mistakes could be made, or, occasionally, the text could be deliberately altered – perhaps to make something clearer, or to ‘correct’ or change the words in the exemplar (the text being copied). The scribe, or another scribe, would generally check his work, and most manuscripts include corrections, some made during copying and others made subsequently and shown in marginal notes. For example, the papyrus P66, which contains most of the Gospel of John, contains over 450 corrections, most by the original scribe, though this is unusual.

Any variations that remained would then be carried through to subsequent copies, except when scribes used more than one exemplar on which to base their copies, in which case variations might not be carried forward beyond the single copy. By comparing manuscripts from different parts of the Roman empire or from different dates, and sometimes identifying “families” of texts, textual scholars can check the accuracy of transmission and try to reconstruct the original text. Other things being equal, greatest weight is generally given to readings in the oldest manuscripts, to the most prevalent variation, and to readings which are considered least likely to have been changed – whether deliberately or by mistake.

The evidence shows that copying was of varying quality, but the checking procedures kept the texts remarkably intact. However since there are such a large number of manuscripts, there are of course many, mostly minor, variations remaining, but also many copies which can be used to ascertain what is probably the original text.

There are a number of standard Greek texts for the New Testament, where the scholars have chosen what they consider to be the most likely original text, though of course there are differences of opinion on this. These variations are generally marked in modern Bibles, with the text considered most likely used, and the alternative shown in a footnote. Different translations may use different Greek texts.

The variations

There are about 138,000 words in the Greek New Testament, but I have found it difficult to get clear consistent information on the number of variations. There is a big difference in the answers given by different ‘experts’, and more than one way to do the calculation. But here is the best information I can find.

Number

Statistics in this section come mainly from Myths about variants by Peter Gurry, chapter 10 in Myths and Mistakes in New Testament Textual Criticism by Elijah Hixson and Peter Gurry.

Scholars estimate there are about 500,000 variant readings in the more than 5,000 manuscripts we have of the Greek New Testament, if we ignore simple and recognisable spelling mistakes. This counts every variation in each word, including the word that is regarded as the best representation of the original in each case. Thus there are very few words which don’t have some variation somewhere among all the manuscripts, and on average there many be 3-4 variants per word.

This sounds like a lot, but of course we have so many variants because we have so many documents. And we can also say that, on average, scribes would make one variant reading for each 400-500 words, which is actually quite accurate. Nevertheless, there are many variants that need to be considered in determining the actual text and its meaning.

When the number of insignificant variants are stripped out (see below for more on this), it is estimated that only about 2-3% of all these variants make any difference to the translation. Bart Ehrman, an expert on textual issues who takes a more sceptical view than most scholars, says:

To be sure, of all the hundreds of thousands of textual changes found among our manuscripts, most of them are completely insignificant, immaterial, of no real importance for anything other than showing that scribes could not spell or keep focused any better than the rest of us.

Types of variations

- The most common form of variation is spelling – minor mistakes by the scribe or the use of local spelling of place names and other words – which rarely make the meaning unclear.

- Gross mistakes – omission or repetition of words – also occur, but are generally quite obvious, and can be discarded.

- Sometimes the word order is changed, which might make a difference in English, but generally makes no difference to the meaning in Greek.

- A scribe may write a word that sounds or looks like the word in the text. Mostly this too is obvious, but sometimes this changes the meaning in a plausible way that makes it difficult to decide which was the original.

- Sometimes it appears that the scribe has added or changed a word to make the meaning clearer, particularly when the text was read out aloud in church meetings (often the only way many illiterate people would know the scriptures).

- Occasionally words are changed or added to reinforce a theological point, or harmonise with other sections of scripture. These cases are relatively rare, but obviously important. A few are discussed further below.

A relatively small number of these variations give different but plausible meanings, and in two cases they add significant passages to what is believed to be the original text.

The significance of the variations

The following discussion focuses on the small number of variations that change the meaning in a clear way.

Three significant additions (and one less so)

Two large passages are generally believed to be later additions to the original text, and are set apart and marked as such in most Bibles. They are John 7:53-8:11, where Jesus intervenes to stop a woman being stoned to death for committing adultery, and Mark 16:9-20, an ending of Mark’s gospel, which otherwise seems to finish abruptly. (Some scholars believe the John passage is a genuine memory from the time of Jesus but not included in the original text of any gospel.)

The words of Luke 22:43-44 (An angel from heaven appeared to him and strengthened him. And being in anguish, he prayed more earnestly, and his sweat was like drops of blood falling to the ground.

) appear to be an addition. They are included in most Bibles, but a footnote explains that they may not be original.

An extra 25 words (in English) appear to have been added to 1 John 5:7-8, apparently to give greater support to the doctrine of the Trinity. This has been known for centuries and most Bibles retain this section only in a footnote.

Changes in meaning

Some significant remaining passages are:

- Mark 1:1 begins with “The beginning of the gospel of Jesus Christ, Son of God”, but several important and old manuscriots omit the words “Son of God”. Since Mark uses these words to describe Jesus elsewhere, the addition of the phrase (if that is what occurred) wouldn’t be contentious. In the end, most New Testament texts include the words, but noting they are uncertain.

- In Mark 1:41, Jesus is approached by a man with a skin disease, who asks to be healed. The majority of texts say Jesus was

moved with compassion

but some texts say Jesus wasangry

. Maurice Casey suggests Mark has translated an Aramaic word wrongly and later scribes corrected this. - In Luke 2:33, the phrase

the child’s father and mother marvelled …

was changed in some manscripts toJoseph and his mother marvelled …

, apparently to avoid any implication that Joseph was Jesus’ biological father. However the original is used in most Bibles today. - During his crucifixion, most texts of Luke 23:34 include Jesus’ words:

Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.

However several early manuscripts don’t have these words. Scholars are split whether they should remain or not. - Manuscript copies of John 1:18 have several slightly different variations of two or three words. In essence, the difference comes down to whether Jesus should be called

son of God

orGod

. This is a significant difference theologically, although both translations presented highly exalted views of Jesus’ status. Modern translations are split between the two meanings. - Romans 5: 1 is generally translated:

we have peace with God through our Lord Jesus Christ

but a number of manuscripts have:let us have peace with God …

- Hebrews 2:9 is generally translated

so that by the grace of God he might taste death for everyone

, but some manuscripts have one word different in the Greek, which would then translate as… apart from God he might taste death ….

.

Christian teachings affected by these variations

The impact of these variations is arguable, and amount to:

- We lose a much-loved story of Jesus in John 8. No teaching is affected, and christians are likely to continue to use the story anyway.

- Likewise the important quote about Jesus forgiving his executors is thrown into some doubt, but will likely still be used by most christians.

- The loss of the ending in Mark changes little, except removing the reference to snake-handling and drinking poison.

- Several verses which might once have taught the Trinity or Jesus’ divinity are removed or diluted. There is support for these doctrines elsewhere in the New Testament, but the case is slightly weakened.

- Jesus may have been angry in one more situation than previously thought.

- The meaning of a few passages is more difficult to know for sure.

Were changes made to promote orthodox theology?

The claim is sometimes made that in many cases scribes made changes deliberately to promote a particular theological belief, and that therefore the Bible we have has been corrupted by one branch of christian belief. This claim is denied or minimised by others. It turns out that the truth appears to be somewhere in the middle.

Method

While variations can easily be identified, and the history of the changes made to the text can sometimes be reconstructed, it isn’t so easy to establish a motivation. If a particular scribe consistently made changes in the same theological direction, we can conclude that the changes were intentional, but if we only have one such change, and other opportunities were not taken up, we can conclude that the change was probably not theologically motivated.

Some examples

Robert Marcello (in Myths about orthodox corruption, chapter 11 in Myths and Mistakes in New Testament Textual Criticism edited by Elijah Hixson and Peter Gurry) gives two examples where this method indicates a systematic change to the exemplar text, and two examples where theological bias has been claimed but cannot be sustained.

- The Codex Bezae’s text of Acts shows many variations from other manuscripts, and it has been shown that 40% of these variations are more critical of Judaism.

- The P72 text for 1-2 Peter and Jude shows consistent variations that strengthen the divinity of Jesus

- Some texts of Matthew 24:36 have Jesus showing ignorance about the time of his return, while others downplay this, but this bias isn’t consistent across the text, and so it seems the variation wasn’t doctrinally motivated.

- Likewise the variations in John1:18 (discussed above) are sometimes claime dto be due to theological bias, but again, there are good arguments that other explanations should be preferred.

So it seems that there are some places where the original text was changed to preserve orthodox theology, but this isn’t common. The christian apologists are wrong to minimise it and the sceptics equally wrong to overstate it.

Conclusion

The large number of variations occur because of the extremely large number of manuscript copies. Thus scholars are in a good position to determine the most probable text in most cases. For most ancient documents, we do not have this luxury.

It is hard to see that the uncertainties are significant, and most scholars affirm this. The late Bruce Metzger said: I don’t know of any doctrine that is in jeopardy

. The only doctrine I think is threatened by these variations is the christian view of the Bible itself.

Most christians believe the Bible is inspired by God, and many believe it is without any error in the original manuscripts. However these textual differences throw some doubt on these doctrines, for the following reasons:

- We don’t have the original manuscripts, and as we have seen, there may never have been a definitive final “original” manuscript for some books. So the doctrines don’t apply to the Bible we read.

- If God wanted us to read an inspired, inerrant Bible, it is argued he would surely have kept the copying without error as well, so that his words were available to us. However, “inspiration” is a term that means different things to different people, and the idea that inspiration by God must imply no, or minimal, copying errors isn’t a view held by all christians.

- Some of the variations appear to have been made because the scribes recognised errors of fact, doctrine or grammar in the exemplar they were copying from.

So textual variations may lead us to conclude that the New Testament we read is not ‘inerrant’, but the variations are not major, they have minimal impact on our historical knowledge and they should not disturb anyone’s faith in Jesus. Perhaps christians need to reassess their view of the Bible God has given us.

I personally find all this information interesting and exciting, for I believe they help me understand God better.

Sources and references

While I have read works by scholars who might be seen as christian apologists who minimise the problems (e.g. FF Bruce in The New Testament Documents: Are they reliable?), and others who might be seen as over-critical and thus over-state the problems (e.g. Bart Ehrman in Misquoting Jesus), I have tried to mostly reflect the middle ground. I have therefore used as my main source Myths and Mistakes in New Testament Textual Criticism by Elijah Hixson and Peter Gurry (2019), which aims to avoid both the extremes.

The final authority on the New Testament text is the Instituts für Neutestamentliche Textforschung (INTF), or Institute for New Testament Research. However since I cannot read German, I have to use the INTF information second-hand.

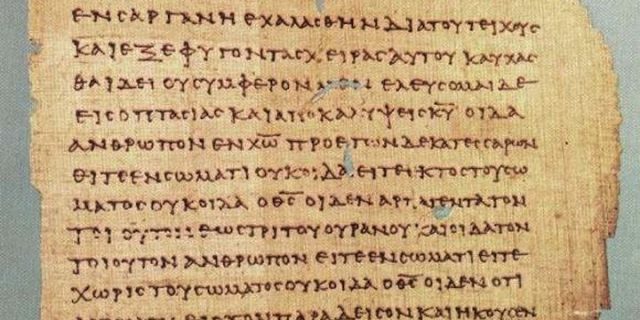

Photo: A section of Papyrus 46 showing part of the book 1 Corinthians. P46 is dated about 200 CE and contains many of the New Testament epistles. (Wikipedia).

This page extensively re-written December 2019.

Feedback on this page

Comment on this topic or leave a note on the Guest book to let me know you’ve visited.